Amphibians & Reptiles of the Adirondacks:

Wood Frog (Lithobates sylvaticus)

The Wood Frog (Lithobates sylvaticus) is a small to medium-sized frog that spends most of its time in forests, but breeds primarily in ephemeral pools, permanent ponds, or freshwater wetlands.

The Wood Frog is currently assigned to the Lithobates genus (American Water Frogs). Other frogs native to the Adirondack Mountains also assigned to this genus include American Bullfrog, Mink Frog, Northern Leopard Frog, Pickerel Frog, and Green Frog. The species name is derived from the Greek word "lith," meaning stone, and "bates," meaning one that walks or haunts The species name (sylvaticus) is Latin for "amidst the trees" – a reference to the habitats where it spends most of its time.

As is the case for a number of other plant and animal species, the Green Frog's taxonomic status is the subject of ongoing debate in the scientific community.

- At one time, the Wood Frog was assigned to the genus Rana. In 2006, as part of a larger revision, the Wood Frog was removed from Rana and assigned to Lithobates. However, there is still disagreement among specialists over whether the revision was justified and whether Lithobates should be recognized as a genus or as a subgenus within Rana.

- The debate remains unresolved with some authorities (i.e. the Integrated Taxonomic Information System and the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles) identifying the species as Lithobates sylvaticus and others (i.e. AmphibiaWeb) continuing to list the species as Rana clamitans.

At one time, three subspecies of Wood Frogs were recognized. The most common form was classified as Rana sylvatica sylvatica. In the 1940s, however, herpetologists began suggesting that subspecific status should be withdrawn. Currently, there are no recognized subspecies.

Wood Frog: Identification

Adult Wood Frogs are small to medium-sized frogs, ranging in length from 1½ to 3 inches. Coloring is variable, ranging from brown, tan, rust, pinkish, to nearly black. The most useful clue to the Wood Frog's identity is its distinctive dark mask which begins as a thin line at the nose and then widens to include the eardrums. There is a white, cream, or gold stripe along the upper lip. The head is pointed.

This species also has prominent dorsolateral foldsDorsolateral Folds: Ridges of raised skin running down the sides of a frog's back. Many members of the Ranidae family have such folds. (ridges) extending from just behind the eyes almost to the end of the body. The hind legs are long and generally have three or four dark cross bars. The belly is white.

Wood Frogs are sexually dimorphic. Adults males are smaller than females. Females are also typically more brightly colored. In addition, the webs between the hind toes are concave in females and convex in males. During breeding season, male Wood Frogs have a swollen thumb.

Wood Frog tadpoles are usually dark gray to brown and have a faint light-colored stripe along the upper jaw. They can reach a length of up to two inches. There are no distinct markings on the body.

Similar Species: Several other species native to the Adirondack Mountains are somewhat similar in appearance to the Wood Frog.

- Like Wood Frogs, Green Frogs are quite variable in color. Green Frogs also have dorsolateral foldsDorsolateral Folds: Ridges of raised skin running down the sides of a frog's back. Many members of the Ranidae family have such folds.. However, Green Frogs lack the Wood Frog's dark eye mask; and the Green Frog's tympanium (eardrum) is much larger in relation to the eye.

- Northern Leopard Frogs are also green or brown, with prominent dorsolateral foldsDorsolateral Folds: Ridges of raised skin running down the sides of a frog's back. Many members of the Ranidae family have such folds.. However, they lack the dark eye mask of the Wood Frog. Moreover, the Northern Leopard Frog's upper body and limbs are covered with dark, rounded, light-edged spots that the Wood Frog lacks. Northern Leopard Frogs are also somewhat larger than Wood Frogs.

- Pickerel Frogs are similar to Wood Frogs in size. This species also has prominent dorsolateral foldsDorsolateral Folds: Ridges of raised skin running down the sides of a frog's back. Many members of the Ranidae family have such folds. However, Pickerel Frogs have distinctive rectangular spots on their backs, which Wood Frogs lack. In addition, Pickerel Frogs lack the Wood Frog's dark mask.

Wood Frog: Behavior

During their short breeding season, Wood Frogs can be recognized by their distinctive advertisement calls: a series of short, hoarse calls often described as a soft, ducklike cackling. Wood Frogs are said to be the earliest of our frogs to begin calling in the spring, generally when air temperatures reach about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. At any given breeding site, Wood Frog calls generally coincide with the more melodious sounds of the Spring Peeper.

According to a chart provided in Gibbs et al (2007), male Wood Frogs begin calling in New York State starting in early March in the southern counties, with late breeding populations calling in mid-April. In the northern counties, including those comprising the Adirondack Park, early calling begins on 9 April, with late calling extending to 25 May. The dates in the chart are based on over 10,000 reports of vocalizing frogs in the New York State Herp Atlas in 1990-1999.

The activity pattern of Wood Frogs varies with the season.

- During winter, Wood Frogs hibernate in shallow burrows, beneath forest debris, loose soil, or decaying logs. Most individuals reportedly enter hibernation by the beginning of October. Their burrows are usually not below the freeze line. However, Wood Frogs are able to survive long periods of subfreezing temperatures by producing large amounts of glucose that acts like antifreeze.

- As temperatures warm, the dormant Wood Frogs begin to thaw out, emerge from hibernation, and migrate to their breeding ponds. This is the time when peak activity occurs. They are active both diurnally Diurnal: Active during the day, followed by a period of inactivity or sleeping during the night. Nocturnal animals are active primarily at night, while animals that are active in the twilight hours (dawn and dusk) are crepuscular. and nocturnallyNocturnal: Animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. Nocturnal animals often have highly developed senses of hearing and smell, and specially adapted eyesight to help them get around in the dark. during this time, at least when the weather is warm. On days when the temperature remains under 53 degrees, most activity is restricted to daylight hours.

- After reproduction, Wood Frogs disperse to the surrounding woodland. They spend the summer months in woodlands or forested swamps, leaving their summer habitats to overwinter in neighboring uplands, often in sites adjacent to breeding pools.

Wood Frog: Diet

Wood Frog tadpoles consume algae, diatoms, and decaying plant and animal material. They also eat the eggs and larvae of amphibians, such as salamanders.

Like most frogs, adult Wood Frogs are carnivores. They reportedly are sit-and-wait predators. Their feeding strike, triggered by prey movement, consists of a body lunge to make contact the with prey with the tip of the tongue, in contrast to some other frog species (such as the Green Frog) which engulfs its prey by its fleshy tongue.

The Wood Frog's prey includes ants, beetles, spiders, crickets, moth larvae, and flies. Earthworms, slugs, and snails are also on the Wood Frog menu. Feeding reportedly does not occur during the brief breeding season.

Wood Frog: Reproduction

Wood Frogs are "explosive" breeders, meaning that females lay their eggs over a very few days. This synchronized breeding may be a strategy for reducing cannibalism among the tadpoles, since they are all about the same size and unlikely to eat one another. The short duration of the breeding season may also be linked to the fact that many Wood Frogs breed in temporary pools, which have the advantage of lacking predatory fish, but the disadvantage of often drying up quickly.

Wood Frog breeding sites, in addition to vernal pools and ponds, include permanent woodland ponds, beaver ponds, roadside ditches, and unused canals. Males do not defend territories. They float on the surface, advertising their presence with their distinctive duck-like quacks and attempting to mate with any willing females, as well as other males, salamanders, or even sticks.

Females lay their eggs communally, creating large egg masses in one or two parts of the breeding site. Egg masses are usually attached to submerged vegetation. Females generally leave the breeding site immediately after laying their eggs, while males may linger up to two weeks. Eggs hatch in two to four weeks, depending on water temperature.

The tadpoles transform into adults within about 67 days. Juveniles are miniatures of adult Wood Frogs. Many will congregate under litter near the shore before dispersing, although most (up to 70% or more) will be lost to predation.

Wood Frog: Distribution

Wood Frogs are broadly distributed over North America and are said to be the most widespread North American amphibian species. Their range includes Labrador and northern Quebec southward to Georgia, north through the Great Lakes region, Minnesota, northeastern North Dakota, and across Canada to the Yukon and northern Alaska. .

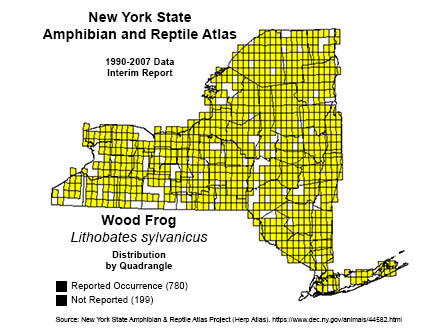

Within New York State, the Wood Frog is fairly common. It has been reported throughout the state. This species is widely distributed within the Adirondack Park Blue Line, although (based on iNaturalist observations) it appears to be somewhat less commonly seen than the Green Frog.

The Wood Frog is of low conservation concern. Predation is a major source of mortality. Tadpoles and egg masses are prey for a variety of aquatic predators, including salamanders, Eastern Newts, and leeches. When in their breeding ponds, adult Wood Frogs can fall victim to turtles, herons, American Minks, and Raccoons. On land, Wood Frogs may be predated by snakes, foxes, coyotes, and larger birds.

Wood Frog: Habitat

Wood Frogs are terrestrial frogs which spend most of the year in forests. Their preference is for mature, deciduous forests, although they can also thrive in mixed forests and some wetlands, including bogs. During breeding season, they are found in or near standing bodies of water, both temporary or permanent.

In the Adirondacks, Wood Frogs breed in several wetland ecological communities, including:

It is easiest to find Wood Frogs in breeding season, when their duck-like quacking alerts passers-by to their presence. Look for them around the edges of temporary or permanent water bodies or floating among aquatic vegetation with the tops of their heads exposed. Like other frogs, Wood Frogs tend to be wary of intruders and will abruptly cease calling and dive beneath the surface of the water if disturbed.

List of Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles

References

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project. Species of Toads and Frogs Found in New York. Wood Frog Distribution Map. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

iNaturalist. American Water Frogs. Genus Lithobates, Retrieved 8 April 2022.

iNaturalist. Wood Frog. Lithobates sylvaticus. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Wood Frog. Lithobates sylvaticus. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Frogs and Toads. Order Anura. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Frogs and Toads of New York. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Lithobates sylvaticus. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 48-49, 53-54, 70-71. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Pine Barrens Vernal Pond. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Shallow Emergent Marsh. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Vernal Pool. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

Virginia Herpetological Society. Wood Frog. Lithobates Sylvania. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

Bernard S. Mart-of, William M. Palmer, Joseph R. Riley, and Jack Dermis. Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas & Virginia. (University of North Carolina Press, 1980). p. 136. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

Carroll B. Knox, “Wood Frog” in Malcolm L. Hunter Jr., John Albright, and Jane Ar buckle, Eds. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Maine. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station. Bulletin 838 (1992), pp. 86-91. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Amphibian. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Wood Frog. Rana Sylvania. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

C. Kenneth Dode Jr. Frogs of the United States and Canada (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), pp. 637-669. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Albert Haze Wright and Anna Allen Wright. Handbook Of Frogs And Toads of the United States and Canada (Comstock Publishing Company, Inc., 1949), pp. pp. 540-544. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Third Edition (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1991), p. 341, Plate 48. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

James P. Gibbs, Alvin R. Breisch, Peter K. Ducey, Glenn Johnson, John L. Behler, Richard C. Bothner. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New York State. Identification, Natural History, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. pp. 38-46, 109-110, 147-150.

James M. Ryan. Adirondack Wildlife. A Field Guide (University of New Hampshire Press, 2008), pp. 102-103.

Arthur C. Hulse. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Cornell University Press, 2001), pp. 179-184, Plates 63 and 64. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

James H. Harding and David A Mifsud. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. Revised Edition (University of Michigan Press, 2017), pp.155-160.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution (University Press of New England, 2001), pp. 43-44, 396-399, 423-426. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Deborah Rudis. Forest habitat for Reptiles & Amphibians of the Northeast (US Department of Agriculture. Forest Service, 1981), pp. 244-246. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

Lang Elliott, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. The Frogs and Toads of North America: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009), pp.198-201. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

John L. Behler and F. Wayne King. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Alfred A. Knopf, 1970), pp.392-382, Plates 211, 212, 214, 216. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

Thomas F. Tyning. A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles (Little, Brown and Company, 1990), pp. 86-95. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Mary C. Dickerson. The Frog Book: North American Toads and Frogs, with a Study of the Habits and Life Histories of Those of the Northeastern States (Doubleday, Page and Company, 1906), pp. 205-211. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Ontario Nature. Reptiles and Amphibians. Wood Frog. Lithobates sylvaticus. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

James P. Gibbs and Alvin R. Breisch, “Climate Warming and Calling Phenology of Frogs near Ithaca, New York, 1900-1999,” Conservation Biology, Volume 15, Number 4 (August 2001), pp. 1175-1178. Retrieved 10 April 2022.