Amphibians & Reptiles of the Adirondacks:

Eastern Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens)

The Eastern Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens) is a common salamander of the Adirondack Park. It has a complex life cycle, including an aquatic adult stage and a terrestrial stage when it is known as the Red Eft.

The Eastern Newt is part of the Salamandridae (Salamander) family. It is assigned to the Notophthalmus genus, which is comprised of three species. The only species in the northeast is the Eastern Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens).

- The genus name is from the Greek words "noto" ("mark") and "ophthalmus" (eye), which may be a reference to the eye spots found on the back and sides.

- The species name (viridescens) is Latin for "slightly green" – a reference to the greenish color of most adult Eastern Newts.

- The Eastern Newt is the state amphibian of New Hampshire.

Some authorities recognize four subspecies: Red-spotted Newt (N. v. viridescens), Broken-striped Newt (N. v. dorsalis); Central Newt (N. v. louisianensis); and Peninsula Newt (N. v. piaropicola). Ours is the Red-spotted Newt. Both the Integrated Taxonomic Information System and Amphibian Species of the World state that these subspecies are no longer recognized.

Eastern Newt: Identification

The Eastern Newt has a complex life cycle.

- The newt begins its life as an egg, deposited singly in submerged vegetation of a pond.

- The egg hatches within three to five weeks into a brownish-green larva, which uses gills to breathe and lives in water. Larvae do not leave the pond environment where they were hatched. The length of the larval period varies, from about two to five or so months.

- The juvenile stage is terrestrial and begins when the larva loses its gills, develops lungs to breathe air, transforming into a Red Eft in late summer. This stage lasts two to seven years. During this stage, the Red Eft may wander far from the location where it spent its larval stage.

- A second metamorphosis occurs when the eft transforms into an adult, which remains in or near a pond for the rest of its life. The adults who live in permanent waterbodies are nearly fully aquatic.

The timing and nature of these stages are quite variable. Although most populations have the four stages described above (aquatic egg, larva, terrestrial juvenile, and aquatic adult), environmental factors, as well as densities, can influence the timing.

Adult Eastern Newts retain the ability to survive on land. In fact, the adults of some populations may spend much of their time on land, leaving their ponds in summer and not returning until the following spring. This pattern is seen among populations where the breeding pools are shallow or seasonal, with adults migrating out of ponds in summer or fall, overwintering on land, and returning to their pond the following spring to breed.

Juvenile and adult Eastern Newts are quite different in appearance. Juvenile Eastern Newts – usually referred to as Red Efts – are smaller than adults, about one to three inches long. Red Efts, as the name implies, have bright orange or orange-red skin with two rows of dark-rimmed yellowish or orange spots on each side of the back. The bright orange coloration is designed to advertise the eft's toxicity to potential predators. The skin is rough. The tail is thin and bony.

Adult Eastern Newts are three to five inches long. The tail is finned and comprises about half of the total length. Adults are two-toned. The upperside is usually olive green or brownish with many small black dots and two rows of red or orange spots on the back. The spots may be outlined in black. The throat, belly, and underside of the limbs are yellow. The skin of adult Eastern Newts is soft and smooth. Breeding males develop black patches inside the thigh and on the hind toe tips.

Similar Species: The Spring Salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) also occurs in the Adirondack Park, although it is less commonly seen than the Eastern Newt. Spring Salamanders have a background color that varies from salmon to brown or reddish, but they lack the rows of distinct, dark-bordered spots of juvenile Eastern Newts (Red Efts).

Eastern Newt: Behavior

Adult Eastern Newts reportedly are active throughout the year, although activity levels probably depend on the severity of the winter. Adults are active throughout the day, foraging as they move about on pond bottoms. Eastern Newts are said to be most active in rainy weather.

Red Eft activity levels are also influenced by weather. Movement and foraging activity correlate closely with rainy weather. The efts move about on the forest floor only when the surface is wet, emerging during heavy showers. They remain active and above ground as long as the surface leaves are wet and disappear as the leaf litter dries. Red Eft activity is also affected by temperature. They are rarely active when the temperatures sink below 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

Eastern Newt: Diet

Eastern Newts are carnivoresCarnivore: Animals that feed on other animals; obligate carnivores (such as members of the cat family) rely entirely on animal flesh, while facultative carnivores supplement their diets with non-animal foods. By contrast, herbivores feed exclusively on plants, although some may supplement their diets with small amounts of insects or other animals. A third category – omnivores -- are animals that eat both plant- and animal-derived food.; they carnivorous during all their life history stages. They are opportunistic feeders, who consume whatever is palatable and available at the time.

- Aquatic larvae are generalist feeders that consume prey in direct proportion to their availability. Eastern Newt larvae feed on insects and their larvae, particularly mayfly, caddisfly, midge, and mosquito larvae. Newly-hatched larvae feed, usually at night, on small invertebrates.

- The terrestrial Red Eft feeds on earthworms and arthropods found within leaf litter. Their menu includes mites, fly larvae, worms, land snails, and slugs. Most of their prey are found in the upper leaf litter layer, soil surface, or low vegetation. Red Efts sometimes are found congregating around decaying mushrooms, apparently to take advantage of the abundant prey attracted to the mushrooms.

- Aquatic adults are also opportunistic predators which will eat any palatable prey they can swallow whole. They feed on aquatic insects, worms, small crustaceans, mollusks, spiders, and the eggs and larvae of other amphibians. They help keep mosquito populations in check by feeding on their larvae. They forage both on the surface of the water and the bottom of their ponds. They reportedly locate prey by both visual and chemical cues.

Eastern Newt: Reproduction

The timing and duration of the Eastern Newt's breeding cycle vary with latitude and climate. Red Efts migrate from terrestrial sites to ponds and streams and become reproductively mature. Those adult Eastern Newts that have overwintered on land return to the breeding ponds, usually migrating on rainy days or nights.

Although Eastern Newt courtship can occur in either late autumn or spring, the female lays her eggs only in spring, with most egg laying occurring in April and May. After elaborate courtship displays, mating occurs with the female picking up the spermatophoreSpermatophore: A capsule or mass containing spermatozoa created by males of various animal species, especially salamanders and arthropods. Spermatophores are composed of a cap containing the spermatozoa on top of a clear, gelatinous platform which fastens the spermatophore to a substrate. deposited by the male. Female Eastern Newts lay up to 300 or 350 eggs, deposited singly (or more rarely in small clusters) on the leaves of aquatic vegetation or other objects on the bottom of the pond or stream. The female wraps each egg in a folded leaf or in other debris on the pond floor.

Eastern Newt: Distribution

The Eastern Newt is one of the most widely distributed salamanders in North America. Eastern Newts are found throughout the eastern United States, from the Canadian maritime provinces west to the Great Lakes and south to Florida, Texas, Alabama, and Georgia.

The Eastern Newt is listed by the IUCN as a species of least concern; its population is considered to be stable. The population may have benefited from European colonization, because the species adapted readily to farm ponds. Increasing beaver populations have also benefitted the Eastern Newt, by creating and maintaining ponds.

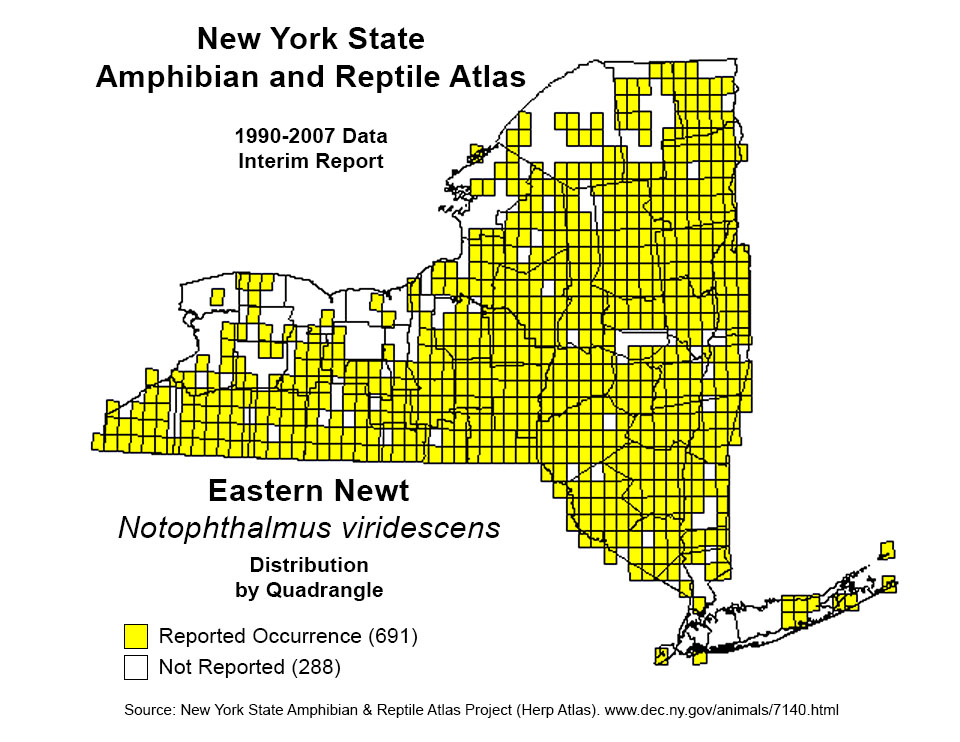

In New York State, the Eastern Newt is fairly widely distributed. These creatures are found throughout the state wherever suitable habitat occurs. Data from the New York Herp Atlas Project indicate that the Eastern Newt is absent from the St. Lawrence Plain, the coastal lowlands of western Long Island, and the Great Lakes Plain. Within the Adirondack Park, Eastern Newts are found in all twelve counties with areas that fall within the Blue Line. However, the species is largely absent from the western Adirondack foothills and sable highlands in the northern and northwest part of the Park.

Material from iNaturalist generally confirms findings from the Herp Atlas. Eastern Newts are by far the most frequently observed salamander in the Adirondack Park. The geographical distribution of iNaturalist sightings within the Park shows that this species is seen most frequently in the central and eastern parts of the Park and is largely absent from the western periphery.

Eastern Newts can live for twelve to fifteen years. Mortality is highest during the larval period. Both juvenile and adult Eastern Newts also fall prey to a variety of predators, despite the toxic skin secretions used to deter them. Reptiles known to prey on Eastern Newts include Common Garter Snakes, Snapping Turtles, and Painted Turtles. The Eastern Newt's main mammalian predator is the Raccoon. The Eastern Newt is also collected for the commercial pet trade, although the impact on its population is not known. In New York State, possession or harvest of native salamanders, including Eastern Newts, is prohibited.

Eastern Newt: Habitat

Adult Eastern Newts inhabit small bodies of fresh water, particularly water with abundant submerged vegetation, including ponds, lakes, deep emergent marshes, and slow-moving rivers. Eastern Newts prefer ponds with dense, submerged vegetation or relatively undisturbed streams, but can also be found in swamps and ditches. Within the Adirondacks, they can be found in a variety of wetland ecological communities, including marsh headwater streams and vernal pools.

During the juvenile Red Eft stage, this amphibian is found on moist forest floors, typically under leaf litter, brush piles, logs, and stumps. Red Efts occur in forests of any type, but seem to prefer deciduous and mixed forests. They are largely absent from grasslands and other open areas.

Look for adult Eastern Newts in beaver ponds or man-made bodies of water, such as the farm pond at John Brown Farm. The brightly colored Red Efts are usually found on the forest floor on moist days particularly during and after heavy showers on days when the temperature is above 50 degrees. In early spring, Red Efts are observed more frequently near the base of trees and stumps. In late summer and early fall, they sometimes cluster around decaying mushrooms.

List of Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles

References

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Eastern (Red-Spotted) Newt. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project. Species of Salamanders Found in New York. Red-spotted Newt. Notophthalmus viridescens. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Nature Explorer. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Reptile and Amphibian Hunting Seasons. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Eastern North American Newts. Genus Notophthalmus. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

iNaturalist. Eastern Newt. Notophthalmus viridescens. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Notophthalmus viridescens. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Salamanders (Order Caudata). Retrieved 12 January 2025.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wildlife Exposure Factors Handbook. Office of Research and Development. EPA/600/R-93/187 (December 1993). pp. 2-429 - 2-442. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Notophthalmus viridescens Retrieved 13 March 2020.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. SSAR North American Species Names Database. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

Amphibian Species of the World 6.0. Notophthalmus Rafinesque. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

Amphibian Species of the World 6.0. Notophthalmus viridescens. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Notophthalmus viridescens. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp.24-25, 70-71. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Marsh Headwater Stream. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Vernal Pool. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

The Nature Conservancy. Laurentian-Acadian Freshwater Marsh. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

Virginia Herpetological Society. Red-spotted Newt. Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Eastern Newt. Notophthalmus viridescens. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), pp. 28-29, 98-100.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 160-165, 214-216.

James P. Gibbs, Alvin R. Breisch, Peter K. Ducey, Glenn Johnson, John L. Behler, Richard C. Bothner. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New York State. Identification, Natural History, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 38-46, 75-78, Plate 9.

James M. Ryan. Adirondack Wildlife. A Field Guide (University of New Hampshire Press, 2008), pp. 97-98, Plate 16.

Arthur C. Hulse. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Cornell University Press, 2001), pp. 66-76. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

James H. Harding and David A Mifsud. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. Revised Edition (University of Michigan Press, 2017), pp. 47-52.

Bernard S. Martof. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia (University of North Carolina Press, 1980), pp. 47-48. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution (University Press of New England, 2001), pp. 31-32, 396-399, 423-426. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John L. Behler and F. Wayne King. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), pp. 275-278, Plates 26, 27, 29, 30.

Thomas F. Tyning. A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles (Little, Brown and Company, 1990), pp. 110-119. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

James W. Petranka. Salamanders of the United States and Canada (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998), pp. 451-462, Plates 159-162. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

Sherman C. Bishop. Handbook of Salamanders: The Salamanders of the United States, of Canada, and of Lower California (Cornell University Press, 1994), pp. 99-103.

Ontario Nature. Reptiles and Amphibians. Red-spotted Newt. Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

Mark C. MacNamara, "Food Habits of Terrestrial Adult Migrants and Immature Red Efts of the Red-Spotted Newt Notophthalmus Viridescens," Herpetologica, Volume 33, Number 1 (March 1977), pp. 127-132. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

Thomas M. Burton, "Population Estimates, Feeding Habits and Nutrient and Energy Relationships of Notophthalmus v. viridescens, in Mirror Lake, New Hampshire," Copeia, Volume 1977, Number 1 (March 16, 1977), pp. 139-143. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

John Thornton Wood and Ollie King Goodwin, "Observations on the Abundance, Food, and Feeding Behavior of the Newt, Notophthalmus Viridescens Viridescens (Rafinesque), in Virginia," Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, Volume 70, Number 1 (June 1954), pp. 27-30. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

Stuart H. Hurlbert, "The Breeding Migrations and Interhabitat Wandering of the Vermilion-Spotted Newt Notophthalmus viridescens (Rafinesque)," Ecological Monographs, Volume 39, Number 4 (Autumn 1969), pp. 465-488. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

William R. Healy, "Terrestrial Activity and Home Range in Efts of Notophthalmus viridescens," The American Midland Naturalist, Volume 93, Number 1 (January 1975), pp. 131-138. Retrieved 3 April 2020.