Trees of the Adirondacks:

Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum)

The Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) is a large, slow-growing, deciduous tree which flourishes in well-drained soil in the Adirondack Mountains. It is a member of the Soapberry Family. The Sugar Maple is one of about twenty species in the genius Acer which occur in North America. This species has a life span of 200-300 years, with some specimens in old-growth stands persisting to nearly 400 years.

The Sugar Maple is one of the most important trees in the eastern United States and Canada, both economically and ecologically. It is the dominant tree in the northern hardwood forest, along with American Beech.

Sugar Maples are also known as Hard Maple, Rock Maple, Head Maple, Sugartree, and Bird's-eye Maple. The Sugar Maple is the state tree of New York. It is also the national tree of Canada, as represented by the maple leaf on its flag.

Identification of Sugar Maple

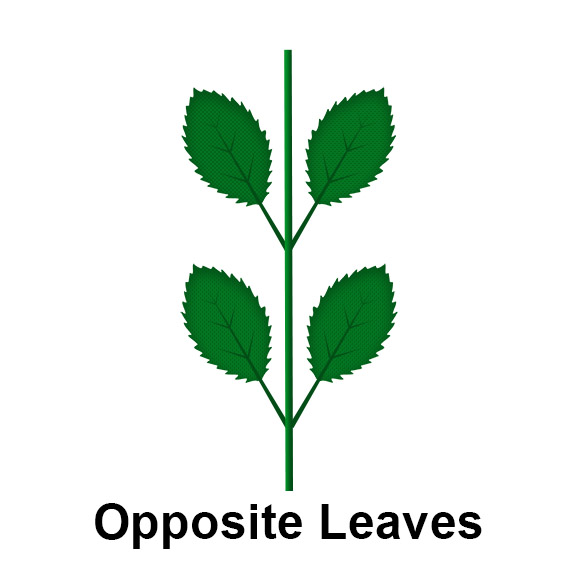

The mature Sugar Maple is a large tree, growing 50-70 feet tall, with a straight, single trunk. The branches are opposite, meaning that they emerge in pairs, opposite one another. Forest-grown Sugar Maples are generally free from branches on the lower third to two-thirds of the tree, with a narrow, rounded crown. Sugar Maple that grow in the open are oval in shape, with upswept lower branches and straight upper branches.

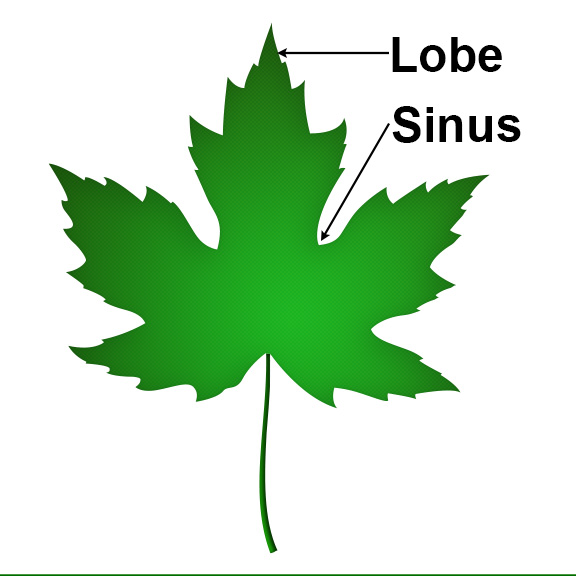

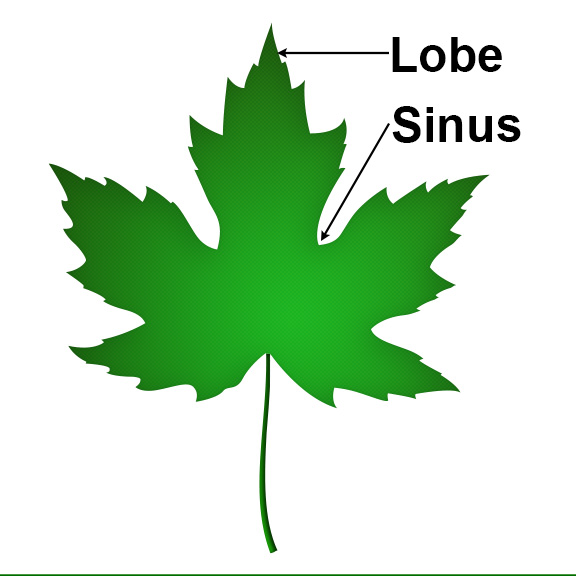

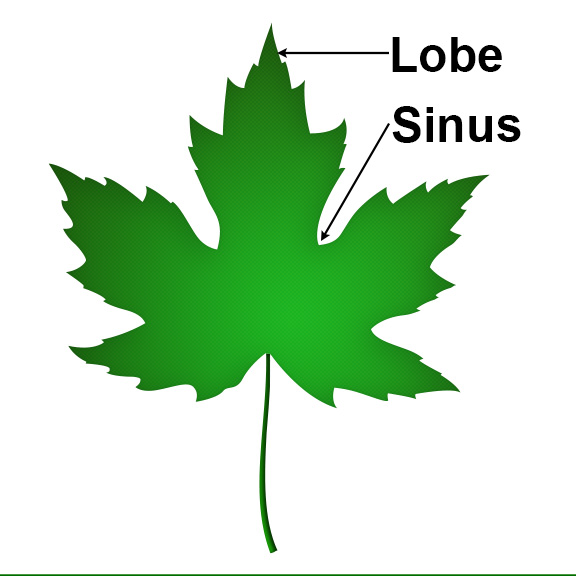

Like other maples, Sugar Maples have opposite Opposite Leaves: Leaves occurring in pairs at a node, with one leaf on either side of the stem., lobed leaves. The leaves of the Sugar Maple usually have five squarish, shallow lobes. Each of the largest three lobes

Opposite Leaves: Leaves occurring in pairs at a node, with one leaf on either side of the stem., lobed leaves. The leaves of the Sugar Maple usually have five squarish, shallow lobes. Each of the largest three lobes Lobe: A projection from an edge of a plant structure (such as a leaf), larger than a tooth. Lobed leaves are leaves with distinct protrusions, either rounded or pointed. has one to several sharp-pointed tips. There is a moderately deep U-shaped notch (sinus

Lobe: A projection from an edge of a plant structure (such as a leaf), larger than a tooth. Lobed leaves are leaves with distinct protrusions, either rounded or pointed. has one to several sharp-pointed tips. There is a moderately deep U-shaped notch (sinus Sinus: In leaves with lobes, the indented area between two lobes.) between the lobes. The upper surface of a Sugar Maple leaf is green in the summer; the lower surface is pale green to whitish. Sugar Maple leaves turn red, yellow, or orange in autumn, contributing to the brilliant palette of colors seen in September and early October in the Adirondacks.

Sinus: In leaves with lobes, the indented area between two lobes.) between the lobes. The upper surface of a Sugar Maple leaf is green in the summer; the lower surface is pale green to whitish. Sugar Maple leaves turn red, yellow, or orange in autumn, contributing to the brilliant palette of colors seen in September and early October in the Adirondacks.

The Sugar Maple flowers in mid- to late-spring, producing tiny greenish yellow flowers with five sepals. In the Adirondack Mountains, this tree usually flowers in mid-May with leaf expansion.

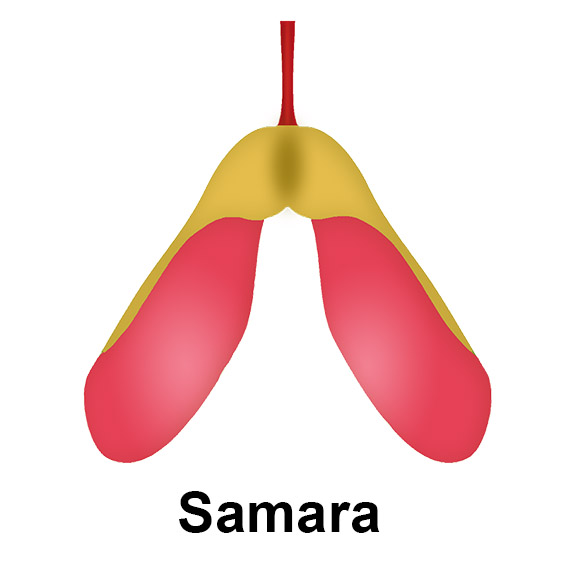

The fruit of Sugar Maple is a pair of winged seeds (called a samara Samara: A type of dry fruit where one seed is surrounded by papery tissue that helps carry the seed away from the tree as the wind blows. ). The winged seeds are green, turning reddish tan. The seeds drop in late summer.

Samara: A type of dry fruit where one seed is surrounded by papery tissue that helps carry the seed away from the tree as the wind blows. ). The winged seeds are green, turning reddish tan. The seeds drop in late summer.

The twigs of the Sugar Maple are glossy and reddish brown. The buds are brown and sharp; the buds are slender and pointed down. The bark of the Sugar Maple is smooth and gray when the tree is young, becoming irregularly furrowed, scaly, and dark gray on older trees.

Keys to differentiating the Sugar Maple from other maples include its leaves, bark, growth habit, and habitat.

- The leaves of the Sugar Maple lack the irregularly and usually double-toothed

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge. marginsThe structure of the leaf's edge. of the Red Maple. The dips between the lobes

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge. marginsThe structure of the leaf's edge. of the Red Maple. The dips between the lobes Lobe: A projection from an edge of a plant structure (such as a leaf), larger than a tooth. Lobed leaves are leaves with distinct protrusions, either rounded or pointed. of the Sugar Maple are u-shaped, while the indentations between the lobes of the Red Maple are pointy, forming a sharp "v." In addition, Red Maple trees are more tolerant of wet soil. A large, single-trunked maple tree growing near a marsh or other wetland is more likely to be a Red Maple.

Lobe: A projection from an edge of a plant structure (such as a leaf), larger than a tooth. Lobed leaves are leaves with distinct protrusions, either rounded or pointed. of the Sugar Maple are u-shaped, while the indentations between the lobes of the Red Maple are pointy, forming a sharp "v." In addition, Red Maple trees are more tolerant of wet soil. A large, single-trunked maple tree growing near a marsh or other wetland is more likely to be a Red Maple. - The Striped Maple is a small understory tree, often divided into several branches from near the base. Its bark has distinctive narrow, white vertical stripes. In addition, its leaves are uniformly and finely double-toothed

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge..

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge.. - The Mountain Maple is another small understory tree. Its leaves are coarsely toothed.

Historical Uses of Sugar Maple

The Sugar Maple was the premier source of sweetener, along with honey, for both Native Americans and early European settlers.

- Native American groups – including the Algonquin, Cherokee, Dakota, and Iroquois – used maple sap to make syrup and sugar.

- The Micmac also used the bark to make a beverage.

- The Ojibwa allowed the sap to sour to make vinegar, which was mixed with maple sugar to cook sweet and sour meat.

- The Potawatomi used maple sugar instead of salt to season all cooking.

The Cherokee used the wood for lumber and to make furniture. The Malecite used the wood to make paddles, torch handles, and oars. The Ojibwa used the wood to make bowls and other cooking tools.

Native American tribes also used the Sugar Maple for medicinal purposes. For example, the Iroquois used maple sap for sore eyes and a compound infusion of the bark as drops for blindness. It was also used as a blood purifier and dermatological aid. The Mohegans used the inner bark as a cough remedy.

Current Uses of Sugar Maple

The Sugar Maple is currently one of the most valuable hardwood trees in the Northeast. Its wood has a wide variety of uses, including furniture, paneling, flooring, interior trim and veneer. Sugar Maple wood is also used for gun stocks, tool handles, plywood dies, cutting blocks, wooden ware, novelty products, sporting goods, bowling pins, and musical instruments. The wood is especially suited for bowling alleys.

Some trees develop special grain patterns, including birdseye maple (with dots suggesting the eyes of birds) and curly and fiddleback maple (with wavy annual rings). Such variations in grain are highly prized in cabinet making. Wood from the Sugar Maple is also a very good fuel, giving off a lot of heat and forming very hot embers. The ashes of the wood are rich in alkali and yield large quantities of potash.

In addition, the Sugar Maple – with sap which has twice the sugar content of other maple species – is the mainstay of commercial syrup production. Production of maple syrup is a multi-million-dollar industry in the U.S. and Canada. Canada, primarily Quebec, produces over 70% of the world's maple syrup. The remainder is produced in the US, where maple syrup production in 2021 totaled 3.4 million gallons. The US value of production in 2020 was $132 million. Vermont is the largest US maple producer, producing 45% of US maple syrup in 2021. New York State is the second largest producer, with 19%.

Sugaring season begins in early spring, starting in February or early March. Nights below freezing and days at higher than 5°C are needed to ensure good sap flow. Each tree yields between 5 and 60 gallons of sap, depending on the health of the tree and the weather.

- Early in the spring, when the maple trees are still dormant, temperatures rise above freezing during the day. As a result, positive pressure develops in the tree, causing the sap to flow out of the tree through a half-inch wide tap hole which has been drilled about 4.5 feet above the ground.

- When the temperature drops back below freezing at night, suction develops, drawing water into the tree through the roots and replenishing the sap in the tree. This allows the sap to flow again during the next warm period.

- This cycle of warm and cool periods is essential for sap flow.

The maple sap is then boiled to produce maple syrup. Fresh sap flowing out of the maple tree usually contains around 2% sugar. Finished maple syrup is 66-67% sugar. To create maple syrup from maple sap, it is necessary to increase the sugar concentration of sap. Many gallons of water need to be removed. Usually, about 40 gallons of sap are required to produce one gallon of finished syrup, depending on the sugar content of the sap, which in turn depends on the health and age of the tree and the time of the season.

Wildlife Value of Sugar Maple

The Sugar Maple is of significant value for Adirondack wildlife. It provides a food source for mammals and insects and is a key component of the breeding habitat for a wide variety of birds.

Sugar Maple is a food source for several wildlife species. White-tailed Deer browse the twigs and foliage. In New York, the twigs and foliage of maple species are reported to comprise 25 to 50% of the White-tailed's diet. Maple species are listed by the state's Department of Environmental Conservation as among the preferred or best-liked winter deer woods, although deer preferences reportedly vary significantly depending on the maple species.

Another mammal said to rely heavily on Sugar Maples is the Porcupine. Sugar Maples are among the ten species of trees that provide much of the Porcupine's winter diet. This mammals eats the bark and can girdle the upper stem, with maple species comprising an estimated 25-50% of its diet.

Other mammals that consume maple species include Moose and Snowshoe Hares, which browse on the twigs and foliage. Red Squirrels, Gray Squirrels, Eastern Chipmunks, and flying squirrels feed on its seeds, buds, twigs, and leaves.

Sugar Maple is also important for several insect species. The flowers appear to be wind-pollinated, but the early-produced pollen is important for Apis mellifera (honeybees) and other insects. In addition, the Sugar Maple is a caterpillar host for the Cecropia Silkmoth and the Rosy Maple Moth.

Sugar Maples are also important for birds that live in the Adirondacks, both year-round residents and summer migrants who travel to our area to breed.

- Upland gamebirds that feed on the buds, twigs, and seeds include the Ruffed Grouse and Wild Turkey.

- Songbirds that consume the seeds, buds, and flowers of maple species include Purple Finch, American Goldfinch, and Red-breasted Nuthatch. Seeds, buds, and flowers from maple species reportedly contribute 25 to 50% of the Evening Grosbeak's diet. Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers use Sugar Maples as a source of sap.

- A number of birds build nests in Sugar Maples, including American Redstart, Black-capped Chickadee, Evening Grosbeak, Least Flycatcher, Philadelphia Vireo.

- For several species – Mourning Warbler, Pileated Woodpecker, Brown Creeper, Hermit Thrush, and Hairy Woodpecker – the Sugar Maple is one of the preferred trees for foraging for insects.

- Twigs from Sugar Maple trees are sometimes used by Chimney Swifts as nest-building material.

A lengthy list of bird species breed in the northern hardwood forest and mixed woods forests associated with Sugar Maples. The list includes:

Blackburnian Warbler

Black-throated Blue Warbler

Black-throated Green Warbler

Blue-headed Vireo

Brown Creeper

Hermit Thrush

Indigo Bunting

Least Flycatcher

Merlin

Mourning Warbler

Nashville Warbler

Northern Parula

Pileated Woodpecker

Red-eyed Vireo

Rose-breasted Grosbeak

Ruby-throated Hummingbird

Scarlet Tanager

Veery

White-breasted Nuthatch

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker

Distribution of Sugar Maple

Sugar Maples are restricted to regions with cool, moist climates. This species is widespread and abundant in the eastern and mid-western United States, into southern Canada. Sugar Maple are found throughout New England and the mid-Atlantic states. This species grows from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick westward to Ontario and Manitoba, North Dakota and South Dakota, southward into eastern Kansas into Oklahoma, and southward in the east through New England to Georgia.

Sugar Maple is present in most New York State counties. This species can be found in all counties in the Adirondack Park, although vouchered plant specimens have not been provided for Clinton, Hamilton, and Herkimer counties.

Habitat of Sugar Maple

The Sugar Maple is one of the most shade-tolerant species in the Adirondacks. Its seedlings will survive on the forest floor for years, growing very slowly until the death of a large tree or some other disturbance opens up the canopy. The seedlings will then begin growing rapidly, eventually reaching crown level. This species is generally regarded as a climax species in northern hardwood forests.

Sugar Maple grows in a wide variety of soils, but does best on deep, fertile, well-drained soils. It is rarely found in swamps. This species does not grow well on soil that is too poorly drained or too shallow. On these marginal sites, it will probably be out-competed by other species such as Red Maple or Yellow Birch.

Ecological communities in the Adirondack Park where Sugar Maples are found include:

- Acidic Talus Slope Woodland

- Beech-Maple Mesic Forest

- Calcareous Cliff Community

- Calcareous Talus Slope Woodland

- Floodplain Forest

- Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Limestone Woodland

- Maple-Basswood Rich Mesic Forest

- Northern White Cedar Rocky Summit

- Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Riverside Ice Meadow

- Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Other hardwoods found here include Red Maples and Yellow Birch. A few Eastern Hemlocks and Red Spruce trees may also be found.

- In the understory of the Beech-Maple Mesic forest, look for characteristic shrubs/small trees such as Hobblebush, Striped Maple, and Alternate-leaved Dogwood.

- Characteristic wildflowers include Canada Mayflower, Common Wood Sorrel, Starflower, Partridgeberry, Foamflower, Whorled Wood Aster, Indian Cucumber-root, Jack-in-the-Pulpit, and Wild Sarsaparilla, as well as spring ephemerals such as Trout Lily.

- Ferns that flourish in this habitat include Hay-scented Fern, Intermediate Wood Fern, Spinulose Woodfern, and Christmas Fern.

Outlook for Adirondack Sugar Maples

The future of Sugar Maples in the Adirondack Park is uncertain. In the 1980s, Sugar Maples appeared to be in a serious state of decline over a wide variety of locations in both Canada and the northeast US. Characteristics of the decline include branch die back, reduced growth, and, in some cases, unusually high levels of mortality.

Growing concern over the Sugar Maple's future led to the creation of the North American Maple Project (NAMP) in the late eighties, with the goal of evaluating and monitoring the health of Sugar Maples, based on assessments of crown conditions. The results, while not definitive, suggested that temporary and reversible stressors, such as insect damage, were the main factors and that air pollution was not causing region-wide maple decline.

More recent research is less reassuring. Sugar Maple declines reportedly are continuing in our area. For instance, a 2015 analysis of growth rings from hundreds of trees across the Adirondack Mountains revealed a decline in the growth rate for a majority of Sugar Maple trees after 1970.

The causes of this decline are unclear. Some researchers have linked the changes to acid rain, noting that Sugar Maples appear to be highly vulnerable to the loss of calcium in the soil caused by the nitric and sulphuric acid in acid rain. Others point to the warmer temperatures associated with climate change. Most specialists concur that Sugar Maple decline is the result of a combination of factors, each of which plays a part in weakening the tree.

Adirondack Tree List

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), pp. 7-16, 41, 42, 43, 51-64, 170-173, 240, 248.

E. H. Ketchledge. Forests and Trees of the Adirondack High Peaks Region (Adirondack Mountain Club, 1996), pp. 135-138.

Edwin H. Ketledge, "The Maples of New York," New York State Conservationist, Volume 16, Number 5 (April-May 1962), pp. 31-32. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Acer saccharum. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Sugar Maple. Acer saccharum Marshall. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. Silvics of North America. Sugar Maple. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Acer saccharum. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. Northeast Maple Syrup Production. 15 June 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. United States Maple Syrup Production. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. New York Ranked Second in 2021 Maple Syrup Production.11 June 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service. Crop Production. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

United States Department of Agriculture. NRCS National Plant Data Center & the Biota of North America Program. Plant Guide. Sugar Maple. Acer saccharum Marsh. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Acer Saccharum. Sugar Maple. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

Stan Tekiela. Trees of New York: Field Guide (Adventure Publications, Inc., 2006), pp. 152-153.

Michael Wojtech. Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast (University Press of New England, 2011), pp. 101-103.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Winter Deer Foods. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 66, 105-106, 107-108, 110, 119-120, 122, 123-124. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Acidic Talus Slope Woodland. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Beech-Maple Mesic Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Calcareous Cliff Community. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Calcareous Talus Slope Woodland. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Floodplain Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Limestone Woodland. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Maple-Basswood Rich Mesic Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Northern White Cedar Rocky Summit. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Riverside Ice Meadow. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 4. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Porcupine. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Sugar Maple. Acer Saccharum. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Native Plant Database. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

University of Wisconsin. Trees of Wisconsin. Acer saccharum. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

Online Encyclopedia of Life. Acer saccharum. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

Plants for a Future. Database. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), p. 352.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Revised and Updated (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 130-131.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. American Redstart, Blackburnian Warbler, Black-capped Chickadee, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Blue-headed Vireo, Brown Creeper, Evening Grosbeak, Hermit Thrush, Indigo Bunting, Least Flycatcher, Merlin, Mourning Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Northern Parula, Philadelphia Vireo, Pileated Woodpecker, Red-eyed Vireo, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Scarlet Tanager, Veery, White-breasted Nuthatch. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. American Redstart, Blackburnian Warbler, Black-capped Chickadee, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Blue-headed Vireo, Brown Creeper, Chimney Swift, Evening Grosbeak, Hermit Thrush, Indigo Bunting, Least Flycatcher, Merlin, Mourning Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Northern Parula, Philadelphia Vireo, Pileated Woodpecker, Red-eyed Vireo, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Scarlet Tanager, Veery, White-breasted Nuthatch. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Eastern Trees (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), pp. 54-55, 206-207.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958,1972), pp. 6-7, 97-98, 120-121.

John Kricher. A Field Guide to Eastern Forests. North America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), pp. 61, 72-75, 126-127.

Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, and Richard Spellenberg. Trees of Eastern North America (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp. 618-619.

C. Frank Brockman. Trees of North America (New York: St. Martin's Press), pp. 210-211.

Keith Rushforth and Charles Hollis. Field Guide to the Trees of North America (Washington, D.C., National Geographic, 2006), p. 201.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Trees (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), Plates 258, 374, 592, pp. 379-380.

Allen J. Coombes. Trees (New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc., 1992), p. 101.

Gary Wade, et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380, p. 5. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169. Retrieved 22 January 2017, p. 6.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Sugar Maple. Acer saccharum Marsh. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (New York: Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 339-340.

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Stackpole Books, 1992), pp. 128-132.

Peter V. Minorsky, "The Decline of Sugar Maples (Acer saccharum)," Plant Physiology, October 2003, Volume 133, Number 2, pp. 441-442. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

Geoff Wilson, "Scientists Challenged by Sugar Maple Decline," Outside Story, 5 September 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

Tim Wilmott, "The North American Maple Project," Farming: The Journal of Northeast Agriculture, January 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

"New Study: Adirondack Sugar Maples In Decline," Adirondack Almanack, 21 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Daniel A. Bishop, et al., "Regional Growth Decline of Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) and its Potential Causes," Ecosphere (21 October 2015). Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Trees of the Adirondack Mountains