Trees of the Adirondacks:

Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera)

The Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) is a small to medium-sized, fast-growing deciduous tree usually found in mixed wood forests in the northern US and Canada, including the Adirondack Mountains. This tree – a close relative of the Yellow Birch (which also grows in our part of the Adirondacks) – is a member of the Birch family. The Paper Birch is short-lived and rarely lives more than 140 years.

The common name derives from the distinctive white bark, which peels off in paper-like layers. This tree is also known as White Birch, Silver Birch, Paperbark Birch, and Canoe Birch. The latter name reflects the use of its bark by native Americans to make canoes.

Identification of the Paper Birch

Paper Birch trees feature a distinctive white bark. The bark of young Paper Birch trees is brownish, but begins to turn white when the tree is about a decade old. The white bark develops paper-like layers. Beneath the loose paper, the tree's inner bark is creamy to pinkish or orangish white. The tree may have dark triangular markings (or chevrons) where the branches have died and fallen off.

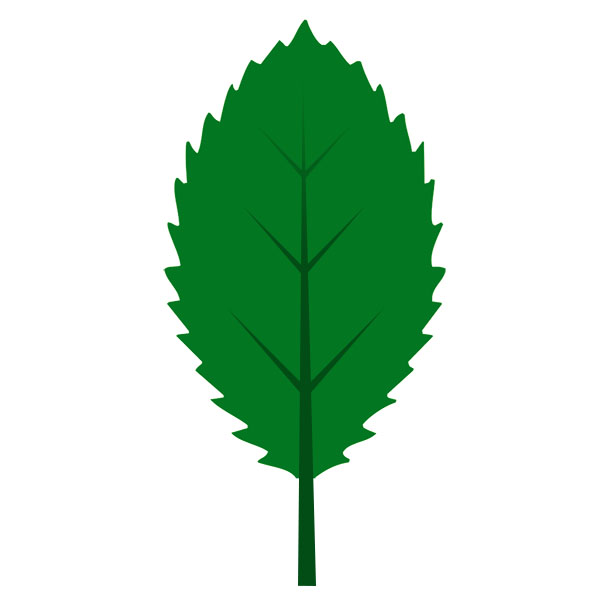

The leaves of Paper Birch trees are green in summer, turning yellow in fall. The alternate Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem. leaves are 2 to 5 inches long and one to three inches wide. They are roughly oval in shape, with tapering tips and edges which are double-toothed

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem. leaves are 2 to 5 inches long and one to three inches wide. They are roughly oval in shape, with tapering tips and edges which are double-toothed Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge. Single-toothed leaves have only a single set of teeth. Double-toothed leaves have teeth with each tooth having smaller serrations on it..

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge. Single-toothed leaves have only a single set of teeth. Double-toothed leaves have teeth with each tooth having smaller serrations on it..

The tiny flowers, borne on catkins, appear in April or May, before or at the same time as the leaves emerge. The yellowish male flowers stand on long, dropping catkins near the twig tip. The green or red female flowers blossom on short, upright catkins father back on the same twig.

The Paper Birch tree's distinctive peeling bark is the main clue to distinguishing it from other deciduous trees in the Adirondacks. The main difficulty is differentiating Paper Birch from Yellow Birch.

- Both Paper Birch and Yellow Birch feature peeling bark. The Paper Birch has bright white bark, the underside of which is a pinkish color. When it peels, the strips are fairly wide, and thick. Yellow Birch bark, by contrast, is more bronze in color; and the bark of the Yellow Birch tends to peel off in thin papery ringlets. This distinction is less helpful in older specimens, when the bark has darkened with age.

- The scent of the stem is another identifier. Scrape a short section of the twig of the birch in question with your fingernail and give it a sniff. If it smells like wintergreen, you have a Yellow Birch.

Uses of the Paper Birch

Paper Birch is used primarily for specialty products such as ice cream sticks, toothpicks, bobbins, clothespins, spools, broom handles, and toys. The bark is also used by crafters to create decorative items. The handsome foliage and showy white bark make the trees attractive for landscaping.

Paper Birch can be tapped in the spring to obtain sap from which syrup, wine, beer, or medicinal tonics can be made. Birch syrup is produced commercially in Alaska and Canada. Sap flow season for birch trees begins when the sap flow in Sugar Maples is coming to an end, allowing sugarmakers to use their existing equipment to produce another valuable crop of birch syrup at the close of maple season. Birch syrup contains lower sugar concentrations than that derived from Sugar Maple and is more acidic. Birch syrup has a caramel-like taste and is used in sauces and glazes.

Paper Birch trees were used by a wide variety of native American tribes in many different ways. Many groups used the plant for medicinal purposes. It was used as a remedy for a wide variety of ailments, including burns, rashes, stomach cramps, dysentery, teething, colds, and coughs. Paper Birch was also widely used as a food. Several native American groups used the sap to make syrup. Others made a tea substitute with the root bark.

The tree had a wide variety of uses as a building material. Paper Birch was used to make canoes and as a building material for walls and roofing. The bark was also widely used to construct containers and waterproof wrappings. The inner bark was employed as a dye. Bark was also used to make hats and baby cradles. The wood was used to make cooking tools such as bowls and spoons, canoe paddles, toboggans, and snowshoes.

Wildlife Value of the Paper Birch

Paper Birch trees are an important browse plant for some animals. Snowshoe Hares, Moose, Eastern Cottontail, Beaver, and Porcupines eat the twigs or bark. Red Squirrels feed on the catkins. Where winter food is inadequate, Paper Birch trees are also browsed by White-tailed Deer. This tree is the larval host for the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail, Luna Moth, and Mourning Cloak.

Paper Birch trees provide food and breeding habitat for a number of birds.

- The Ruffed Grouse eats the seeds and buds of Paper Birch.

- The seed-filled catkins also feed Black-capped Chickadees, Common Redpolls, Pine Siskins, and Fox Sparrows.

- Yellow-belled Sapsuckers chip holes in the bark, returning to feed on the sap that pools in the excavations.

- Several birds, notably Philadelphia Vireos, Red-shouldered Hawks, and Black-throated Green Warblers, use birch strips for nest construction.

The paper birch is a common tree species in the breeding habitat for several species of birds, including:

Veery

Northern Goshawk

Rose-breasted Grosbeak

Yellow-belled Sapsucker

Eastern Whip-poor-will

Black-capped Chickadee

Distribution of the Paper Birch

Paper Birch is native in northern North America. This species is widely distributed from northwestern Alaska, east across Canada to Labrador and Newfoundland, south to Pennsylvania and Iowa and in the western states to Montana and northeastern Oregon.

In New York State, the Paper Birch is found in most of the eastern counties, including the Catskills and the Adirondack Mountains. It is one of the most abundant hardwoods in the Adirondacks High Peaks region.

Habitat of the Paper Birch

Paper Birch is classified as a Facultative Upland (FACU) plant, meaning that it usually occurs in non-wetlands, but may occur in wetlands. It is a northern species adapted to cold climates and short growing seasons. This species is commonly found in mixed hardwood-conifer forests, but may form nearly pure stands where they pioneer areas disturbed by fires or logging. This tree grows best in the areas where average summer temperatures are not above 70 degrees. The tree does not perform well in harsh conditions or heat and is not tolerant of pollution.

- Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Red Pine Rocky Summit

- Sandstone Pavement Barrens

- Acidic Talus Slope Woodland

- Calcareous Red Cedar Barrens

- Successional Northern Hardwoods

Paper Birch is most abundant in disturbed areas, on sites recovering from burns, blowdowns, logging,and other disturbances, manmade and natural. On the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area (FERDA) plots at the Paul Smiths VIC, Paper Birch increased in abundance in both the shelterwood and clear cut blocks a decade after the cuts. The Paper Birch is also a common pioneer species on old fields. It usually lasts only one generation, before giving way to more shade-tolerant species.

Look for Paper Birch along many trails throughout the Adirondack Park. Paper Birch trees, like most other deciduous trees in the Adirondacks, prefer relatively well-drained soils. In contrast to Black Spruce and Tamaracks, Paper Birch trees do not grow in the middle of bogs or on very wet marsh edges. You will often find Paper Birch trees growing near Eastern Hemlock, Balsam Fir, and Hobblebush. Wildflowers often observed growing on the forest floor include Wild Sarsaparilla, Canada Mayflower, and Twinflower.

Adirondack Tree List

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 124-125.

E.H. Ketchledge. Forests and Trees of the Adirondacks High Peaks Region (Adirondack Mountain Club, 1996), pp. 107-110.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Betula papyrifera. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Betula papyrifera Marshall. Paper Birch. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Flora of North America. Betula papyrifera Marshall. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

L. O. Safford, John C. Bjorkbom, and John C. Zasada, "Betula papyrifera Marsh. Paper Birch," in Russell M. Burns and Barbara H. Honkala (Technical Coordinators), Silvics of North America: Hardwoods. Agriculture Handbook 654. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, DC. Volume 2. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

United States Department of Agriculture. NRCS National Plant Data Center. Plant Guide.

Paper Birch. Betula papyrifera Marsh. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Betula papyrifera. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Betula papyrifera. Marsh. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

Northern Forest Atlas. Paper Birch. Betula Papyrifera. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 102-103, 109-110, 121-122, 125. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Acidic Talus Slope Woodland. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Calcareous Red Cedar Barrens. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Red Pine Rocky Summit. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Sandstone Pavement Barrens. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Native Plant Database. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

Online Encyclopedia of Life. Betula papyrifera. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

Plants for a Future. Database. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), p.383.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Mourning Warbler, Veery, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Red-Shouldered Hawk, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Eastern Whip-poor-will, Northern Goshawk, Black-throated Green Warbler, and Black-capped Chickadee. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Black-capped Chickadee, Black-throated Green Warblers, Common Redpoll, Eastern Whip-poor-will, Fox Sparrow, Mourning Warbler, Northern Goshawk, Philadelphia Vireo, Pine Siskin, Red-shouldered Hawk, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Veery, Yellow-belled Sapsucker. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

Butterflies and Moths of North America. Canadian Tiger Swallowtail, Mourning Cloak, and Luna Moth. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

Ellen Rathbone, "Adirondack Tree Identification 102," The Adirondack Almanack, 18 November 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Winter Deer Foods. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Paper Birch. Betula papyrifera. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Eastern Trees (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), pp. 100-101, 313-314. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958,1972), pp. 231-232, 338-339. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, and Richard Spellenberg. Trees of Eastern North America (Princeton : Princeton University Press), pp. 154-155.

C. Frank Brockman. Trees of North America (New York: Golden Press, 1986), pp. 102-103. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

Keith Rushforth and Charles Hollis. Field Guide to the Trees of North America (Washington, D.C., National Geographic, 2006), p. 109.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Trees. Eastern Region (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983), Plates 179 and 615, pp. 368-369. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

John Kricher. A Field Guide to Eastern Forests. North America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), pp. 62-67, 122-123. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 304-305. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

Bruce Kershner, et al. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Trees of North America (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2008), pp. 399, 402.

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket. Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1992), pp. 25-30.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Trees (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), pp.150-151. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

Charles Fergus. Trees of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2002), pp. 89-92.