Birds of the Adirondacks:

Cape May Warbler (Setophaga tigrina)

Cape May Warblers (Setophaga tigrina) are small songbirds with off-white to yellow, streaked underparts, a narrow eyeline, and a fine, slightly decurved bill. They breed in boreal forests of Canada and northern US, including the Adirondack Mountains. Look for them foraging for spruce budworms on Red and Black Spruce trees.

The Cape May Warbler is a member of the New World Warbler or Wood Warbler family (Parulidae). It is one of at least 33 species that make up the Setophaga genus. This group of warblers includes other species, such as the Blackburnian Warbler and Palm Warbler, which breed in the Adirondack Mountains and other northern habitats in spring and summer and migrate south to warmer areas in the winter.

- The Cape May Warbler derives its English name from the fact that the first specimen was collected at Cape May, New Jersey, in 1811. The species reportedly was not seen in Cape May again until 1920.

- The Cape May Warbler was given its species name (tigrina) by Johan Friedrich Gmelin, a German naturalist, who allegedly named it for its tiger-like stripes. Another possibility is that the species name refers to its aggressive behavior defending its food sources.

- The Cape May Warbler was assigned to the Dendroica genus until 2011, when the American Ornithological Society reassigned it to the Setophaga genus as part of a larger rearrangement of Wood Warblers.

Cape May Warbler: Identification

Cape May Warblers are small and rather chunky, short-tailed warblers with extensively streaked underparts which vary from off white to bright yellow. These warblers have a yellow to greenish rump and a thin, very pointed bill which curves slightly downward. Cape May Warblers are about five inches long, with a wingspan of 7.63 inches, weighing in at an average of 0.41 ounces.

Adult males in breeding plumage (in spring) have bright yellow underparts, with the breast, sides and upper belly streaked with black. These birds sport a bold head pattern with bright orange-chestnut ear patches, a bright yellow neck, and black crown. They have a clear yellow rump patch and a white wing patch. Adult males in fall are similar, but drabber, with less chestnut in the face, a smaller wing patch, and a lighter crown.

Adult females in alternate (spring) plumage are less boldly colored than the male and lack the male's black cap and chestnut cheeks. Spring females have pale yellow underparts, with narrow, gray streaks on the breast and sides, a yellow rump, and two wing bars on each wing. In nonbreeding (basic) plumage, females are duller, with less distinct streaking. Immature females are extremely drab; they may be dull gray with only minimal yellowish color on the rump and blurry streaking on the underparts.

Several other warbler species are similar to the Cape May Warbler in appearance.

- Adult Palm Warblers in breeding plumage have a rusty cap, contrasting with the male Cape May Warbler's orange-chestnut ear patch. In addition, while Palm Warblers have white undertail coverts, those of Cape May Warblers are yellow.

- Female and immature Cape May Warblers are similar to female/immature Blackburnian Warblers. However, Blackburnian Warblers do not have streaking on the throat or central breast as the Cape May Warbler does.

- Another immature warbler that is similar to the immature Cape May is the Yellow-rumped Warbler. However, the Yellow-rumped Warbler has browner upper-parts and a white, unstreaked throat with yellow only on the sides, contrasting with the more extensive streaking on the Cape May.

Cape May Warbler: Songs and Calls

Cape May Warbler Song

Cape May Warblers have two song types. One is a very high-pitched, thin "seet seet seet seet seet." This song consists of, on average, five notes on one pitch of even cadence and volume, with about three to four notes per second. This song is similar to that of the Golden-crowned Kinglet, but it lacks the jumbled ending of the Kinglet's song.

The Cape May Warbler's alternate song consists of several two-syllable notes. This song is lower in pitch and is given at relatively longer intervals. One bird may sing both song types.

It is thought that only the male Cape May Warbler sings, usually from near the tops of spruce trees, singing for an extended period of time. Males reportedly sing frequently from late May to about mid-June. They are said to sing less frequently later in the breeding season.

The call of the Cape May Warbler is a very thin, high-pitched "tsip." The flight call is a high, soft, buzzy "seet."

Cape May Warbler: Behavior

Cape May Warblers appear to spend most of their time, at least in their breeding grounds, in the upper most branches of tall evergreens, particularly spruces. They feed on upper branches of spruce trees, usually choose the pinnacles of fir or spruce trees from which to sing, and place their nests at this level.

The Cape May Warbler is said to be an aggressive bird, defending its food sources and vigorously chasing other birds away from its favored feeding areas at all times of the year. Reports conflict on its flight pattern. One source describes it as fast and slightly undulating. Another states that its flight is slow and level, with shallow wing beats.

Cape May Warbler: Migration

The Cape May Warbler is a long-distance migrant. These birds winter in the Caribbean region, where they are found in a variety of habitats. Their winter range includes Bermuda, the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. A few winter in the Florida Keys.

- Sources conflict on the timing of spring migration, but most indicate that spring migration begins in late March, with the birds arriving on their breeding grounds in about mid-May. Most birds migrate at night, passing through Florida as they travel northward.

- Fall migration begins in August, with most birds having departed their breeding grounds by late September. Fall migration is said to follow a more easterly route through the northeastern Atlantic coastal states.

The Cape May Warblers we see here in the Adirondacks are either migrants passing through on their way to and from their wintering grounds or birds who breed and spend their summer here.

- Checklists from eBird indicate that spring sightings of Cape Mays within the Adirondack Park Blue Line begin in mid- to late May. Some of these birds are likely migrants on their way further north.

- Fall sightings of Cape May Warblers in the Adirondack Mountains suggest that most birds transit through or leave their breeding grounds in the Park by late September.

Cape May Warbler: Diet and Foraging

The main items on the menu for the Cape May Warblers we see here in the Adirondacks are insects, especially spruce budworms. The Cape May's diet during the breeding season also includes parasitic wasp and flies, ants, bees, small moths, beetles, and spiders.

Look for Cape May Warblers foraging near the tops of spruce and fir trees, hopping quickly from branch to branch while picking insects from the undersides of the needles. Cape Mays focus on the outer branches and tips of branches, perching on the branches or hanging head downward to pursue their prey. The birds may sometimes fly out several feet to capture flying insects in mid-air.

During migration and on their winter grounds, Cape May Warblers also consume flower nectar and fruit juices. This bird's tongue, which is unique among warblers, is curled and semi-tubular to assist in the collection of nectar.

Cape May Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

Although many details of the Cape May Warbler's breeding cycle remain unknown, most sources agree that Cape Mays build their nests high in spruce trees, often Black Spruce, in thick foliage near or against the trunk within a few feet of the top. The nest is a bulky cup composed of sphagnum moss, spruce twigs, and needles, lined with animal hair and feathers. Nests tend to be well hidden, which has made it difficult for observers during breeding bird surveys to confirm the presence of a breeding pair.

The Cape May Warbler is reported to have a larger average clutch size than most wood warblers. Females lay four to nine whitish eggs with red-brown spots, with an average clutch size of six. This large clutch size is thought to allow the populations of these warblers to expand rapidly during outbreaks of spruce budworms.

While little information is available on parental care or brooding, both parents appear to feed the nestlings. The age at which the young leave the nest is not known.

Distribution of the Cape May Warbler

Cape May Warblers breed in boreal forests in Canada and the northern United States. In Canada, breeding Cape May Warblers are found from southwestern Mackenzie and northern Alberta east through Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec and south to Algonquin Provincial Park.

In the US, Cape Mays breed in the northern Great Lakes Region, as well as northern New England and the Adirondack Mountains. An estimated 98% of Cape May Warblers breed in Canada.

Although conclusions regarding population trends for Cape May Warblers are complicated by the fact that their populations rise and fall with the rise and fall of spruce budworm outbreaks, most sources state that Cape May populations have been in decline since the late 1970s.

- The North American Breeding Bird Survey found that Cape May Warbler populations declined by over 2.5% per year between 1966 and 2015.

- Partners in Flight estimated that there was a 76% decline in Cape May Warbler populations from 1970 to 2014.

- The North American Bird Conservation Initiative's 2014 State of the Birds Report listed this species as a Common Bird in Steep Decline.

Threats to the Cape May Warbler include the loss of mature forest associated with logging. Modern lumber practices are also thought to have contributed to the Cape May's decline, due to the use of insecticides to control spruce budworms.

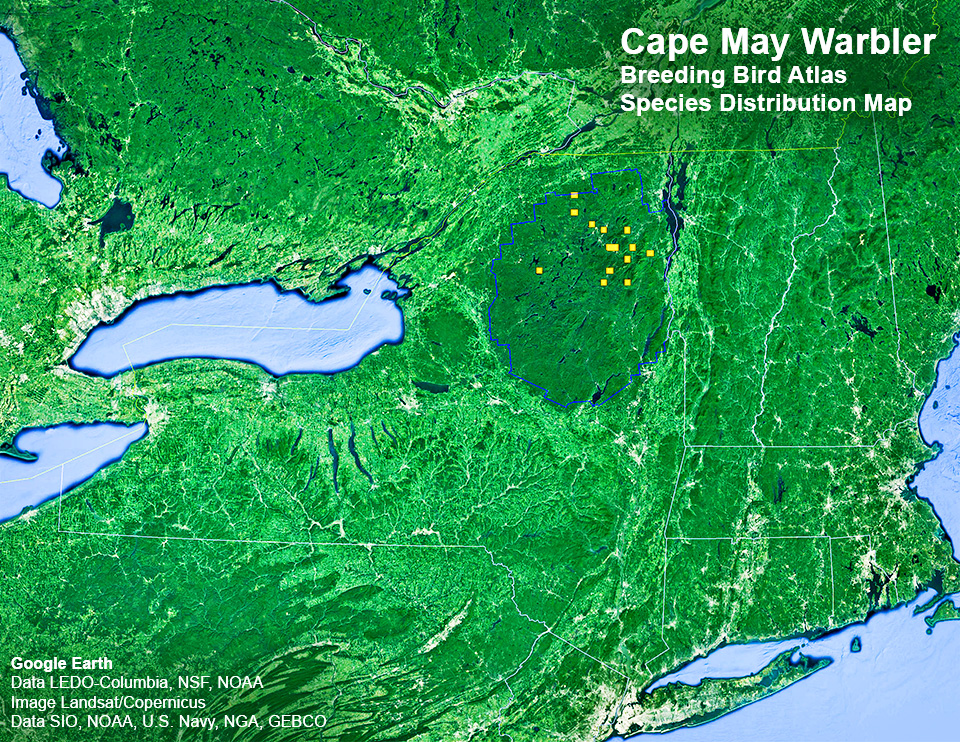

In New York State, which is south of this species' main breeding range, species accounts for the Cape May Warbler from the 1980-85 and 2000-05 Breeding Bird Surveys indicate that breeding for this species is restricted to the Adirondack Mountains.

- In the first New York breeding bird survey (1980-85), only 18 possible and probable records were obtained, mainly in the High Peaks and western Adirondacks. The second breeding bird survey (2000-05) yielded 14 locations, primarily in Franklin and Essex counties. The only confirmed record in both surveys was an 18 June 2000 sighting of adults carrying food for young along the West Branch of the Ausable River in North Elba (Essex County).

- So far, there has been one confirmed breeding in the third New York breeding bird survey (2020-2024). Recently-fledged young were observed on 24 July 2020 on the South Meadows Road in North Elba.

Cape May Warbler: Habitat

Cape May Warblers breed in boreal forests, usually in medium- to old-aged coniferous habitats with spruce (particularly Black Spruce) and Balsam Fir. This species appears to favor spruce stands with tall, well-developed crowns, as well as areas hit by spruce budworm outbreaks. On their breeding grounds, Cape Mays are usually found in more open woods or near forests edges. Cape May Warblers are said to use all types of woodland during migration.

Where to find Cape May Warblers in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Cape May Warblers

- Northern Region

- Whitney Wilderness

- Spring Pond Bog

- Bigelow Road

- Southern Region

- Pillsbury Mountain

- High Peaks Region

- The High Peaks

- Riverside Drive

- Adirondack Loj Road

- Marcy Dam

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack birders in search of Cape May Warblers have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the northern Adirondacks and High Peaks region, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide. Their list of birding sites for Cape Mays includes Bigelow Road and Spring Pond Bog in Franklin County, Riverside Drive and the Adirondack Loj Road in Essex County, and Pillsbury Mountain in Hamilton County.

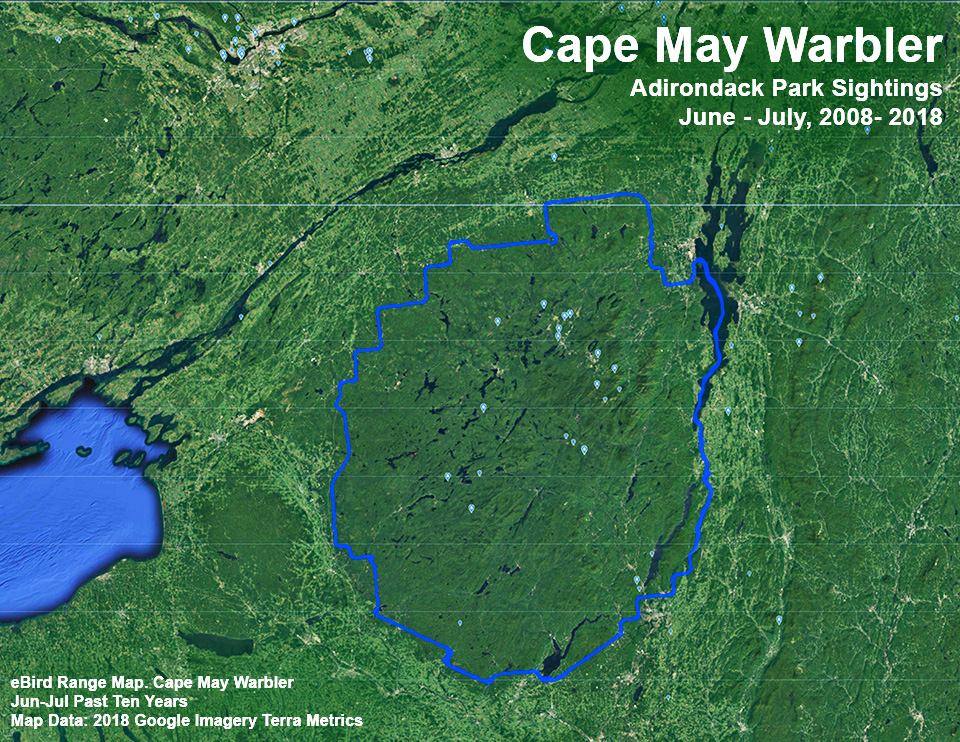

The pattern of Cape May Warbler eBird sightings during the breeding season is roughly consistent with the findings of the New York Breeding Bird Surveys. Most sightings in June and July are confined to the Adirondack Park. Most sightings cluster around known or suspected breeding sites, including Bloomingdale Bog in Franklin County, Intervale Lowlands in Essex County (near the Jackrabbit Trail on River Road, outside Lake Placid), and the Roosevelt Truck Trail in Essex County (near Long Lake).

Cape May eBird sightings for spring and late summer/fall are more widely distributed throughout the Adirondacks. Many of the birds seen during these times are almost certainly migrants on their way to or from breeding grounds to the north of us in Canada.

Among the trails covered here, the most likely locations to look for Cape May Warblers include the Bloomingdale Bog Trail (particularly locations around Bigelow Road), John Brown Farm, and the Jackrabbit Trail at River Road.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birds of the World. Subscription Web Site. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Macaulay Library. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

North American Bird Conservation Initiative (NABCI). 2014 State of the Birds Report. Common Birds in Steep Decline. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Xeno-canto Database. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

eBird. Bird Observations. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

eBird. Species Maps. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

iNaturalist. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Cape May Warbler. Dendroica tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map. Cape May Warbler. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

John M.C. Peterson, "Cape May Warbler," in Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 486-487, 640.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 35.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), p. 98.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), pp. 154,199.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 61-65, 70-77, 91-94, 114-116

131-133, 189-192.

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Trend Estimate by Species. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Species Map. Cape May Warbler. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

Vermont Atlas of Life. Vermont Breeding Bird Species Profiles. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas 1. Species Maps. Cape May Warbler. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013. Population Estimates Database, version 2013. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan. 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States, pp. 110-111, 114-115. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Verne E. Davison. Attracting Birds from the Prairies to the Atlantic (Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1967), p. 140.

Margaret McKenny. Birds in the Garden and How to Attract Them (Grosset & Dunlap, 1939), pp. 185, 193, 224.

David Allen Sibley. Sibley Birds East. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 350.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), p. 482.

Roger Tory Peterson. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Sixth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), pp. 271-272, Map 398.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Eastern Region (Little, Brown and Company, 2013), pp. 366-367.

Jonathan Alderfer, Ed. Complete Birds of North America. Second Edition (National Geographic, 2014), p. 606.

Richard Crossley. The Crossley ID Guide (Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 411.

American Museum of Natural History. Birds of North America. Revised Edition (Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2016), p. 585.

John Bull and John Farrand, Jr. Eds. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. Eastern Region. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), pp. 665-666.

Edward S. Brinkley. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), p. 385.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 27, 36, 43, 45, 46, 48, 158, 174, 184, 194, 222-231, 405, 436, 482, 529, 537, 542, 546.

Chris G. Early. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 46-47.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 128-133.

Jon Curson, David Quinn and David Beadle. Warblers of the Americas. An Identification Guide (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), pp. 32-33, 120-121.

Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett. A Field Guide to Warblers of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), pp. 64-65, 248-257.

Paul Sterry. Warblers and Other Songbirds of North America: A Life-size Guide to Every Species (Harper-Collins Publishers, 2017), p. 203.Arthur Bent. Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers. Part One and Part Two (Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 203, 1953), pp. 212-224. Kindle Book. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Cape May Warbler. Setophaga tigrina. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 397- 400, Plate 93. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

Douglass H. Morse, "Populations of Bay-Breasted and Cape May Warblers during an Outbreak of the Spruce Budworm," The Wilson Bulletin, Volume 90, Number 3 (September, 1978), pp. 404-413. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Geoffrey Carleton, Hustace H. Poor and Oliver K. Scott, " Cape May Warbler Breeding in New York State," The Auk, Volume 65, Number 4 (October 1948), p. 607. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Robert H. MacArthur, “Population Ecology of Some Warblers of Northeastern Coniferous Forests,” Ecology, Volume 39, Number 4 (October 1958), pp. 599-619. Retrieved 4 February 2020.