Birds of the Adirondacks:

Black-throated Blue Warbler (Setophaga caerulescens)

The Black-throated Blue Warbler (Setophaga caerulescens) is a midnight blue bird with black and white markings. It breeds in deciduous and mixed forest in the Adirondacks.

The Black-throated Blue Warbler is a member of the New World warbler or wood warbler family (Parulidae).

- Wood warblers subsist mainly on insects during breeding season and are primarily foliage gleaners, with slender, pointed bills. Most are active and often brightly colored. As the name implies, wood warblers are partial to wooded habitats.

- There are about 120 species in the wood warbler family, currently divided into 18 genera. The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (2008) lists 33 warbler species (plus one hybrid) that breed in New York State; 29 are listed as possible, probable, or confirmed breeding birds in the Adirondack Park. All are migratory. Most arrive in the Adirondack Mountains in late April or early May and depart in September or October.

The Black-throated Blue Warbler is currently assigned to the Setophaga genus, a large group which includes many other warblers that breed in the Adirondacks, including the Blackburnian Warbler, Palm Warbler, Cape May Warbler, Northern Parula, Magnolia Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Pine Warbler, Blackpoll Warbler, and Yellow Warbler.

- The Black-throated Blue Warbler was previously assigned to the Dendroica genus. In 2011, as part of a larger rearrangement of Wood Warbler taxonomy, based on DNA studies, the Dendroica genus was merged with the Setophaga genus, which now contains at least 33 species. Older publications list the Black-throated Blue Warbler as Dendroica caerulescens.

- The name Setophaga is derived from the Greek ses ("moth") and phagos ("eating"). The species name (caerulescens) is derived from the Latin caeruleus, meaning "dark blue."

The Black-throated Blue Warbler has been the focus of a large body of research, analyzing its foraging behavior, mating system, patterns of parental care, and response to environmental change, among other issues.

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Identification

Black-throated Blue Warblers are about 5.2 inches in length from the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail, with a wing span of 7.5 inches. They weigh in at 0.37 ounces. Compared to other warblers, they are medium-sized, larger than the tiny Northern Parula (4.4 inches long), but significantly smaller than the Ovenbird (6 inches long, weighing in at .0.71 ounces).

While most temperate-zone warblers are moderately dimorphicSexual Dimorphism: The condition where the two sexes of the same species exhibit different characteristics beyond the differences in their sexual organs. In birds, sexual dimorphism can be manifested in size or plumage differences between the sexes. Males are typically the more ornamented or brightly colored sex. , with males more brightly colored than the females, male and female Black-throated Warblers are strikingly different in appearance. In fact, they are so different that early naturalists, including Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon, considered them to be separate species. The only major field mark the two sexes share is a white wing patch, which helps to distinguish the female from other warblers with similar coloration.

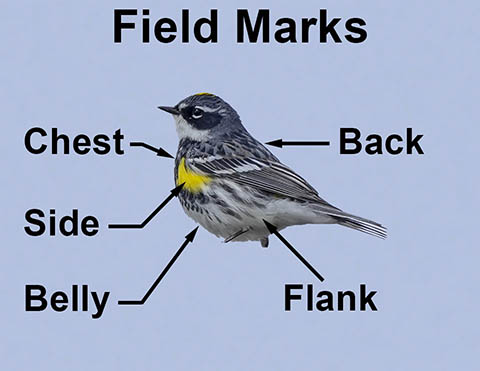

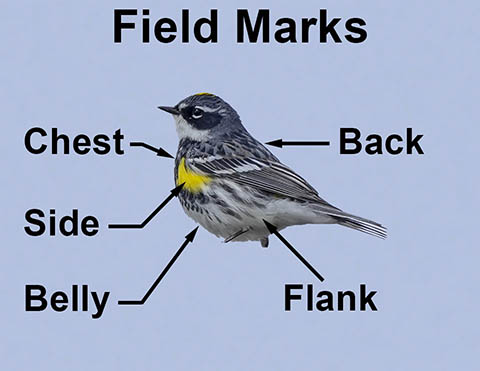

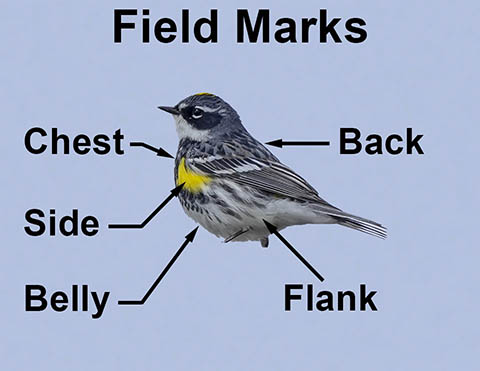

With their distinctive midnight blue, black, and white plumage, adult male Black-throated Blue Warblers are unique. Males are dark royal blue on the top of the head, down the back, and into the tail. The chest Chest: The chest (also called the breast) is the upright part of the bird’s body between the throat and the abdomen. and underparts are a bright white. The throat, face, and flanks

Chest: The chest (also called the breast) is the upright part of the bird’s body between the throat and the abdomen. and underparts are a bright white. The throat, face, and flanks Flank: The lateral area posterior to the side region, lying below the pelvis and extending back to the base of the tail. are black. The male has large white tail spots

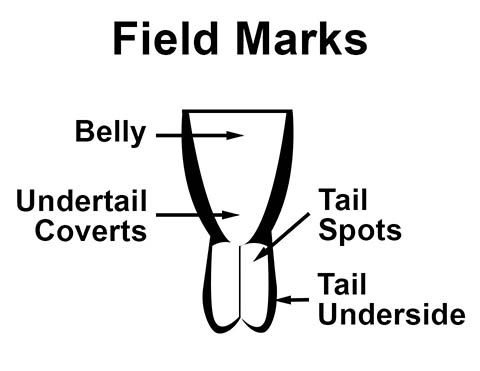

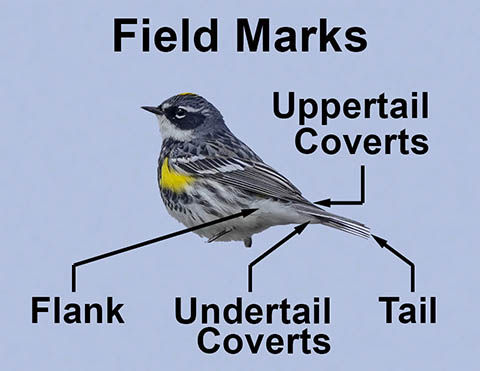

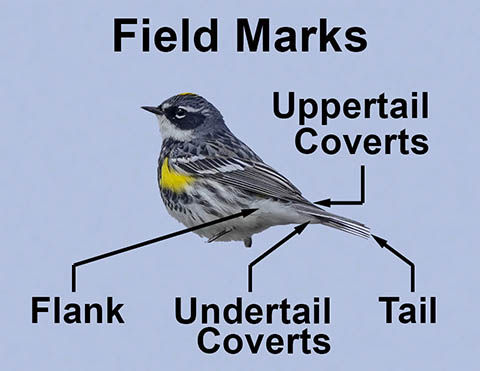

Flank: The lateral area posterior to the side region, lying below the pelvis and extending back to the base of the tail. are black. The male has large white tail spots Tail Spots: the white or pale area surrounded by dark near end of outer tail feathers. bordered by black at the base and white undertail coverts

Tail Spots: the white or pale area surrounded by dark near end of outer tail feathers. bordered by black at the base and white undertail coverts Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail.. There is no streaking on the back. Male Black-throated Blue Warblers have a white wing stripe which appears as a small white patch or "handkerchief" when the wing is folded. Male Black-throated Blue Warblers, in contrast to many other warblers that breed in our area, do not undergo major plumage changes in the fall.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail.. There is no streaking on the back. Male Black-throated Blue Warblers have a white wing stripe which appears as a small white patch or "handkerchief" when the wing is folded. Male Black-throated Blue Warblers, in contrast to many other warblers that breed in our area, do not undergo major plumage changes in the fall.

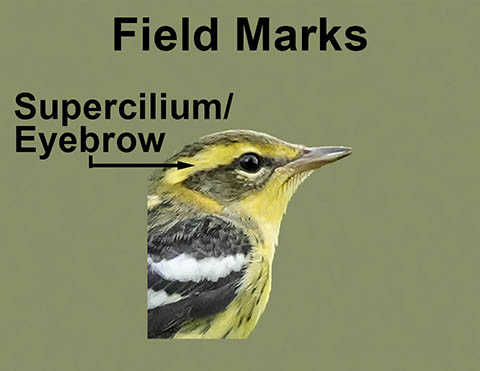

Adult female Black-throated Blue Warblers look nothing like the male; females are olive-brown or grayish olive overall, with lighter underparts. The head is olive brown. Females have a whitish or cream eye stripe (supercilium Supercilium/Eyebrow: The area of contrast above the bird's eye.) and a light undereye eye crescent

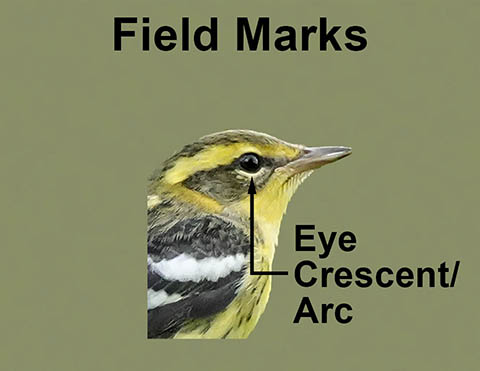

Supercilium/Eyebrow: The area of contrast above the bird's eye.) and a light undereye eye crescent Eye Crescent/Arc: A partial ring around the eye of the bird. A complete ring around the eye is called an eye ring.. The cheek is dark. Like the males, females lack wing bars, but usually have a small patch of white on on their wings when folded. Female Black-throated Blue Warblers, like their male counterparts, do not undergo major plumage changes in the fall.

Eye Crescent/Arc: A partial ring around the eye of the bird. A complete ring around the eye is called an eye ring.. The cheek is dark. Like the males, females lack wing bars, but usually have a small patch of white on on their wings when folded. Female Black-throated Blue Warblers, like their male counterparts, do not undergo major plumage changes in the fall.

Juvenile Black-throated Blue Warblers are similar to their adult counterparts. Hatch-year males do not look like females; they are blue and black like adult males. Their back and head feathers are sometimes edged with green. Female immature Black-throated Blue Warblers are similar in appearance to adult females, although the white spot on the wing may be smaller or even absent.

The male Black-throated Blue Warbler is distinctive and is unlikely to be confused with other warblers, except possibly the male Cerulean Warbler – another blue, black, and white warbler that breeds in parts of New York State, but rarely within the Adirondack Park Blue Line. The male Cerulean Warbler is a somewhat lighter blue than the male Black-throated Blue Warbler, and its throat is bright white rather than black. The Cerulean Warbler also has two white wing bars, rather than the Black-throated Blue's white wing patch.

Identifying the female Black-throated Blue Warbler is more difficult, because there are several other warblers seen in the Adirondack Park with somewhat similar plumage.

- Nonbreeding and immature Tennesee Warblers have a yellow wash on their throats and flanks

Flank: The lateral area posterior to the side region, lying below the pelvis and extending back to the base of the tail., in contrast to the female Black-throated Warbler, which is more brownish. In addition, the Tennesee Warbler lacks the white handkerchief on the wing of the Black-throated Blue. Tennessee Warblers breed in the Adirondack Park, but they are not an abundant species in our area.

Flank: The lateral area posterior to the side region, lying below the pelvis and extending back to the base of the tail., in contrast to the female Black-throated Warbler, which is more brownish. In addition, the Tennesee Warbler lacks the white handkerchief on the wing of the Black-throated Blue. Tennessee Warblers breed in the Adirondack Park, but they are not an abundant species in our area. - Orange-crowned Warblers have a more greenish plumage than female Black-throated Blue Warblers. However, their undertail coverts

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are yellow, in contrast to the Black-throated Blue Warbler, which has white undertail coverts. Orange-crowned Warblers also lack the Black-throated Blue's diagnostic white "handkerchief" on the wing. The Orange-crowned Warbler breeds in Canada, to the north of us, and is seen within the Adirondack Park Blue Line only in migration and then very rarely.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are yellow, in contrast to the Black-throated Blue Warbler, which has white undertail coverts. Orange-crowned Warblers also lack the Black-throated Blue's diagnostic white "handkerchief" on the wing. The Orange-crowned Warbler breeds in Canada, to the north of us, and is seen within the Adirondack Park Blue Line only in migration and then very rarely.

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Songs and Calls

As with most warblers, the male Black-throated Blue Warbler is the main singer, although there have been reports of females singing occasionally. Male Black-throated Blues sing at least two different songs. These songs reportedly do not vary strongly across geographic regions.

The most frequent song consists of three to seven repeated buzzy notes. The initial section of the song is relatively even in pitch or slightly descending, followed by a final note which is slurred upward. A mnemonic found useful to many birders is: "I am so lay-ZEEE." The song has been described variously as harsh, husky, relaxed, drawling, and slow-paced.

This song is used almost exclusively by males during the breeding season. The male sings from perches in the lower to middle levels of vegetation, usually located in the center of his territory. Although the frequency of singing is highest from the male's arrival in early May through July or early August, Black-throated Blue Warblers tend to sing later than many other species that breed in these forests, with some individuals singing well into August and early September. Song frequency declines in later stages of the nest cycle.

A second song type consists of two to six buzzy notes, delivered with a more even tempo. This song has either an unslurred ending or a downward slur and is said to be lower in pitch than the Type 1 song. This song is reportedly used at territorial boundaries or during aggressive encounters between males.

The Black-throated Blue Warbler's call, given by both males and females, is a flat sounding "tik," said to be similar to the call note of the Dark-eyed Junco. The Black-throated Blue Warbler's flight note is a prolonged "tseet."

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Behavior

Black-throated Blue Warblers are territorial on their breeding grounds. Males defend and advertise their territories through singing and respond aggressively to intruders, initially signaling their aggressive intentions through vocalizations and body language. If that doesn't work, territorial disputes often escalate into prolonged chases and conflicts, with the aggressor landing on the back of its opponent, pecking its rival with the beak and striking it with its wings.

During breeding season, male Black-throated Blue Warblers spend about half their time foraging or singing while foraging, with the rest of the time spent singing from perches, preening, and engaging in aggressive interactions. Female Black-throated Blue Warblers spend about 75% of their daylight hours incubating and the rest foraging. After the eggs hatch, both members of the pair forage for about ¾ of their time.

Black-throated Blue Warblers respond aggressively to predators, which include Eastern Chipmunks, Red Squirrels, American Martens, and Fishers. Black-throated Blue Warbler pairs react to intruders that approach their nest by mobbing. If flushed from her nest, the female typically performs a distraction display, flapping her wings and giving high-pitched twitters.

In their response to human observers, Black-throated Blue Warblers are not especially shy. They are said to be among the tamest and most trusting of the warblers and will tolerate observers to within a few feet.

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Migration

Black-throated Blue Warblers are Neotropical migrantsNeotropical migrant/Neotropical migratory birds: Any species of bird whose breeding area includes the North American temperate zones and that migrates south of the continental United States during nonbreeding seasons. Neotropical migrant birds breed in North America during the spring and early summer and spend the winter in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America.. They breed in the northeastern US and southeastern Canada and spend the winter in the Caribbean. This species is one of 386 birds (including 50 warblers) covered by the Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act.

Black-throated Blue Warblers are considered to be medium to long-distance migrants. They overwinter in the Greater Antilles from Puerto Rico to Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola. Some individuals spend the winter in the Bahamas or along the coast of the Yucatan and Belize. A very few individuals overwinter in south Florida.

The spring migration begins in late March to the middle of April, when Black-throated Blue Warblers depart their wintering grounds. They move north through Florida and then move up along the Atlantic seaboard, with most birds staying east of the Appalachians. The birds arrive on their breeding grounds from late April in the south to mid-May in the north.

The fall migration is the inverse of the spring migration. Black-throated Blue Warblers (like the Chestnut-side Warbler, Nashville Warbler, and Cape May Warbler) are considered to be relatively late fall migrants, departing their breeding grounds starting in mid- and late August through early October. They migrate southward on a wide front along the eastern seaboard, between the Appalachians and the Atlantic coast. Individuals from the northeastern parts of their breeding grounds move down the Atlantic coast to Florida and then cross to the West Indies. Individuals who breed further west move in a southeasterly direction, across the southern Appalachians, to reach Florida. The birds arrive on their wintering ground starting in late September.

The Black-throated Blue Warblers we see here in the Adirondacks are either migrants headed for Canada passing through on their way to and from their wintering grounds or birds who breed and spend their summer here.

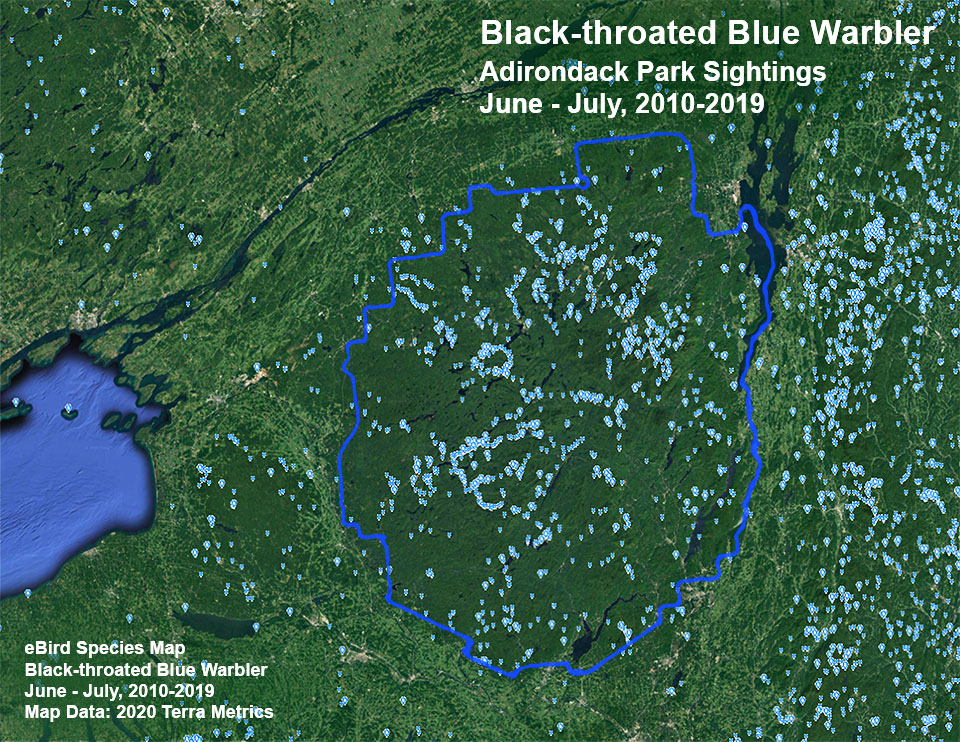

- Black-throated Blue Warblers appear to arrive in the Adirondack region starting in very late April. Most appear in the first week or two of May. The pattern of eBird sightings in the six core Adirondack counties (Essex, Hamilton, Warren, Herkimer, Clinton, and Franklin) show the highest number of reports in the last week of June through the first two weeks of July.

- Although it is difficult to disentangle sightings which reflect birds which breed in the Adirondacks and those reflecting birds which are migrating south through our area from Canada, it appears that most Black-throated Blue Warblers who breed in the Adirondacks probably leave in late September and early October. By mid-October, most Black-throated Blue Warblers appear to have left the Adirondack region, with a few stragglers reported in the third week of October.

Black-throated Blue Warblers are nocturnal migrants. During migration, they are seen in a variety of habitats, including gardens, parks, and forests.

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Diet and Foraging

As with other New World Warblers, Black-throated Blue Warblers feed primarily on insects on their breeding grounds. Their menu during this time includes spiders, crane flies, moths, and caterpillars.

Like many other warbler species, Black-throated Blue Warblers search for prey primarily on the surface of vegetation. This sets them apart from bark gleaners (like Black-and-white Warblers or Red-breasted Nuthatches) and flycatchers (birds that fly out to catch flying insects, like American Redstarts). Black-throated Blue Warblers take prey mainly from the undersides of leaves. They concentrate their foraging on deciduous foliage, with coniferous vegetation consistently ignored.

Black-throated Blue Warblers forage for their prey at low- and mid-levels, in contrast to species like Blackburnian Warblers and Cape May Warblers, which forage high in the treetops and others like the Northern Waterthrush or the Hermit Thrush, which that forage on the forest floor.

Male and female Black-throated Blue Warblers use different substrates. Females forage more frequently in the lower shrub zone (between one and three meters high), closer to nest height. Males, by contrast, tend to forage at somewhat higher levels (between three and nine meters high), probably because their other main activities (territorial defense and advertisement) take place at higher levels. Later in the breeding season, when the males assist in feeding fledglings, they also begin foraging at lower levels.

During migration and on their wintering grounds, foraging patterns and diet change. During migration, Black-throated Blue Warblers forage in all types of woodlands, parks, and gardens. While on their wintering grounds, they will often supplement their diet with berries, seeds, small fruits, and flower nectar.

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

The breeding cycle for Black-throated Blue Warblers begins when the males arrive on their breeding grounds and establish territories. The adult males are followed within a few days by females, after which pairing takes place. Pairs generally remain together during a breeding season. Adults often return to the same breeding area in subsequent years.

Nest building, which typically takes three to five days, begins within three to seven days after the female's arrival. Nests are constructed from thin strips of birch bark (from Paper Birch or Yellow Birch), with the inner wall composed of shredded bark fibers and lined with pine needles, moss, and rootlets. Nests are typically located in dense shrubs (such as Hobblebush) or saplings, usually around five or six feet from the ground. The nest site is usually chosen by the female, who also does the construction.

Female Black-throated Blue Warblers lay of clutch of two to five (usually four) eggs. Incubation, which is done solely by the female, takes 12-13 days. Nestlings depart the nest after eight to ten days. Both males and females feed the nestlings.

Distribution of the Black-throated Blue Warbler

The Black-throated Blue Warbler breeds in the northeastern US and southeastern Canada. Its breeding range extends from western Ontario east to southern Quebec and Nova Scotia and south to Minnesota, the Great Lakes region, and Connecticut. The species also breeds at higher elevations in the southern Appalachians from northern Georgia, the western portions of South Carolina and North Carolina, eastern Tennessee and Kentucky, and north to western West Virginia.

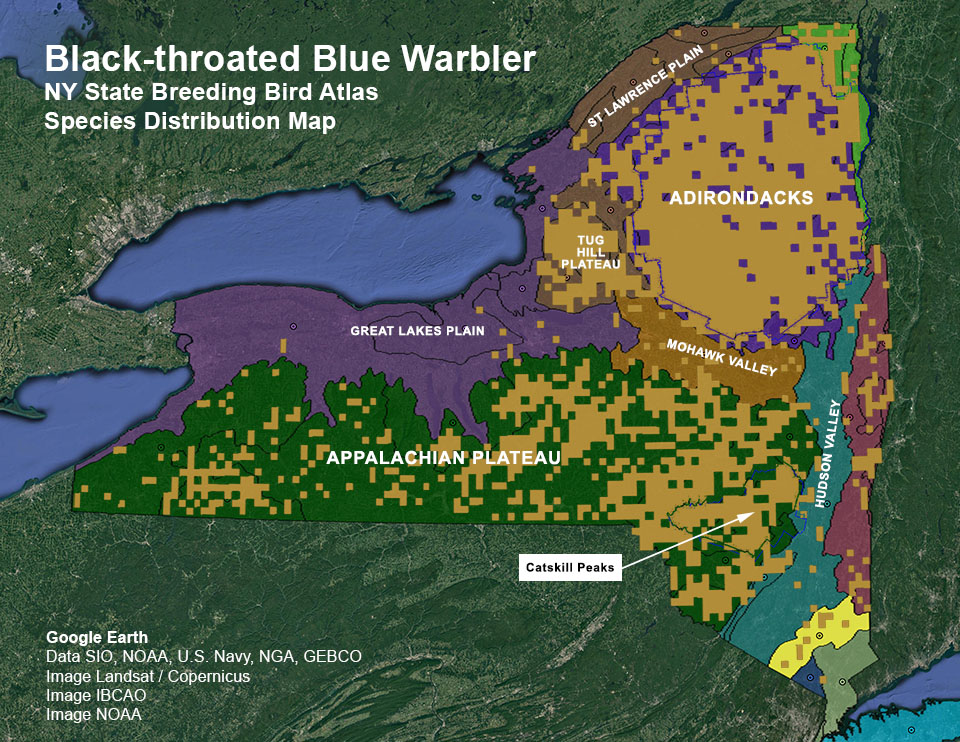

In New York State, Black-throated Blue Warblers breed mainly in sites above 1,000 feet, with concentrations in the Adirondacks and the eastern Appalachian Plateau.

- In the 1980-1985 New York State Breeding Bird survey, most of the confirmed breeding sites were clustered in the Adirondack Mountains, particularly the southwestern areas, with some additional sites in the Appalachian Plateau and Catskill Mountains. A few blocks with confirmed breeding birds were found in the eastern parts of New York State (Taconic Foothills and Rensselaer Hills).

- The overall distribution of breeding Black-throated Blue Warblers did not change appreciably in the 2000-2005 New York State Breeding Bird Survey. There were fewer confirmed sites, but more probable sites. Blocks with possible, probable, or confirmed breeding birds were clustered in Adirondacks, Tug Hill area, and Appalachian Plateau, especially the eastern part of it. The species was virtually absent from the lower elevations, including major river valleys.

- More recent trends affecting Black-throated Blue Warblers in New York State will become clearer as data emerge from the third New York Breeding Bird Atlas, which began on 1 January 2020. This atlas, which covers 2020-2024, will use eBird for data collection, offering real-time data output.

The Black-throated Blue Warbler is of low conservation concern. According to Partners in Flight, the overall population of this species increased by 163% between 1970 and 2014, with an estimated population of 2.4 million individuals. The 2000 Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for the Adirondack Mountains indicated that populations of the Black-throated Blue Warbler in the Adirondack Park are stable.

The long-term future of the Black-throated Blue Warbler is uncertain. While the species still appears to be recovering from declines in the 18th and 19th centuries due to widespread clearcutting, future climate changes affecting habitats in its breeding, wintering, and migratory stopover regions could affect the distribution and abundance of this species.

Causes of mortality for individual Black-throated Blue Warblers are also unclear. The oldest Black-throated Blue Warbler on record is a 10-year-old female banded in New Jersey and shot in Panama. While average life span is not known, it is likely that many Black-throated Blue Warblers do not make it that long.

- Nestlings may die of exposure or starvation during cold, rainy periods.

- Another major cause of mortality is predation. Raptors prey primarily on adults. Both nestlings and newly fledged Black-throated Blue Warblers are vulnerable to predation by a variety of mammals, particularly the Eastern Chipmunk, which has been identified as a serious nest predator. A 1975 study of Black-throated Blue Warblers in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire found a correlation between chipmunk numbers and nest predation.

- Black-throated Blue Warblers also appear to more susceptible than most species to mortality associated with communication tower and window collisions.

Black-throated Blue Warbler: Breeding Habitat

The Black-throated Warbler breeds in northern hardwood or mixed forest, with an apparent preference for hardwood forests. One of their habitat requirements is a thick understory of shrubs. A 1989 study of Black-throated Blue Warblers in the southern White Mountains of New Hampshire found a positive relationship between shrub density and Black-throated Blue Warbler density. After shrub foliage was removed from one plot, Black-throated Blue Warbler density declined to zero after three years, while density on other plots was stable.

In New York State, Black-throated Warblers are found in a variety of hardwood and mixed forest ecological communities, including Beech-Maple Mesic Forest, Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest, and Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. The plant species in the shrub layer varies. In our area, Black-throated Blue Warblers appear to favor sites that include dense stands of Hobblebush, Mountain Maple, Striped Maple, as well as the saplings of other deciduous trees.

Sources conflict on the extent to which Black-throated Blue Warblers require mature forests on their breeding grounds. Many sources state that this species favors mature forests, while others indicate this warbler (like the Mourning Warbler) is at home in second-growth forests that develop after selective cutting. In any event, a preference for mature forest was not evident in a 1977 study of the response of songbird populations to logging. The study was conducted between 1953 and 1962 in the Huntington Wildlife Forest in the central Adirondacks. The researchers found that while some species, such as the Blackburnian Warbler, Ovenbird, and Black-throated Green Warbler, decreased significantly in response to logging activities, Black-throated Blue Warbler populations did not appear to be significantly affected by logging.

Where to find Black-throated Blue Warbler in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Black-throated Blue Warblers

- Eastern Region

- Lake Alice

- West Central Region

- Wakely Mountain

- Third Lake Creek

- South Inlet

- Ferd's Bog

- Pepperbox Wilderness

- Beaver Lake

- High Peaks Region

- Riverside Drive

- Marcy Dam

- Lyon Mountain

- Northville-Placid Trail (Long Lake)

- Northern Region

- Five Ponds Wilderness

- Jones & Osgood Ponds

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack birders in search of Black-throated Blue Warblers have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the the west-central region, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide. Their list of birding sites for Black-throated Blue Warblers includes Wakely Mountain, Ferd's Bog, the Northville-Placid Trail, and Lake Alice in Hamilton County; Marcy Dam in Essex County; and Lyon Mountain in Clinton County.

The pattern of eBird sightings for the Black-throated Blue Warbler during breeding season is roughly consistent with the Peterson/Lee recommendations and the findings of the two New York State Breeding Bird Surveys. Sightings of Black-throated Blue Warblers reported through eBird are more numerous inside the Adirondack Park, despite the fact that there are almost certainly more eBirders outside the Park. There are also concentrations of eBird sightings in the Appalachian Plateau (mostly south of the Finger Lakes) and the western Tug Hill area.

The list of eBird sightings for the Black-throated Blue Warbler within the Adirondack Park includes clusters of reports in popular birding hot spots, such as Massawepie Mire in Saint Lawrence County; Lake Alice and the Silver Lake Bog Preserve in Clinton County; the Peninsula Nature Trails, Adirondak Loj, and Adirondack Interpretive Center in Essex County; Bloomingdale Bog (both South Entrance and North Entrance), the Paul Smith's College VIC, Osgood Pond, Madawaska Pond, and Blue Mountain Road in Franklin County; and Moose River Plains, Ferd's Bog, Blue Mountain Trail, Sabattis Road, and Sabattis Bog in Hamilton County.

Among the trails covered here, the most likely locations to look for Black-throated Blue Warblers include mixed forest and hardwood forest habitat on most of the trails at the Paul Smith's College VIC, the Peninsula Nature Trails in Lake Placid, Heart Lake Trail, Jackrabbit Trail at River Road, Cemetery Road Wetlands, John Brown Farm, and Henry's Woods.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Setophaga. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Warren, Hamilton, Essex, Herkimer, Clinton, Franklin). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Essex). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton, Essex). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Fulton, Hamilton, Herkimer, Lewis, Oneida, Saratoga, St. Lawrence, Warren, Washington counties). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Species Maps. Black-throated Blue Warbler . Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Kevin McGowan. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Bird Academy. Be a Better Birder: Warbler Identification. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

Xeno-canto Database. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

G.A. Gough, J.R. Sauer, and M. Iliff. Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter. 1998. Version 97.1. Black-throated blue warbler. Dendroica caerulescens. Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

USGS. Longevity Records of North American Birds. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Dendroica caerulescens. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map (Google Earth). Retrieved 22 January 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 1980-1985. Release 1.0. Updated 6 June 2007. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 2000-2005. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

Joan E. Collins, "Black-throated Blue Warbler," in Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 488-489.

Richard F. Bonney, Jr., "Black-throated Blue Warbler," in Robert F. Andrle and Janet R. Carroll (Eds.) The Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 1988). pp. 376-377.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Breeding Guideline Bar Chart. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Breeding Season Table from Atlas 2000. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Hints on Haunts. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 35.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), p. 98.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), p. 174, Plate 33.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 59-60, 70-72, 75-77, 88-90, 98-101, 126-128, 147-154, 161-162, 175-177, 178-180, 209-209.

J. R. Sauer, D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. Trend Esimates for Core Survey Data. 1966 - 2017. Version 5.03.2019. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

J. R. Sauer, D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Trend Estimate by Species. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

Vermont Atlas of Life. Vermont Breeding Bird Species Profiles. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Mass Audubon. Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Species Accounts. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Dendroica caerulescens. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

A.T. Chartier, J. J. Baldy, and J. M. Brenneman. 2011. The Second Michigan Breeding Bird Atlas, 2002-2008. Results and Highlights. Kalamazoo Nature Center, Kalamazoo, MI (2011), p. 22. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas I. Species Maps. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas II (2015-2019). Black-throated Blue Warbler. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Setophaga caerulescens. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Partners in Flight. 2019. Population Estimates Database. Version 3.0. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan. 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States, p. 111. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Partners in Flight. Bird Conservation Plan for the Adirondack Mountains, pp.10-11, 23, 35. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

David Allen Sibley. Sibley Birds East. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 352.

Kimball L. Garrett and John B. Dunning, Jr., "Wood-Warblers," in Christ Elphick, John B. Dunning, Jr., and David Allen Sibley (eds.), The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), pp. 492-509.

Roger Tory Peterson. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Sixth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), pp. 270-271, Map 399.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Eastern Region (Little, Brown and Company, 2013), p. 377.

Richard Crossley. The Crossley ID Guide (Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 424.

John Bull and John Farrand, Jr., Eds. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. Eastern Region. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), pp. 666-667, Plates 600, 610.

Edward S. Brinkley. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), p. 373.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. Stokes field guide to warblers (Little, Brown, 2004), pp. 136-137.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 186-195.

Chris G. Earley. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 44-45. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 133-140. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Jon Curson, David Quinn and David Beadle. Warblers of the Americas. An Identification Guide (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), pp. 36, 121-123. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett. A Field Guide to Warblers of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), pp. 257-266, Plate 10. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Douglass H. Morse. American Warblers: An Ecological and Behavioral Perspective (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 161-162, 104-107, 179, 212.

Alexander Sprunt, Jr., "Black-throated Blue Warbler," in Ludlow Griscom, Alexander Sprunt, Jr. et al., Eds. The Warblers of North America (The Devin-Adair Company, 1957), pp. 87- 89, Plate 11. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

Arthur Bent. Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers. Part One and Part Two (Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 203, 1953), pp. 224-236. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

Paul Sterry. Warblers and Other Songbirds of North America: A Life-size Guide to Every Species (Harper-Collins Publishers, 2017), p. 212.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 119-121. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Beech-Maple Mesic Forest. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

The Nature Conservancy. Terrestrial Habitats. New York State. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

The Nature Conservancy. Laurentian-Acadian Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

The Nature Conservancy. Laurentian-Acadian Red Oak-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

The Nature Conservancy. Laurentian-Acadian Pine-Hemlock-Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

The Nature Conservancy. Appalachian (Hemlock)-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Black-throated Blue Warbler. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

Aretas A. Saunders. The Summer Birds of the Northern Adirondack Mountains. Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin. Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 326-499. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Theodore Roosevelt, "The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, N.Y.," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 501-504. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Perley M. Silloway, "Relation of Summer Birds to the Western Adirondack Forest," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 4 (March 1923), pp. 396-486. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 16, 21, 403-405. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

C. Hart Merriam, "Preliminary List of Birds Ascertained to Occur in the Adirondack Region. Northeastern New York," Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, Volume 6, Number 4 (October 1881), pp. 225-235. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

Richard T. Holmes, Craig Patrick Black and Thomas W. Sherry, "Comparative Population Bioenergetics of Three Insectivorous Passerines in a Deciduous Forest," The Condor, Volume 81, Number 1 (February 1979), pp. 9-20. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Craig Patrick Black. The Ecology and Bioenergetics of the Northern Black-Throated Blue Warbler (Dendroica caerulescens caerulescens)," Ph.D Dissertation, Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire (July 1975). Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Benjamin B. Steele. Habitat Selection by Breeding Black-throated Blue Warblers. Different Patterns at Two Spatial Scales and the Use of Habitat for Foraging and Nesting. Ph.D. Dissertation. Dartmouth College. Hanover, New Hampshire (March 1989). Retrieved 28 January 2020.

Scott K. Robinson and Richard T. Holmes, "Foraging Behavior of Forest Birds: The Relationships Among Search Tactics, Diet, and Habitat Structure," Ecology, Volume 63, Number 6 (December 1982), pp. 1918-1931. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

William L. Webb, Donald F. Behrend and Boonruang Saisorn, "Effect of Logging on Songbird Populations in a Northern Hardwood Foŗest," Wildlife Monographs, Number 55 (July 1977), pp. 3-35. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

Floyd E. Hayes, "Definitions for Migrant Birds: What Is a Neotropical Migrant?" The Auk, Volume 112, Number 2 (April 1995), pp. 521-523. Retrieved 19 January 2020.