Wildflowers of the Adirondacks:

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) is a low-growing wildflower with shiny evergreen leaves found in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. It bears small white flowers in July and August followed by bright red berries that often persist through winter.

- Wintergreen is a member of the Ericaceae (heath) family, a large family of flowering plants usually found in acid soil. This family includes a large number of plants that occur in the Adirondack Mountains, including Common Lowbush Blueberry, Highbush Blueberry, Small Cranberry, Trailing Arbutus, Bog Rosemary, Leatherleaf, Sheep Laurel, Bog Laurel, Indian Pipe, One-sided Wintergreen, Shinleaf, and Labrador Tea.

- Wintergreen is part of the Gaultheria genus, which also contains Creeping Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula), another low-growing plant that also can be found in the Adirondack region. The genus Gaultheria was named for Jean-François Gaultier, a naturalist and physician in Quebec in the mid-18th century.

- The species name (procumbens) apparently is derived from the Latin verb prōcumbō, which means to fall prostrate – a reference to the prostrate habit of the plant.

The common name (Wintergreen) is a reference to the evergreen leaves. Other common names include American Wintergreen, Boxberry, Checkerberry, Teaberry, Creeping Wintergreen, Deerberry, Eastern Spicy-wintergreen, Eastern Teaberry, Eastern Wintergreen, Ground Holly, Ground Tea, Mountain Tea, Mountain-tea, Redberry Wintergreen, Spiceberry, and Spicy Wintergreen.

Identification of Wintergreen

Wintergreen is classified as a shrub or sub-shrub. It is a low plant, growing from slender, creeping underground stems that form small colonies of plants. The branches arising from these stems are upright, about two to six inches high.

The branches bear leaves that are usually clustered towards the tips of the branches.

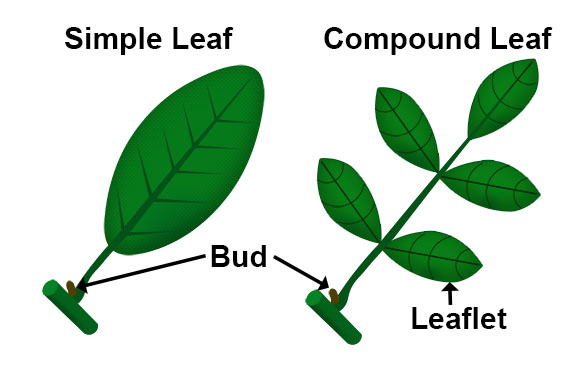

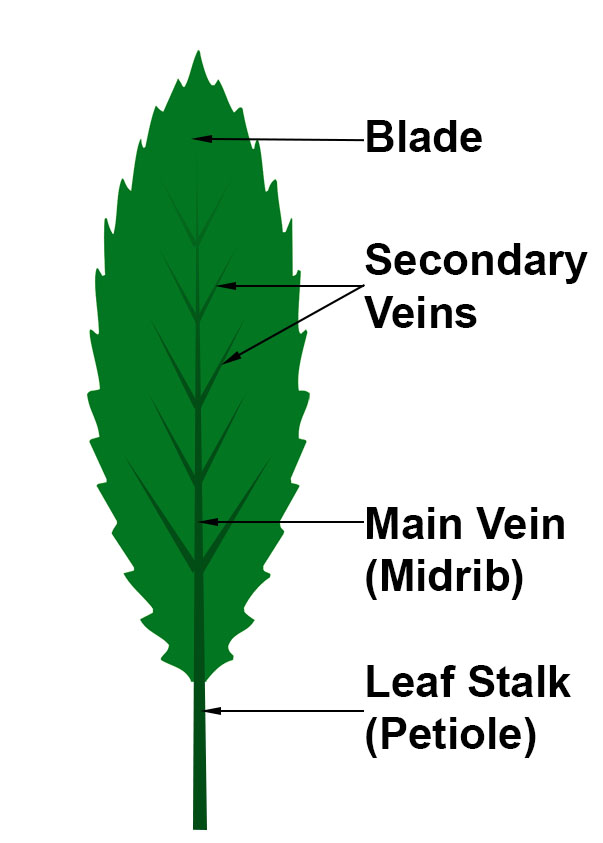

- The leaves of Wintergreen, which have a strong minty fragrance, are simple

Simple Leaf: A leaf with a single undivided blade, as opposed to a compound leaf, which is one that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets., which means that they are undivided, in contrast to compound leaves

Simple Leaf: A leaf with a single undivided blade, as opposed to a compound leaf, which is one that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets., which means that they are undivided, in contrast to compound leaves Compound Leaf: A leaf that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets. which have multiple parts.

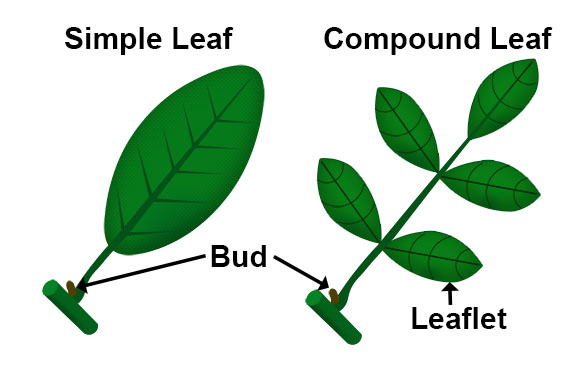

Compound Leaf: A leaf that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets. which have multiple parts. - The leaves are arranged

alternately

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem., meaning that they emerge from the stem one per node.

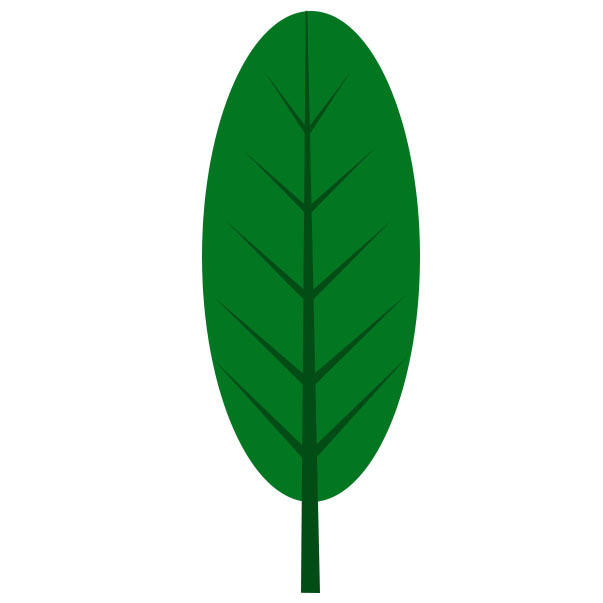

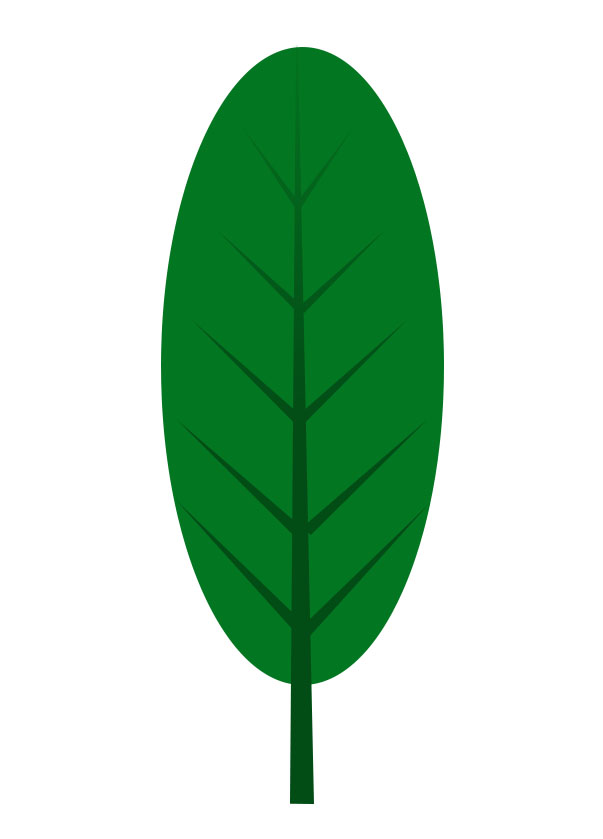

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem., meaning that they emerge from the stem one per node. - Wintergreen leaves are oval to elliptical

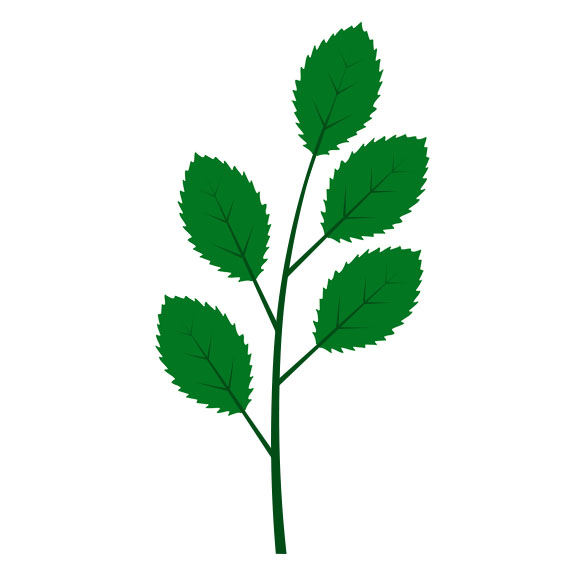

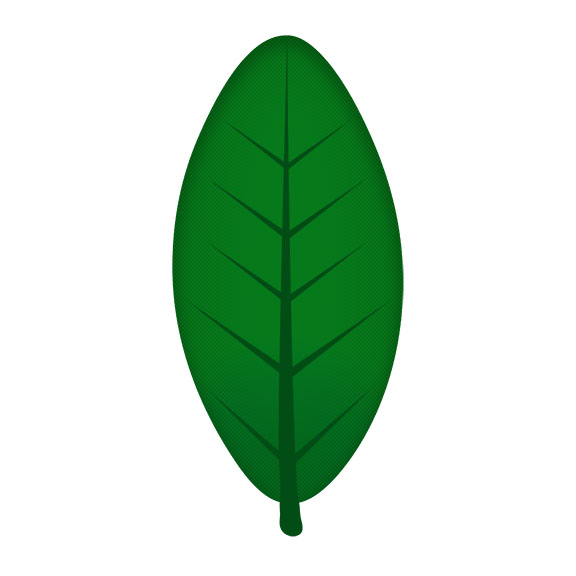

Elliptic: A leaf shaped like an ellipse, widest at the center and tapering at each end., about an inch or two long, with a short stalk. The upper surface is medium to dark green and very shiny. There are very fine teeth widely spaced around the edges, with a spine-like hair at the tip of each tooth.

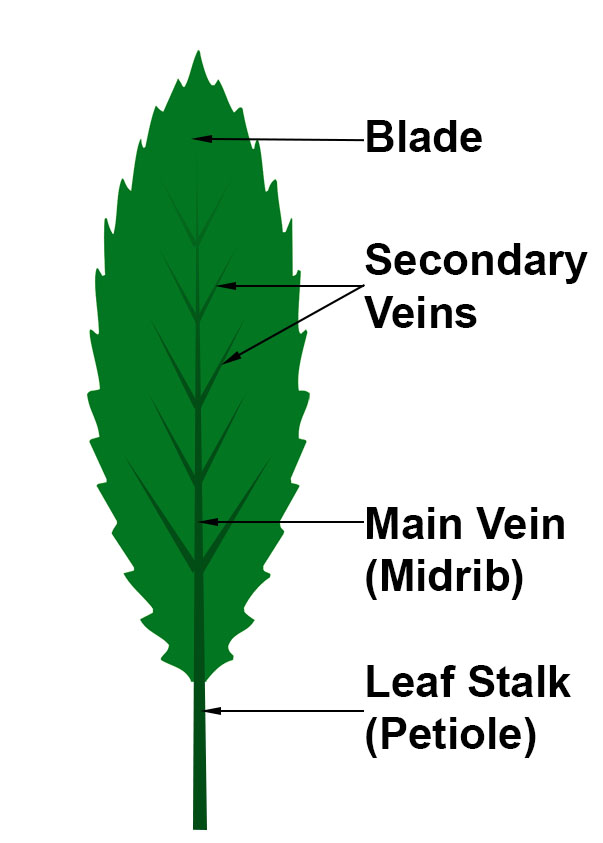

Elliptic: A leaf shaped like an ellipse, widest at the center and tapering at each end., about an inch or two long, with a short stalk. The upper surface is medium to dark green and very shiny. There are very fine teeth widely spaced around the edges, with a spine-like hair at the tip of each tooth. - The leaf blade

Blade: The broad, flat portion of a leaf, where photosynthesis occurs. has one main

vein

Blade: The broad, flat portion of a leaf, where photosynthesis occurs. has one main

vein Vein: A vessel that conducts nutrients, sugars, and other substances throughout plant tissues; usually associated with leaves. The arrangement of veins in a leaf is called the venation pattern.

running from the base towards the tip. Leaf venation is

pinnate

Vein: A vessel that conducts nutrients, sugars, and other substances throughout plant tissues; usually associated with leaves. The arrangement of veins in a leaf is called the venation pattern.

running from the base towards the tip. Leaf venation is

pinnate Pinnate Leaf Venation: A vein arrangement in a leaf with one main vein extending from the base to the tip of the leaf and smaller veins branching off the main vein., meaning that there are smaller veins branching off the main vein.

Pinnate Leaf Venation: A vein arrangement in a leaf with one main vein extending from the base to the tip of the leaf and smaller veins branching off the main vein., meaning that there are smaller veins branching off the main vein. - As the plant's common name implies, Wintergreen leaves are evergreen, persisting through winter. They sometimes turn reddish or burgundy as the weather turns colder.

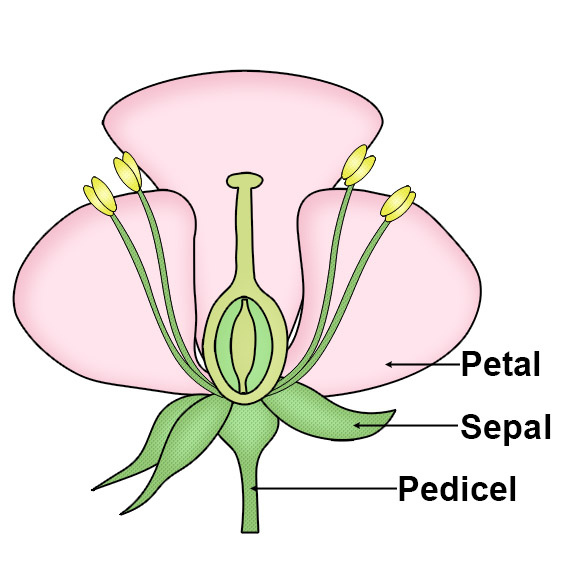

Wintergreen's nodding flowers dangle beneath its leaves.

- The flowers are waxy, white and tiny, ¼ to ½ inches long.

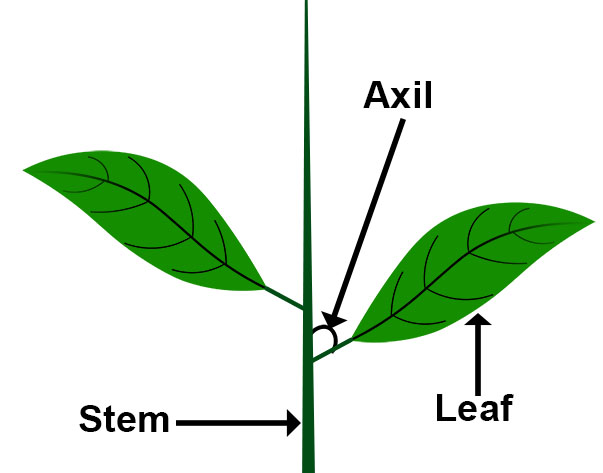

- The flowers are solitary or occur in groups of two or three. They dangle from the leaf axils

Axil: The angle between the upper side of a leaf or stem and the stem or branch that supports it..

Axil: The angle between the upper side of a leaf or stem and the stem or branch that supports it.. - The flowers are bell-shaped. The five white petals are fused with the tips curled back.

- The pedicel

Pedicel: the flower stalk which supports the flower.

(the stalk of the flower) is about ⅓ inch long and is light green to red.

Pedicel: the flower stalk which supports the flower.

(the stalk of the flower) is about ⅓ inch long and is light green to red.

In the Adirondack region, Wintergreen usually blooms beginning in mid-summer. A tally of bloom dates for the upland Adirondack areas compiled by Michael Kudish, based on data collected from the early seventies to the early nineties, lists the plant as in flower in August.

Recent data suggests that, depending on weather, buds may appear in areas within the Adirondack Park Blue Line in early July, followed by flowers in late July and August. Plants in areas just south of the Blue Line tend to flower a bit earlier, in early July.

Wintergreen's fertile flowers are replaced by fruit, which takes the form of small, berry-like capsules.

- The berries are initially a very light green (in late August and early September), usually maturing to bright red by around October.

- The berries are ¼ to ⅓ inches in diameter, with a strong flavor of wintergreen.

- Each berry has a distinctive notched pucker on its underside and contains many small seeds.

- The berries often persist throughout the winter (unless eaten by wildlife or passing humans) and are said to be larger and tastier in the spring than in autumn.

Wintergreen's bright red berries are about the same size and color as those of Partridgeberry, another low-growing evergreen plant found in the Adirondacks. Both are trailing, evergreen plants that produce white flowers in summer. In both cases, the berries persist through the winter. The flowers and leaves, however, are very different.

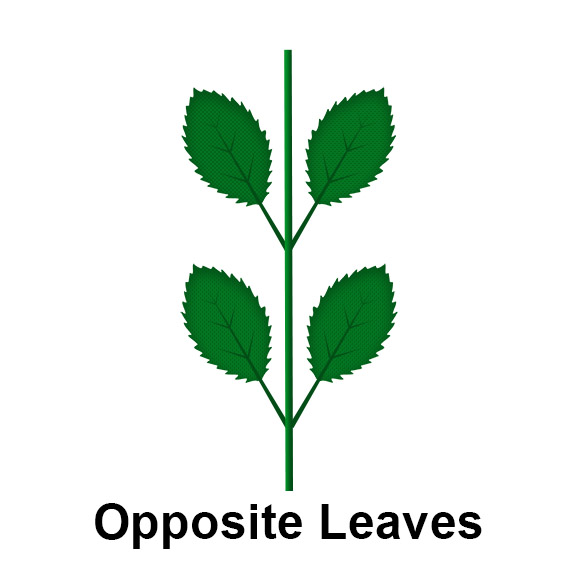

- Partridgeberry's leaves are opposite

Oppposite Leaves - leaves occurring in pairs at a node, with one leaf on either side of the stem. (meaning that there the leaves emerge from the stem in pairs), in contrast to Wintergreen's alternate leaves. Partridgberry's leaves are larger and wider in the middle than those of Wintergreen. Partridgeberry leaves are smooth

Oppposite Leaves - leaves occurring in pairs at a node, with one leaf on either side of the stem. (meaning that there the leaves emerge from the stem in pairs), in contrast to Wintergreen's alternate leaves. Partridgberry's leaves are larger and wider in the middle than those of Wintergreen. Partridgeberry leaves are smooth Smooth leaf edges do not have any teeth. (lacking the widely spaced teeth of Wintergreen), and they have a prominent whitish-yellow center vein

Smooth leaf edges do not have any teeth. (lacking the widely spaced teeth of Wintergreen), and they have a prominent whitish-yellow center vein Vein: A vessel that conducts nutrients, sugars, and other substances throughout plant tissues; usually associated with leaves. The arrangement of veins in a leaf is called the venation pattern.. In addition, Partridgeberry's leaves lack the distinctive fragrance of Wintergreen.

Vein: A vessel that conducts nutrients, sugars, and other substances throughout plant tissues; usually associated with leaves. The arrangement of veins in a leaf is called the venation pattern.. In addition, Partridgeberry's leaves lack the distinctive fragrance of Wintergreen. - Partridgeberry flowers are very different. They don't dangle like those of Wintergreen, but occur in pairs above the leaves. Partridgeberry flowers have four petal-like lobes, and the internal surfaces are covered with dense, white hairs, giving the flowers a fuzzy appearance.

Another low, trailing evergreen plant that grows in the Adirondacks is Creeping Snowberry. Like Wintergreen, this plant is a member of the Gaultheria genus.

- Creeping Snowberry is a much smaller plant than Wintergreen. As with Wintergreen, Creeping Snowberry's leaves are alternate, but they are egg-shaped and much smaller, generally less than ⅜

inches in length, with smooth margins

Smooth leaf edges do not have any teeth. (in contrast to Wintergreen's hair-tipped teeth).

Also, they lack the minty aroma of Wintergreen leaves.

Smooth leaf edges do not have any teeth. (in contrast to Wintergreen's hair-tipped teeth).

Also, they lack the minty aroma of Wintergreen leaves. - Creeping Snowberry's tiny white flowers also hang below the leaves, but they appear in spring, rather than summer.

- Creeping Snowberry develops small, white berries that contrast with Wintergreen's bright red fruit.

- Creeping Snowberry is often found in much moister sites, such as the edges of bogs.

Uses of Wintergreen

Wintergreen has a variety of uses as a food.

- Wintergreen's mint-flavored berries are edible and have been used to make pies or jams. Wintergreen berries were consumed by several native American groups. The Iroquois, in instance, mashed the fruit, made it into small cakes, and dried the cakes for future use.

- The leaves of the plant were used to make oil of wintergreen to flavor candies, medicines, and chewing gum. Several sources caution that large doses of wintergreen oil can be toxic. The leaves were also used to make tea by several native Americans groups, including the the Algonquin, Chippewa, Ojibwa, and Cherokee.

Wintergreen was also widely used for its medicinal properties. Native Americans used the plant to treat a variety of ailments, including colds, headaches, stomach aches, chronic indigestion, kidney disorders, and rheumatism. The Iroquois, for instance, used a compound infusion of Wintergreen roots as for tape worms; they took a decoction of the leaves to treat colds. The Mohegans used an infusion of the plant as a kidney medicine. Poultices of crushed Wintergreen leaves were also applied externally on wounds, rashes, and bruises.

Wildlife Value of Wintergreen

Wintergreen's value as a food for wildlife depends, as with all plants, on its availability and the availability of alternative foods. Wintergreen is not taken in large quantities by any species of wildlife, but its value is enhanced by the fact that both its berries and leaves persist through winter.

Several species of birds consume Wintergreen, including Wild Turkey and Ring-necked Pheasant. Ruffed Grouse consume Wintergreen's fruit, buds, and leaves. For instance, a study of the diet of Ruffed Grouse in Maine found that Wintergreen constituted 2.2% of the total volume of its annual diet, with higher percentages in autumn.

White-tailed Deer browse Wintergreen throughout its range. The plant constitutes 5-10% of the White-tailed Deer's diet. In some localities, Wintergreen is an important winter food. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation lists Wintergreen as a preferred winter deer food, based on observations in deer wintering areas over many years from all parts of New York State.

Other animals that eat wintergreen are American Black Bears (which consume the fruit, constituting up to 2% of their diet in some areas), White-footed Mice, Deer Mice, Red Squirrels, and Red Foxes. Wintergreen is also reported to be a favorite food of the Eastern Chipmunk.

Wintergreen's importance for insects is relatively low. The primary pollinators of Wintergreen are bumblebees. Other insects which feed on the sap or foliage include one species of aphids and one species of moth larvae.

Distribution of Wintergreen

Wintergreen occurs in the eastern half of the United States and the southern provinces of Canada. It can be found from Newfoundland and New England south in the mountains to Georgia and west to Minnesota. This plant is listed as Endangered in Illinois.

Wintergreen grows in nearly all counties in New York State and all Adirondack Park Blue Line counties

Habitat of Wintergreen

Wintergreen is adapted to coarse and medium-textured soil. It has low fertility requirements and prefers acidic soils. It is tolerant of shade, but grows and flowers best in semi-open sites, with partial sun to light shade. It prefers fairly well-drained soils, but can tolerate wetter sites.

Wintergreen can be found in a variety of habitats, including acidic hardwood forests and hemlock-hardwood forests, often in close proximity to other plants that need infertile or acidic soil. This plant is classified as Facultative Upland (FACU), which means that it usually occurs in uplands (non-wetlands), but may occur in wetlands.

In the Adirondack Mountains, Wintergreen is found in a variety of ecological communities, including:

Look for Wintergreen growing along many of the trails covered here, including the Bloomingdale Bog Trail and Peninsula Nature Trails, as well as the Barnum Brook Trail, Boreal Life Trail, and Heron Marsh Trail at the Paul Smith's College VIC.

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 143.

Michael Kudish. Paul Smiths Flora II: Additional Vascular Plants; Bryophytes (Mosses and Liverworts); Soils and Vegetation; Local Forest History (Paul Smith's College, 1981), p 56.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Wintergreen. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

J. T. Kartesz. The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2015. Taxonomic Data Center. Chapel Hill, N.C. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Eastern Teaberry. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Flora of North America. Gaultheria procumbens Linnaeus. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

NatureServe Explorer. Online Encyclopedia of Life. Gaultheria procumbens - L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Margaret B. Gargiullo. A Guide to Native Plants of the New York City Region (New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, 2007), p. 97.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Gaultheria Procumbens. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Gaultheria Hispidula. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Mitchella Repens. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

New England Wildflower Society. Go Botany. Eastern Spicy-wintergreen. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 95-96, 101-102, 102-103, 108-109, 109, 117, 118, 121-122. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Chestnut Oak Forest. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Heath Barrens. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Oak-Heath Rocky Summit. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Red Pine Rocky Summit. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Sandstone Pavement Barrens. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

USA National Phenology Network. Nature’s Notebook. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Wintergreen. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Gaultheria procumbens (Wintergreen). Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Wintergreen. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Vertebrate Animal & Plant Database. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Insect Visitors of Illinois Wildflowers. Flower-Visiting Insects of Checkerberry. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Plant-Feeding Insect Database. Gaultheria spp. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Winter Deer Foods. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

iNaturalist. American wintergreen. Gaultheria procumbens. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

Anne McGrath. Wildflowers of the Adirondacks (EarthWords, 2000), p. 21, Plate 10.

Roger Tory Peterson and Margaret McKenny. A Field Guide to Wildflowers. Northeastern and North-central North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1968), pp. 38-39.

Doug Ladd. North Woods Wildflowers (Falcon Publishing, 2001), p. 184.

Lawrence Newcomb. Newcomb's Wildflower Guide (Little Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 212-213.

David M. Brandenburg. Field Guide to Wildflowers of North America (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2010), p. 217.

Timothy Coffey. The History and Folklore of North American Wildflowers (FactsOnFile, 1993), pp. 91-92.

Ruth Schottman. Trailside Notes. A Naturalist's Companion to Adirondack Plants (Adirondack Mountain Club, 1998), pp. 134-137.

William Carey Grimm. The Illustrated Book of Wildflowers and Shrubs (Stackpole Books, 1993), pp. 200-201, 550-551.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Wildflowers. Eastern Region. (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), p. 508, Plate 69.

William K. Chapman et al. Wildflowers of New York in Color (Syracuse University Press, 1998), pp. 36-37.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), p. 353.

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Stackpole Books, 1992), pp. 204-205.

John Eastman, "Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus)," The Eastman Guide to Birds: Natural History Accounts for 150 North American Species. Kindle Edition. (Stackpole Books, 2012).

Plants for a Future. Gaultheria procumbens - L. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America. Second Edition. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000), pp. 30-31.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Revised and Updated. (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 262-263.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Medicinal Wild Plants. Revised and Updated. Second Edition, (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 238-239.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Eastern Teaberry. Gaultheria procumbens L. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Allen J. Coombes. Dictionary of Plant Names (Timber Press, 1994), p. 78.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899), p. 112. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

An Adirondack Naturalist in Illinois. Another Day on the Trails. 27 August 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

Saratoga Woods and Waterways. Scrambling Around the River's Rocks, Part II. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

Saratoga Woods and Waterways. Woods Hollow Habitat: Good for Goodyera. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

Saratoga Woods and Waterways. Archer Vly -- A Second Lake Desolation Destination. 30 July 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

W. J. Bennetts, "Notes on the Food of the Ruffed Grouse," Bulletin of the Wisconsin Natural History Society, Volume 1, Number 2 (April 1900), pp, 105-110. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

Charles P. Brown, "Food of Maine Ruffed Grouse by Seasons and Cover Types," The Journal of Wildlife Management, Volume 10, Number 1 (January 1946), pp. 17-28. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

N. W. Hosley and R. K. Ziebarth, "Some Winter Relations of the White-Tailed Deer to the Forests in North Central Massachusetts," Ecology, Volume 16, Number 4 (October 1935), pp. 535-553. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

William Richard Van Dersal. Native Woody Plants of the United States: Their Erosion-control and Wildlife Values (US Department of Agriculture, 1938), p. 134. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

Bernard Boivin, “Gaultier, Jean-François,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1974. Retrieved 26 February 2018.