Wildflowers of the Adirondacks:

Creeping Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula)

Creeping Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula) is a low, trailing evergreen plant found near bogs, other wetlands, and moist forests in the Adirondacks. It is a member of the Heath Family.

The Heath (Ericaceae) Family includes a number of other flowering plants found in the Adirondack Park, including Bog Rosemary, Leatherleaf, Trailing Arbutus, Sheep Laurel, Bog Laurel, One-flowered Wintergreen, Shinleaf, and Labrador Tea.

Creeping Snowberry is part of the genus Gaultheria, which was named for Jean-François Gaultier, a naturalist and physician in Quebec in the mid-18th century. The other species in this genus that is found in the Adirondacks is Wintergreen.

- Creeping Snowberry's species name (hispidula) means "finely bristled," and is a reference to the bristles on the stem and leaves.

- The nonscientific name is a reference to the small, white berries that appear in late summer. The plant is also known as Moxie Plum, apparently a reference to the Algonquian word for medicine, and Creeping Spicy-wintergreen.

Identification of Creeping Snowberry

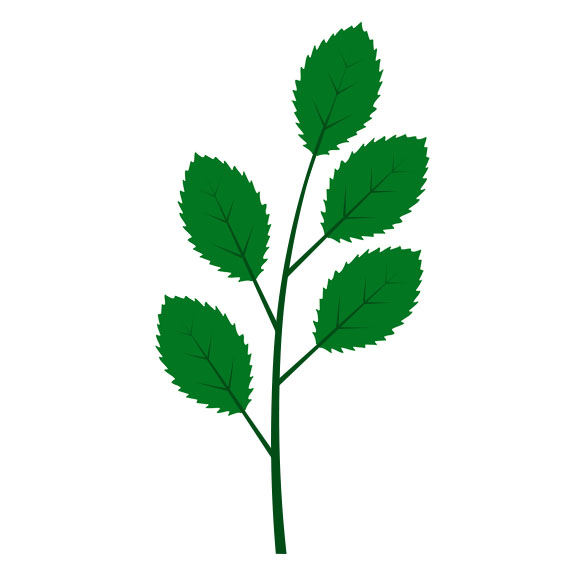

This attractive little plant is a low-growing, mat-like, evergreen shrub. The creeping stems, which are covered with brown bristles, form leafy mats on logs and hummocks, often near Sphagnum moss. The leaves and berries of this plant taste and smell like wintergreen.

The plant may be recognized in any season by its growing habit and its leaves.

- The tiny dark green, evergreen leaves are alternately arranged

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem., meaning that a single leaf is attached at a node.

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem., meaning that a single leaf is attached at a node. - The leaves are egg-shaped or rounded, very short-stalked, hairless above and with scattered brownish hairs below. They are generally less than ⅜ inch in length.

- The leaf marginsThe structure of the leaf's edge. (edges) are smooth, meaning that the leaves do not have teeth

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge.. The leaf blade

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge.. The leaf blade.jpg) The flat portion of a leaf, petal, or sepal. has bristly hairs, which grow flat in the same plane as the leaf surface, pointing toward the tip of the leaf.

The flat portion of a leaf, petal, or sepal. has bristly hairs, which grow flat in the same plane as the leaf surface, pointing toward the tip of the leaf. - The underside of the leaf is a lighter green.

The pale white flowers appear in spring, usually in late May in the Adirondacks. The four-parted flowers are small and bell-shaped. The flowers are about ⅛ inch or less across. They hang along the undersides of the running stems and are usually hidden beneath the leaves.

The flowers are followed by fruit, which is the source of this plant's common name. The berries are white and egg-shaped, about ¼ inch in diameter. Berries are often hidden among the small leaves.

The berries, which are said to be edible, ripen in mid- to late summer. In the Adirondack region, the berries usually appear in late July or early August.

Uses of Creeping Snowberry

Creeping Snowberry fruits reportedly are edible. The berries are sometimes eaten fresh, with cream and sugar. They can also be made into a preserve. The berries are said to be pleasantly acid, with a wintergreen flavor. The leaves are also said to be edible. They can be eaten raw or cooked or used to make a tea.

The plant has limited medicinal uses. Native Americans used it to some extent. For instance, the Algonquin used an infusion of leaves as a tonic for overeating. They also consumed the fruit. The Chippewa used the leaves to make a beverage. The Anticosti used the plant as a sedative to facilitate sleep.

Wildlife Value of Creeping Snowberry

Creeping Snowberry has limited wildlife value. This species is pollinated by solitary bees, bumblebees, bee-flies, and hover flies. The berries are eaten by chipmunks and deer mice. Creeping Snowberry is a host plant for the Bog Fritillary.

Distribution of Creeping Snowberry

Creeping snowberry is distributed in the boreal region of North America from Labrador, west to British Columbia and south into the northern United States. It can be found in the northeastern United States, west to Minnesota and Wisconsin. Creeping Snowberry is rare at the southern end of its range.

This plant is listed as threatened in Connecticut and Rhode Island, as endangered in Maryland and New Jersey, rare in Pennsylvania, and sensitive in Washington. It is presumed extirpated in Ohio.

In New York State, its presence has been documented in most counties in the eastern part of the state. Creeping Snowberry occurs in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line.

Habitat of Creeping Snowberry

Creeping Snowberry is classified as a Facultative Wetland plant (FACW), meaning that it usually occur in wetlands, but may occur in non-wetlands. It grows in acidic and neutral soils. It can grow in well- or poorly drained soils. It is shade-tolerant.

In New York State, Creeping Snowberry is often found growing on hummocks in cool swamps or on mossy sites in cool mixed or coniferous forests. It is sometimes found on rotting logs or stumps. In the Adirondack Park, Creeping Snowberry is found in several ecological communities:

Look for Creeping Snowberry on the edges of bogs. A convenient place to observe this species is near the Barnum Pond Overlook on the Boreal Life Trail, where it forms a dense mat, creating a miniature landscape. Creeping Snowberry also grows on the bog at the Silver Lake Bog Preserve, where it can be seen from the boardwalk. You can also find Creeping Snowberry at higher elevations, in alpine zones of Adirondack high peaks.

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 143.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Snowberry. Gaultheria hispidula (L.) Muhl. ex Bigelow. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Ericaceae. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Gaultheria. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Creeping Snowberry. Gaultheria hispidula (L.) Muhl. ex Bigelow. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. Plant of the Week. Creeping Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula). Retrieved 25 March 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Conservation Assessment for Creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula). US Forest Service, 2001, pp. 7-8.

Flora of North America. Gaultheria hispidula (Linnaeus) Muhlenberg ex Bigelow. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Gaultheria Procumbens. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Gaultheria Hispidula. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Mitchella Repens. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Creeping Spicy-wintergreen. Gaultheria hispidula. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 61, 72, 74-75, 76, 106-107, 122, 122-123. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Alpine Sliding Fen. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Balsam Flats. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Ice Cave Talus Community. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Northern White Cedar Swamp. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce-Fir Swamp. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 23. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Gaultheria hispidula (L.) Muhl. ex Bigelow. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Gaultheria hispidula. Creeping Snowberry. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Gaultheria hispidula. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Creeping Snowberry. Gaultheria hispidula. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

Lawrence Newcomb. Newcomb's Wildflower Guide (Little Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 128-129.

Ronald B. Davis. Bogs & Fens. A Guide to the Peatland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 126-127.

David M. Brandenburg. Field Guide to Wildflowers of North America (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2010), p. 217.

Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. Butterflies of Canada. Bog Fritillary. (Boloria eunomia). Retrieved 25 March 2017.

Plants for a Future. Gaultheria hispidula - (L.) Muhl. ex Bigelow. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

Lee Allen Peterson. A Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977), pp. 222-223.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Gaultheria hispidula. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

Doug Ladd, North Woods Wildflowers (Falcon Publishing, 2001), p. 183.

Roger Tory Peterson and Margaret McKenny. A Field Guide to Wildflowers. Northeastern and North-central North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1968), pp. 38-39.

Nancy G. Slack and Allison W. Bell. Adirondack Alpine Summits: An Ecological Field Guide (Adirondack Mountain Club, Inc., 2006), p. 25.

Allen J. Coombes. Dictionary of Plant Names (Timber Press, 1994), p. 78.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba. (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899), p. 112. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Bernard Boivin, “Gaultier, Jean-François,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1974. Retrieved 26 February 2018.