Adirondack Ferns

Ferns are nonflowering vascular plants that flourish in a variety of habitats in the Adirondack Park.

- Like other vascular plants, ferns have certain tissue that conducts water and nutrients. They have branched stems and leaves like other vascular plants. This sets them apart from non-vascular plants, such as moss and liverworts. The vascular tissue in ferns is what allowed them to grow up and out rather than just spreading along the ground.

- Like moss, ferns are spore-bearing plants, which means that they reproduce from spores instead of seeds. This sets them apart from seed plants, a group which includes both gymnosperms (such as conifers) and angiosperms (flowering plants).

Some ferns, such as the Christmas Fern and Intermediate Wood Fern, are evergreen, and can be found all year. Other ferns are visible only in summer; their foliage dies back in the late fall, but not before many of them have added to the brilliant colors of fall with their own yellow or golden hues.

List of Adirondack Ferns

The Role of Ferns in Adirondack Ecological Communities

Ferns can be found in a variety of habitats in the Adirondack region. Many of our ferns flourish in wetlands, such as swamps, marshes, and stream banks. Others prefer well-drained soils. Some of these prefer rich mesic hardwood forests. Some are more commonly found in mixed wood forests. Shade tolerance also varies. Lady Fern, for instance, is shade tolerant, while the Eastern Bracken Fern is shade intolerant. Hay-scented Fern is mid-tolerant, doing best where there is at least some sun.

Ferns play an important role in ecological succession. After a severe fire, shade-intolerant ferns (such as Eastern Bracken Fern) are among the first plants to colonize a site after a severe fire that wipes out most of the plants. in that area. Ferns are also pioneers following logging operations, sometimes retarding the succession of tree species.

Identifying Ferns

One of the first steps in identifying a fern (or any other plant, for that matter) is to note where it's growing. While some ferns (such as Spinulose Wood Fern) grow under a wide variety of conditions, others have more restrictive requirements in terms of sunlight, soil moisture, and habitat. Noting these characteristics of the site can be a quick way of excluding a number of ferns from consideration.

- Is your mystery fern growing in full sun, shade, or partial shade? Some shade-intolerant ferns, such as Eastern Bracken Fern, are usually found growing on sunny sites, while shade-tolerant ferns, such as Christmas Fern, are more commonly seen on shaded sites.

- How wet is the soil? Some ferns thrive primarily in wet soils. If you are walking an Adirondack trail and observe a fern thriving on a very poorly drained site, Cinnamon Fern or Royal Fern would be among your first suspects.

- What's the habitat like? Is the fern growing in a northern hardwood forest, mixed wood forest, or conifer forest? Some ferns, like the Maidenhair Fern, are commonly found in hardwood forests, often under Sugar Maple.

After you have narrowed down the list of potential suspects based on site characteristics, you can turn to the physical characteristics of the fern itself.

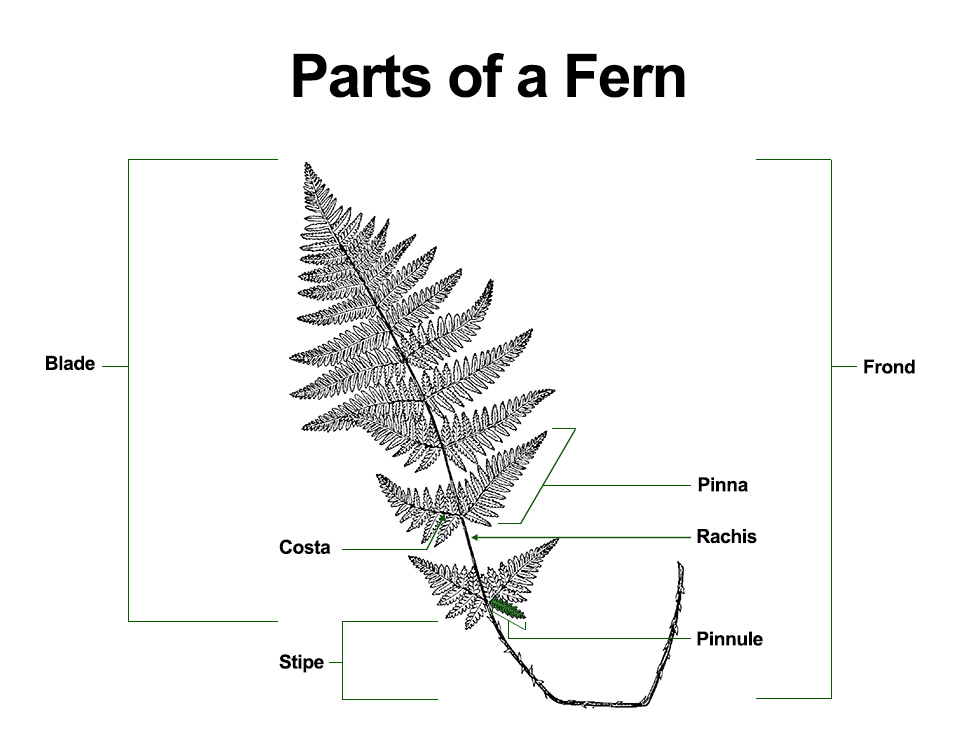

- Frond: The whole, visible fern leaf. (This is referred to as the leaf in some guide books.) Fronds can be fertile or sterile. Fertile fronds have spore cases (called sporangia) that are usually grouped into clusters called sori on the back of the frond; sterile fronds do not. In some cases, such as the Sensitive Fern, Cinnamon Fern and Interrupted Fern, the fertile fronds and the sterile fronds are quite different in appearance, providing important clues to the plant's identity.

- Blade: The leafy part of the frond. Blade shapes vary widely, from the simple, undivided forms characteristic of ferns such as the Sensitive Fern to the complex, lacy forms of the Intermediate Wood Fern. Some ferns have broad-based blades, while others have tapering blades.

- Pinna: A primary division of the blade. This is referred to as the leaflet in some guide books. The margins (edges) of the pinna may be smooth, toothed, or lobed.

- Pinnule: A subdivision of the pinna. (This is referred to as the sub-leaflet in some guide books.) In some species, pinnules are also divided.

- Costa: The midvein of the pinna.

- Rachis: The stalk within the blade. The color and texture of the rachis (pronounced ray-kiss) varies with the species.

- Stipe: The stalk below the blade. The stipe can be different colors and is diagnostic for some species.

Other keys to a fern's identity include the fern's growth form (i.e., prostrate or upright) and the arrangement of the sori (fruit dots or clusters of spore cases).

Some Common Adirondack Ferns

Some Common Ferns of the Adirondack Park

- Christmas Fern (Polystichum acrostichoides)

- Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum)

- Eastern Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum)

- Hay-scented Fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula)

- Intermediate Wood Fern (Dryopteris intermedia)

- Interrupted Fern (Osmunda claytoniana)

- Long Beech Fern (Phegopteris connectilis)

- New York Fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis)

- Maidenhair Fern (Adiantum pedatum)

- Marginal Wood Fern (Dryopteris marginalis)

- Northern Lady Fern (Athyrium angustum)

- Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis)

- Sensitive Fern (Onoclea sensibilis)

- Spinulose Wood Fern (Dryopteris carthusiana)

There are about 12,000 species of ferns worldwide, but only about 100 occur in northeastern and central North America and about 60 in the Adirondack Mountains. The ferns most frequently encountered along the trails in our region include Spinulose Wood Fern, Eastern Bracken Fern, Sensitive Fern, Cinnamon Fern, Royal Fern, Interrupted Fern, Hay-scented Fern, New York Fern, Maidenhair Fern, Marginal Wood Fern, and Northern Lady Fern.

Spinulose Wood Fern (Dryopteris carthusiana) is one of the commonest ferns encountered along Adirondack trails. This fern is a medium to large fern, with a lacy appearance. The spores are located on the underside of the frond. The spore-bearing fronts are similar in size and shape to the sterile fronds.

Spinulose Wood Fern, which tends to grow in clumps, can be found growing on a wide variety of soils and in a wide variety of habitats, including swamps, wet forests, and stream banks. It can also be found in mesic to dry-mesic pine forests and occasionally in mesic hardwood forests. It is shade-tolerant. In the northern part of its range, the ferns are deciduous, while in the southern part of its range they are evergreen. Some sources indicate that the fertile fronds are deciduous, while the sterile fronds may stay green into winter.

Hay-scented Ferns (Dennstaedtia punctilobula) are very common in the Adirondacks and, in fact, grow throughout New York State and eastern North America. The common name derives from the strong aroma of crushed hay, which the fronds give out in late summer. The Hay-scented Fern is one of only three fern species that are not protected by law in New York State. (The others are Sensitive Fern and Eastern Bracken Fern.) The Hay-scented Fern is also called Eastern Hay-scented Fern and Boulder Fern.

The Hay-scented Fern, which often grows in large patches, is a yellowish green fern. Its fronds are dainty and lacy in appearance, with long tapered tips. Hay-scented Ferns grow in successional fern meadows (a meadow that occurs on sites cleared for logging or farming or disturbed by fire), such as the Brandon Burn in Franklin County near Paul Smiths. You can also find Hay-scented Ferns in northern hardwood forests and mixed wood forests where there are gaps in the canopy, fields with thin acidic soils, thickets, blueberry barrens, and logging roads – sites where they can get at least some sun.

Eastern Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum) is a member of the same family as Hay-scented Fern and, like the latter, is a persistent pioneer plant, frequently gaining dominance after logging or burns. Eastern Bracken Fern is easy to recognize, because of its large, triangular fronds. It is a relatively large fern, usually growing about waist high. Eastern Bracken Fern is deciduous. In northern climates, the fronds die back in winter; new fronds emerge in early spring. Fronds begin to change color in late summer, turning in some cases an unattractive dull brown and in others a striking gold.

Eastern Bracken Fern thrives in a wide variety of soils and habitats and is common throughout the northeast, including the Adirondack Park It does best in full sunlight on well-drained soils, but can also grow in semi-shaded areas and thickets. It can be found in hardwood or pine forests, woodland edges, old fields, thickets, and under power lines. Although this fern usually occurs in non-wetlands, it can occasionally be found in wetlands.

Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum) is a deciduous fern that grows in wet areas throughout the Adirondack Mountains and New York State. The common name derives from cinnamon-brown color of the fertile fronds. The Cinnamon Fern produces separate fertile and sterile fronds. The fertile fronds, which are shorter, are the first to appear in the spring, initially as bright green wands, then turning a deep cinnamon brown. The green, arching sterile ferns are longer (20-60 inches). The pinnae (leaflets) on sterile fronds are large and narrow gradually to the tip.

Cinnamon Ferns are widely distributed in the eastern half of the US and the southern provinces of Canada, occurring from Newfoundland to western Ontario and south to the Gulf States and New Mexico. Cinnamon Ferns are found in all New York counties and are present in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line. Cinnamon Ferns prefer wet acidic soil and shady to partially shady sites. Although this plant occasionally occurs in non-wetlands, Cinnamon Ferns are usually found in poorly drained sites in our area. Look for them in swamps, marshes, and wet forests. Ecological communities where Cinnamon Ferns can be found in the Adirondack region include Hemlock-Hardwood Swamps , Northern White Cedar Swamps, and Black Spruce-Tamarack Bogs.

Sensitive Fern (Onoclea sensibilis L.) is a native fern that grows primarily in wetlands and wet forests in the Adirondack Mountains and New York State. The common name derives from the fact that the fern is very sensitive to cold weather; the sterile fronds brown and wither with the coming of winter. This fern is also called Bead Fern – a reference to the beaded leaflets on its fertile fronds.

The Sensitive Fern has broad, almost triangular fronds, which contrast with the lacy appearance of many ferns. The sterile leaves are yellow-green to pale green, triangular, and up to 40 inches tall. They turn brown and die back after the first frost. The leaflets (pinnae) have a prominent network of veins. The edges (margins) are wavy. The fertile (spore-bearing) fronds are much shorter (about a foot tall). The early growth is green, with lobed, opposite leaflets, maturing to dark brown, beaded leaflets which persist through winter for several seasons.

The range of the Sensitive Fern includes eastern North America, as well as the southern provinces of Canada. This fern can be found in nearly all counties of New York State; it is common throughout the Adirondack Mountains. Sensitive Ferns prefer poorly drained areas, including swamps, marshes, wet fields, moist woods, and sites bordering boggy areas. Moderately shade-tolerant, this fern seems to do best in full sun, but will also grow in shade, in neutral to acid soil.

List of Adirondack Ferns

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992).

Boughton Cobb. A Field Guide to Ferns and their Related Families. Northeastern and Central North America. Second Edition (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005).

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Flora of North America. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Michael Burgess. A Field Guide to the Ferns of New England and Adjacent New York. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

Richard Mitchell. Atlas of New York State Ferns (New York State Museum, 1984). Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Eugene C. Ogden. Field Guide to Northeastern Ferns (New York State Museum, 1981). Retrieved 15 February 2017.

William J. Cody and Donald M. Britton. Ferns and Fern Allies of Canada (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1989). Retrieved 19 February 2017.

William J. Cody. Ferns of the Ottawa District (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1978). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

David B. Lellinger. A Field Manual of the Ferns & Fern Allies of the United States and Canada (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985).

Steve W. Chadde. Northeast Ferns: A Field Guide to the Ferns and Fern Relatives of the Northeastern United States (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013).

George Henry Tilton. The Fern Lover's Companion. A Guide for the Northeastern States and Canada (Little, Brown, 1923). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

Anne C. Hallowell and Barbara G. Hallowell. Fern Finder. A Guide to Native Ferns of Central and Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada. Second Edition. (Nature Study Guild Publishers, 2001).

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014). Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. Community Guides. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Quick Guide to the Common Ferns of New England. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

Minnesota Wildflowers. A Field Guide to the Flora of Minnesota. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Grasses, Sedges, & Non-Flowering Plants. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden. Ferns of the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Native Plant Guide. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Meiyin Wu & Dennis Kalma. Wetland Plants of the Adirondacks: Ferns, Woody Plants, and Graminoids (Trafford Publishing, 2011).

Ronald B. Davis. Bogs & Fens. A Guide to the Peatland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 242-249.

Gary Wade et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Spinulose Wood Fern. Dryopteris carthusiana. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014).

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Second Edition (Stackpole Books, 2008).

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Retrieved 19 February 2017.