Ferns of the Adirondacks:

Eastern Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Eastern Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum) is a coarse, deciduous fern with large, triangular fronds, growing about waist high. It thrives in old fields, mixed woods, and sunny trail sides throughout the Adirondack Park, often gaining dominance after logging or fire.

The Eastern Bracken Fern, like the Hay-scented Fern, is a member of the Dennstaedtiaceae Family. Eastern Bracken Fern is part of the Pteridium genus.

- The New York Flora Atlas lists two members of this genus: Eastern Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum) and Southeastern Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum ssp. pseudocaudatum). The latter fern does not occur in the Adirondack region; it is found only on Staten Island and eastern Long Island.

- The genus name (Pteridium) reportedly comes from the Greek pteron (wing); the fronds of ferns are said to suggest the wings of a bird.

- The species name (aquilinum) reportedly is a reference to the appearance of the fiddleheadFiddlehead: The unfurling young frond of true ferns, which loosely resembles the ornate, curled end of a fiddle. (Synonym=crosier), which as it unfolds looks like an eagle's claw. Other sources contend, however, that the name derives from the root of the Bracken or the stem near the base, which (when cut across) is said to resemble an eagle.

Other common names for this fern include: Bracken, Common Bracken, Bracken Fern, Brake Fern, Brackenfern, Northern Bracken Fern, Western Brackenfern, Eastern Brackenfern, and Eagle Fern. The latter name is another reference to the similarity of the fiddlehead to an eagle's claw.

The Eastern Bracken Fern is one of only three ferns that are not protected in New York State. The others are the Hay-scented Fern and the Sensitive Fern.

Identification of Eastern Bracken Fern

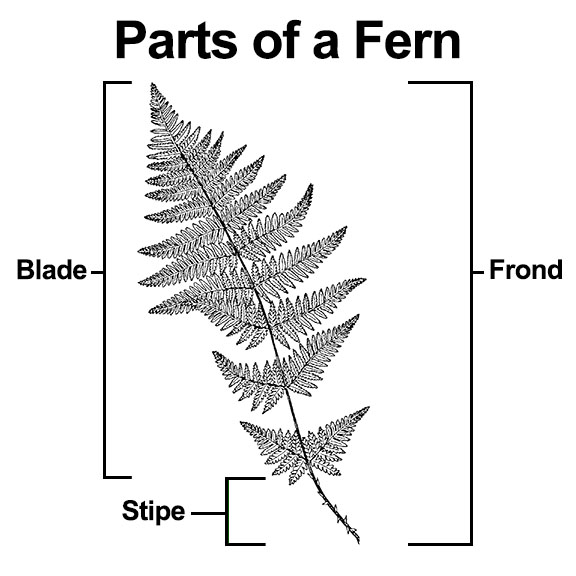

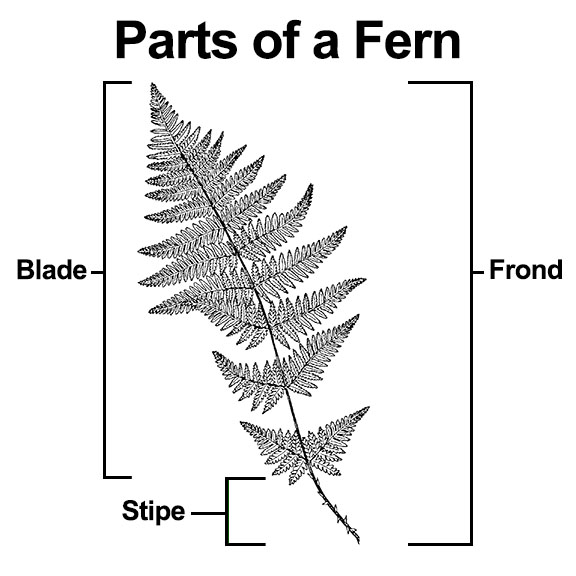

Eastern Bracken Fern is easy to recognize, because of its large, broadly triangular fronds Frond: The whole leaf of a fern. It includes the blade (the expanded leafy part of the frond) and the stipe (the stalk below the blade).. It usually grows about waist high.

Frond: The whole leaf of a fern. It includes the blade (the expanded leafy part of the frond) and the stipe (the stalk below the blade).. It usually grows about waist high.

- This fern grows from very long, creeping rhizomes

Rhizome: The modified subterranean stem of a plant that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks., which lie deep within the soil, protected from fire and drought.

Rhizome: The modified subterranean stem of a plant that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks., which lie deep within the soil, protected from fire and drought. - The blades

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond. (leaves) of the fronds grow almost horizontally, especially in more shady locations, forming a dense growth.

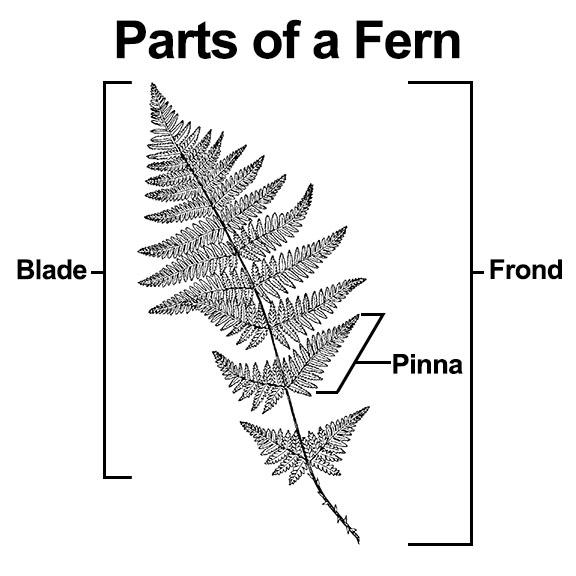

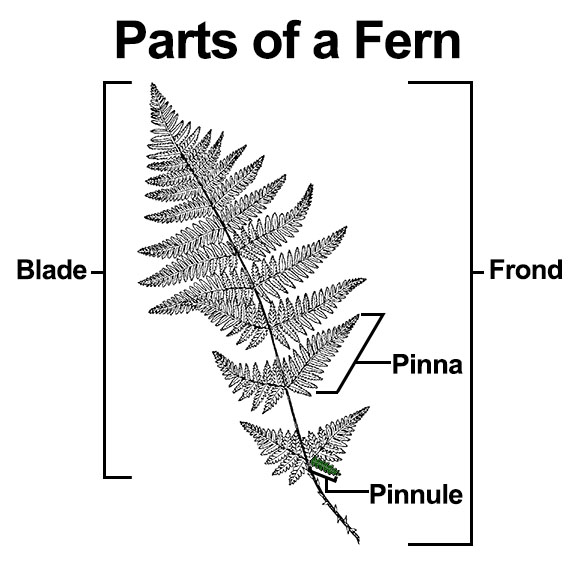

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond. (leaves) of the fronds grow almost horizontally, especially in more shady locations, forming a dense growth. - The blades are divided into pinnae

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). (leaflets), giving the impression of a three-part leaf. The pinnae are divided into pinnules

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). (leaflets), giving the impression of a three-part leaf. The pinnae are divided into pinnules Pinnule: A division of the pinna. (sub-leaflets), which are oblong with smooth

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. (sub-leaflets), which are oblong with smooth Smooth: Refers to the margin (edge) of a pinna or pinnule which is smooth, lacking teeth. (untoothed) edges.

Smooth: Refers to the margin (edge) of a pinna or pinnule which is smooth, lacking teeth. (untoothed) edges. - In contrast to ferns such as the Sensitive Fern, Interrupted Fern, and Cinnamon Fern (all of which also grow in the Adirondacks), the sterile frondsSterile frond: A frond without sporangia (spore cases). of the Eastern Bracken Fern are quite similar in appearance to the fertile frondsFertile frond: A frond with sporangia (spore cases).. On the fertile fronds, the soriSorus: A cluster of sporangia, usually borne on the underside or margins of the pinnae or pinnules. (plural = sori) (clusters of sporangiaSporangium: Spore cases inside which the spores develop. (plural = sporangia) or spore cases) are located on the edges of the underside of the pinnules (sub-leaflets).

The tripartite fronds of Eastern Bracken Fern are similar to those of the Oak Fern (Gymnocarpium dryopteris (L.) Newman), which also grows in the Adirondack Park. However, Oak Ferns prefer a shadier site than the Eastern Bracken Fern. Moreover, Oak Ferns are much smaller ferns, growing only about eight or nine inches tall.

Uses of Eastern Bracken Fern

There is conflicting evidence on the use of Eastern Bracken Fern as a food. Humans in many parts of the world have used the fiddleheads and rhizomes of the plant as food for centuries. In North America, some Native Americans peeled and steamed the young fiddleheads as a substitute for asparagus or canned them for winter use. The Bella Coola toasted and ate the rhizomes in summer. Other Native American groups roasted the rhizomes and pounded them into flour.

However, most sources stress the possible health risks posed by Bracken.. One authority suggests that the fiddleheads, while still in the uncurled stage, can be eaten raw or cooked in moderate quantities. Other sources caution against food use of the plant at any time, as even the fiddleheads have been found to contain carcinogenic substances.

Bracken was used extensively by native Americans as a medicinal plant, to treat a wide variety of ailments including nausea, stomach cramps, rheumatism, and headaches. For example, the Iroquois used a compound of the plant to treat rheumatism; it was also taken during the early stages of consumption. The Cherokee used the root as an antiseptic and tonic.

Bracken has many other human uses. It has been used in the past as thatch and livestock bedding. Until the mid-nineteenth century, Bracken ash was a source of potash for soap, bleach, and glassmaking. The leaves were used to make a brown dye; the rhizomes have been used to tan leather and dye wool. Bracken also has been put to a wide variety of household uses. Dried fronds have been used as a packing material for fruit, a lining for baskets, and a garden mulch. The roots were used by several native American groups in basketry. The fronds were used for bedding while camping, to line earth ovens, and as layers to dry food.

Wildlife Value of Eastern Bracken Fern

Bracken has some uses as a wildlife food. Although grazing mammals usually avoid it unless other food sources are scarce, White-tailed Deer have been known to graze occasionally on the foliage, mostly in spring, on the fiddleheads. Rabbits occasionally eat the fronds and rhizomes. The fern also hosts a variety of insect species. Insects which feed on Bracken include the caterpillars of several moths, including the Bracken Borer Moth, and the larvae of several species of sawflys and aphids.

Because of its height and density, Eastern Bracken Fern provides cover for deer, other mammals, and birds. Fronds of the Eastern Bracken Fern are used for nesting material or as a nest site by several birds which breed in the Adirondacks, including Palm Warblers, Indigo Buntings, White-throated Sparrows, and Golden-crowned Kinglets.

Distribution of Eastern Bracken Fern

Eastern Bracken Fern is said to be the most common of all the North American ferns. It is widespread throughout the northeast United States and the southern part of Canada.

In New York State, this fern has been documented in all counties, except Yates County in the western part of the state. Eastern Bracken Fern grows in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line.

Habitat of Eastern Bracken Fern

Eastern Bracken Fern is widespread and abundant throughout its range, thanks to its ability to thrive in a wide variety of soils and exposures. It does best in full sunlight, but can also grow in semi-shaded areas. It prefers well-drained soils, but can also be found on wetter sites. It seems to do best in thin, acidic soil.

Eastern Bracken Fern's flexibility in terms of soil and site requirements means that it can flourish in a wide variety of habitats. It occurs as a weed in pastures, old fields, thickets, and under power lines. It grows in hardwood or pine forests, roadsides, and woodland edges. Although this fern usually occurs in non-wetlands, it can occasionally be found in wetlands.

Like the Hay-scented Fern, the Eastern Bracken Fern is a pioneer plant, frequently gaining dominance after logging or fire. This fern reproduces by rhizomes, which are located deep in the ground and so can survive extremes of heat, cold, drought, and fire. Even if the fronds are destroyed by fire, some of the rhizomes survive, insulated by the soil, allowing the plant to emerge in the fire's aftermath. In fact, fire benefits the fern by removing its competition.

In the Adirondack Mountains, Eastern Bracken Fern can be found in a wide range of ecological communities, including:

- Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest

- Boreal Heath Barrens

- Limestone Woodland

- Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Pitch Pine-Heath Barrens

- Pitch Pine-Oak-Heath Rocky Summit

- Pitch Pine-Scrub Oak Barrens

- Red Pine Rocky Summit

- Sandstone Pavement Barrens

- Spruce Flats

- Successional Fern Meadow

- Successional Northern Sandplain Grassland

Eastern Bracken Ferns can be seen on many of the trails covered here, including the Old Orchard Loop at Heaven Hill and the sunny edges of the Logger's Loop Trail and the Barnum Brook Trail at the Paul Smith's College VIC. You can also find this fern identified with an interpretive sign in the Fern Garden adjacent to the Nature Museum at Heart Lake.

List of Adirondack Ferns

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 83.

Boughton Cobb. A Field Guide to Ferns and their Related Families. Northeastern and Central North America. Second Edition (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005), p. 203-205.

Michael Burgess. A Field Guide to the Ferns of New England and Adjacent New York, p. 116. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

Richard Mitchell. Atlas of New York State Ferns (New York State Museum, 1984), p. 8. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Eugene C. Ogden. Field Guide to Northeastern Ferns (New York State Museum, 1981), pp. 99, 102. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

William J. Cody and Donald M. Britton. Ferns and Fern Allies of Canada (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1989), p. 135-137. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

William J. Cody. Ferns of the Ottawa District (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1978), pp. 103-105. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

David B. Lellinger. A Field Manual of the Ferns & Fern Allies of the United States and Canada (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), pp. 211, Plate 260.

Anne C. Hallowell and Barbara G. Hallowell. Fern Finder. Second Edition (Nature Study Guild Publishers, 2001), pp. 32.

George Henry Tilton, "The Bracken Group," The Fern Lover's Companion. A Guide for the Northeastern States and Canada (Little, Brown, 1923. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

R.C. Benedict, "An Adirondack Fern List," American Fern Journal, Volume 6, Number 3, July-September 1916, pp. 81-85. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum (Desv.) Hultén. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Pteridium aquilinum. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

Flora of North America. Pteridium aquilinum (Linnaeus) Kuhn. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

NatureServe Explorer. Online Encyclopedia of Life. Bracken Fern. Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum - (Desv.) Underwood ex Heller. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Bracken Fern. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 95, 96, 100, 101-102, 102-103, 105-106, 108-109, 109, 118, 121-122. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Boreal Heath Barrens. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Limestone Woodland. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Heath Barrens. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Oak-Heath Rocky Summit. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Scrub Oak Barrens. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Red Pine Rocky Summit. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Sandstone Pavement Barrens. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 59. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Quick Guide to the Common Ferns of New England. Bracken. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum (Desv.) Underw. ex A.Heller. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Pteridium aquilinum. Bracken. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Bracken Fern. Pteridium aquilinum latiusculum. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden. Bracken Fern. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn var. latiusculum (Desv.) Underw. ex A. Heller. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Common Bracken. Pteridium aquilinum. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

Tom Kalinowski, "Natural History: The Ecology of Adirondack Fires," Adirondack Almanack, 26 March 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

Gary Wade et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380, p. 4. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169, p. 9. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

John Eastman. The Book of Field and Roadside: Open-Country Weeds, Trees, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Stackpole Books, 2003), pp. 60-65.

John Eastman, "Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea)," The Eastman Guide to Birds: Natural History Accounts for 150 North American Species. Kindle Edition. (Stackpole Books, 2012).

Plants for a Future. Pteridium aquilinum - (L.)Kuhn. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), pp. 403-404.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Revised and Updated. (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 162-163.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Medicinal Wild Plants. Revised and Updated. Second Edition, (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 32-33.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birds of North America. Subscription web site. Palm Warbler; Willow Flycatcher; Canada Warbler; Golden-crowned Kinglet; Indigo Bunting. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Iowa State University. BugGuide. Phytoliriomyza clara; Chirosia flavipennis; Olethreutes osmundana; Papaipema pterisii. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba. (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899). Retrieved 22 February 2017.

"What the Latin Name Means I," American Fern Journal, Volume 10, Number 4 (October-December 1920), pp. 113-115. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

J. B. Smith, "Bracken Lore," Tradition Today. Number 2. September 2012. Centre for English Traditional Heritage. Retrieved 14 January 2018.