Amphibians & Reptiles of the Adirondacks:

Pickerel Frog (Lithobates palustris)

The Pickerel Frog (Lithobates palustris) is a medium-sized frog with several parallel rows of square to rectangular spots on its back. It breeds in a wide variety of aquatic habitats near wooded areas in the Adirondack Mountains.

The Pickerel Frog is part of the order Anura. It is currently assigned to the Lithobates genus. Other frogs native to the Adirondack Mountains also assigned to this genus include American Bullfrog, Mink Frog, Northern Leopard Frog, Green Frog, and Wood Frog. The species name is derived from the Greek word "lith," meaning stone, and "bates," meaning one that walks or haunts The species name (palustris) is Latin for "of the marsh" – a reference to one of the Pickerel Frog's habitats during breeding season.

As the case for a number of other plant and animal species, the Pickerel Frog's taxonomic status is the subject of ongoing debate in the scientific community.

- At one time, the Pickerel Frog was assigned to the genus Rana. In 2006, as part of a larger revision, the Pickerel Frog (along with a number of other species) was removed from Rana and assigned to Lithobates, touching off a lively debate on whether the revision was justified and whether Lithobates should be recognized as a genus or as a subgenus within Rana.

- The debate remains unresolved. Some authorities (i.e. the Integrated Taxonomic Information System; Amphibian Species of the World, Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles) identify the species as Lithobates palustris. Others (i.e. AmphibiaWeb) continue to list the species as Rana palustris.

Two different explanations for the derivation of the nonscientific name – Pickerel Frog – have been suggested. One version holds that the species was named after the fish for which it is often used as bait. Another suggests that the name is based on a resemblance between the squarish or rectangular blotches on the Pickerel Frog's back and the rectangular markings characteristic of some species of Pickerel fish.

Pickerel Frog: Identification

The Pickerel Frog is a medium-sized frog, usually measuring 1¾ to three inches in length. Its background color is usually some shade of brown, often light brown, tan, or grayish. The skin is smooth.

Pickerel Frogs have long, unbroken dorsolateral foldsDorsolateral Folds: Ridges of raised skin running down the sides of a frog's back. Many members of the Ranidae family have such folds. down the side of its back.

- The folds, which are bronze or yellowish in color, extend to the groin area.

- Between the folds are several parallel rows of dark, squarish spots, often outlined in black. These spots may be merged into lengthwise stripes.

- There are one or two more rows of blotches along the sides of the Pickerel Frog's body. These markings are more irregular than those on the back.

The hind legs are long and muscular; they are patterned with dark cross bands. The toes on the hind legs are long and webbed. The forelimbs are marked with more irregular blotches. The front toes of Pickerel Frogs are not webbed. The inner thighs and groin area are bright yellow to orange.

The Pickerel Frog's head is broad, with a rounded or slightly pointed snout. Its eyes are large. The eardrums of both males and females are smaller than the eye. There is a light stripe extending along the jaw and a single dark blotch on the head.

Male and female Pickerel Frogs are similar in appearance, although female Pickerel Frogs are usually larger and darker in color than males. Males have swollen thumbs during the breeding season and internal vocal sacs located between the eardrum and the foreleg.

Similar Species: The Pickerel Frog is similar in appearance to the Northern Leopard Frog, which also occurs in the Adirondacks and also has dark spots. The Northern Leopard Frog's background color ranges from brown to bright green. Its spots are also dark, but they are round; each has a light border. By contrast, the Pickerel Frog's markings are square or rectangular and lack dark borders. In addition, the spots of the Northern Leopard Frog occur in a more random pattern than those of the Pickerel Frog. Northern Leopard Frogs are slightly larger than Pickerel Frogs.

Pickerel Frog: Behavior

Pickerel Frog Advertisement Call

As with the Green Frog, male Pickerel Frogs make several different vocalizations. Most common is the advertisement call given during breeding season. The Pickerel Frog's advertisement call is a steady, low-pitched croak lasting about two seconds. The call, which is significantly shorter than that of the Northern Leopard Frog, is usually described as sounding like a nasal snore. Other observers liken the Pickerel Frog's call to the mooing of a cow.

Male Pickerel Frogs call from clumps of emergent vegetation in shallows or from water near the shoreline. Males sometimes call while completely submerged. In the Adirondack region, Pickerel Frogs may be heard calling from early April to early July.

Pickerel Frogs have a long activity period. They emerge from their overwintering sites in March or April (depending on latitude and weather) and move to their breeding areas (pools or ponds). Throughout its range, the Pickerel Frog is most active from about mid-April to the beginning of May. At this time, they are said to be active day and night.

In late spring and early summer, Pickerel Frogs move away from their breeding areas, spending the summer away from water, often moving into grassy fields or nearby woodlands. They are most active when the humidity is high. During and after heavy summer rains, they are sometimes seen crossing or resting on roads in forested areas.

Pickerel Frogs are said to overwinter in muck at the bottom of ponds, springs, or other water bodies. Some sources suggest that they may also hibernate in terrestrial habitats.

Pickerel Frog: Diet

Like most frogs, adult Pickerel Frogs are carnivores. Pickerel Frogs are nonspecialists, and their diet depends largely on local availability. They consume beetles, caterpillars, ants, spiders, crickets, wasps, and lepidopteran larvae. Aquatic food items on the Pickerel Frog's menu include snails and small crayfish.

The tadpoles of Pickerel Frogs are largely herbivorous. They consume mostly algae and other plant material. They also scavenge dead animal matter in the muddy bottom.

Pickerel Frog: Reproduction

Pickerel Frogs breed in mid- to late spring in aquatic habitats, including woodland pools and ponds, floodplain wetlands, and marshes. Reproduction extends over a period of a month to six weeks. Female Pickerel Frogs lay their eggs in spherical masses in shallow water, attaching the eggs to dead or submerged vegetation at or near the water surface. The eggs are bicolored, with the upper surface dark brown and the lower surface yellow. Most masses contain 2,000 to 3,000 eggs. The eggs hatch in eleven to 21 days. Tadpoles metamorphize within two to three months.

Pickerel Frog: Distribution

Pickerel Frogs are widely distributed throughout the east, except the extreme southeast. This species is found in eastern North America from the Gaspé Peninsula west to Wisconsin, and south to southern South Carolina, northern Georgia, southern Mississippi and southeastern Texas.

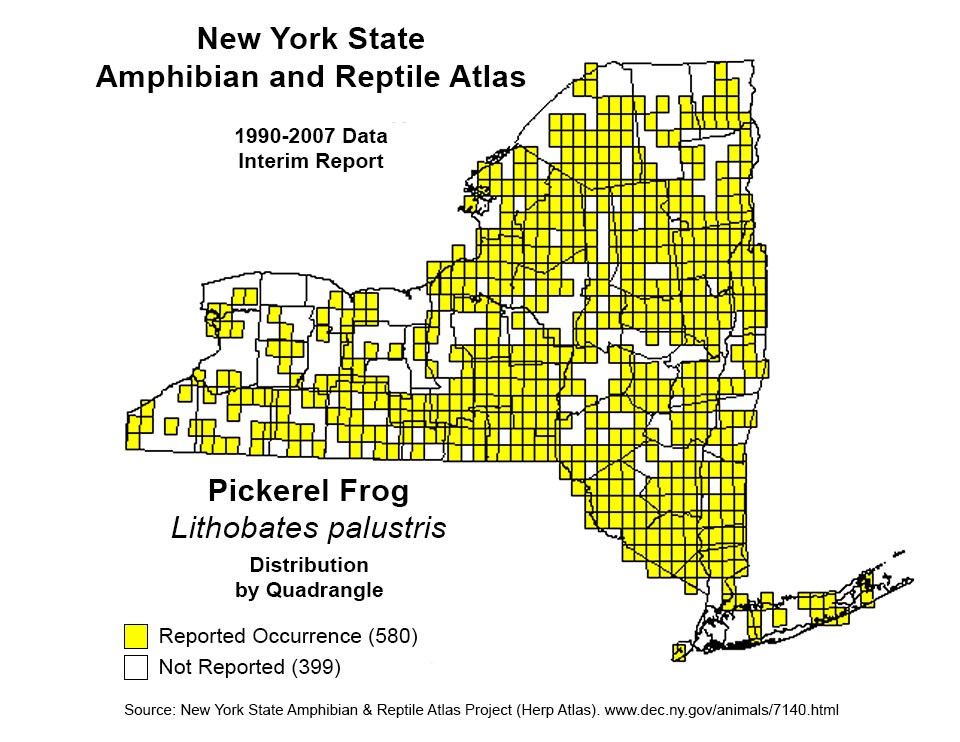

The Pickerel Frog is fairly widespread in New York State. The New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas shows the Pickerel Frog as present in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line. The pattern of iNaturalist observations within the Blue Line suggests that it is less commonly seen than the American Toad or Green Frog.

The Pickerel Frog is of low conservation concern. Its population is considered to be stable, although there have been some declines in Ontario, Canada.

Pickerel Frog tadpoles are vulnerable to predation by newts, diving beetles, and other aquatic predators. Potential predators of adult Pickerel Frogs include Green Frogs, American Bullfrogs, water snakes, and Common Garter Snakes. Some bird species (such as Bald Eagles) and mammals (such as Mink) may also prey on Pickerel Frogs. Pickerel Frogs, however, produce a poisonous skin secretion, which may protect them to some degree from predation.

Pickerel Frogs also may fall victim to vehicular traffic or human hunters. In New York State, the open season on Pickerel Frogs extends from 15 June through 30 September. There is no bag limit, although a license is required. The impact of human activities on the Pickerel Frog's habitats is unclear.

Pickerel Frog: Habitat

Pickerel Frogs are found in a wide variety of habitats. Their habitat varies with the season. During spring mating season, they are found in aquatic habitats, including marshes, bogs, fens, rocky ravines, meadow streams, and the weedy, shallow borders of ponds and lakes. After breeding, they disperse into the surrounding terrestrial habitat and may be found in deciduous or mixed woods and low-lying open fields and meadows.

Among the trails covered here, the most convenient place to seek Pickerel Frogs is at the Paul Smith's College VIC, along any of the trails that border Heron Marsh. During the spring breeding season, you are more likely to hear them than to see them, so listen for their low-pitched calls. Your best chance of seeing Pickerel Frogs is during the summer months, especially July and August, when they disperse to nearby terrestrial habitats.

List of Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles

References

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project. Species of Toads and Frogs Found in New York. Pickerel Frog Distribution Map. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Reptile and Amphibian Hunting Seasons. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Nature Explorer. Species Name. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Pickerel Frog. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Lithobates. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Pickerel Frog. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Frogs and Toads of New York. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wildlife Exposure Factors Handbook. Office of Research and Development. EPA/600/R-93/187 (December 1993). p. 2-445. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Rana palustris. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. SSAR North American Species Names Database. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Amphibian Species of the World 6.0. Lithobates Fitzinger,1843. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group 2015. Lithobates palustris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Virginia Herpetological Society. Pickerel Frog. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Bernard S. Martof, William M. Palmer, Joseph R. Railey, and Jack Dermid. Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas & Virginia. (University of North Carolina Press, 1980), p. 133. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Donald F. Mairs, "Pickerel Frog. Rana Palustris," in Malcolm L. Hunter Jr., John Albright, and Jane Arbuckle, Eds. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Maine. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station. Bulletin 838 (1992), pp. 74-76. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Pickerel Frog. Rana palustris. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), pp. 112-113, 156-157.

James P. Gibbs, Alvin R. Breisch, Peter K. Ducey, Glenn Johnson, John L. Behler, Richard C. Bothner. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New York State. Identification, Natural History, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. pp. 38-46. 110, 139-141, Plate 28.

James M. Ryan. Adirondack Wildlife. A Field Guide (University of New Hampshire Press, 2008), p. 104.

Arthur C. Hulse. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Cornell University Press, 2001), pp. 167-170. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

James H. Harding and David A Mifsud. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. Revised Edition (University of Michigan Press, 2017), pp. 164-168.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution (University Press of New England, 2001), pp. 45-46, 396-399, 423-426. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Lang Elliott, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. The Frogs and Toads of North America: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification, Behavior, and Calls(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009), p. 214-215. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John L. Behler and F. Wayne King. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), pp. 377, Plate 201.

Mary C. Dickerson. The Frog Book: North American Toads and Frogs, with a Study of the Habits and Life Histories of Those of the Northeastern States (Doubleday, Page and Company, 1906), pp. 188-192. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. American Bittern, American Crow, American Kestrel, Broad-winged Hawk, Common Merganser, Eastern Kingbird, Eastern Screech Owl, Hooded Merganser, Red-shouldered Hawk, Red-shouldered Hawk. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Pickerel Frog. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

Ontario Nature. Reptiles and Amphibians. Pickerel Frog. Lithobates palustris. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

Mac F. Given, "Vocalizations and Reproductive Behavior of Male Pickerel Frogs, Rana palustris," Journal of Herpetology, Volume 39, Number 2 (June, 2005), pp. 223-233. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Laurence M. Hardy and Larry R. Raymond, "Observations on the Activity of the Pickerel Frog, Rana palustris (Anura: Ranidae), in Northern Louisiana," Journal of Herpetology, Volume 25, Number 2 (June 1991), pp. 220-222. Retrieved 28 March 2020.