Wildlife of the Adirondacks:

Adirondack Butterflies and Moths

The Adirondack Park is home to 74 species of butterflies, as well as an unknown number of moth species. Resident butterflies include the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail, Painted Lady, the Monarch, and a host of fritillaries and sulphurs. Resident moths include the pale lime green Luna Moth, the prominently-patterned Cecropia Silkmoth, and the hummingbird-like Hummingbird Clearwing.

There are three main differences separating moths from butterflies: antennae, body size, and wing position when resting.

- Moths tend to have more robust and hairy bodies, feathery antennae, and rest with their wings spread out.

- Butterflies usually have narrower bodies, antennae that are wiry and end in a club, and rest with their wings folded.

- Another useful clue is to note what time of the day the insect is active. In general, moths are active at night and butterflies during the day.

Butterflies are divided into two superfamilies: the true butterflies (which have narrow bodies and brightly colored wings) and the skippers (which are stocky and have short, triangular wings).

List of Adirondack Butterflies and Moths

Identifying Adirondack Butterflies and Moths

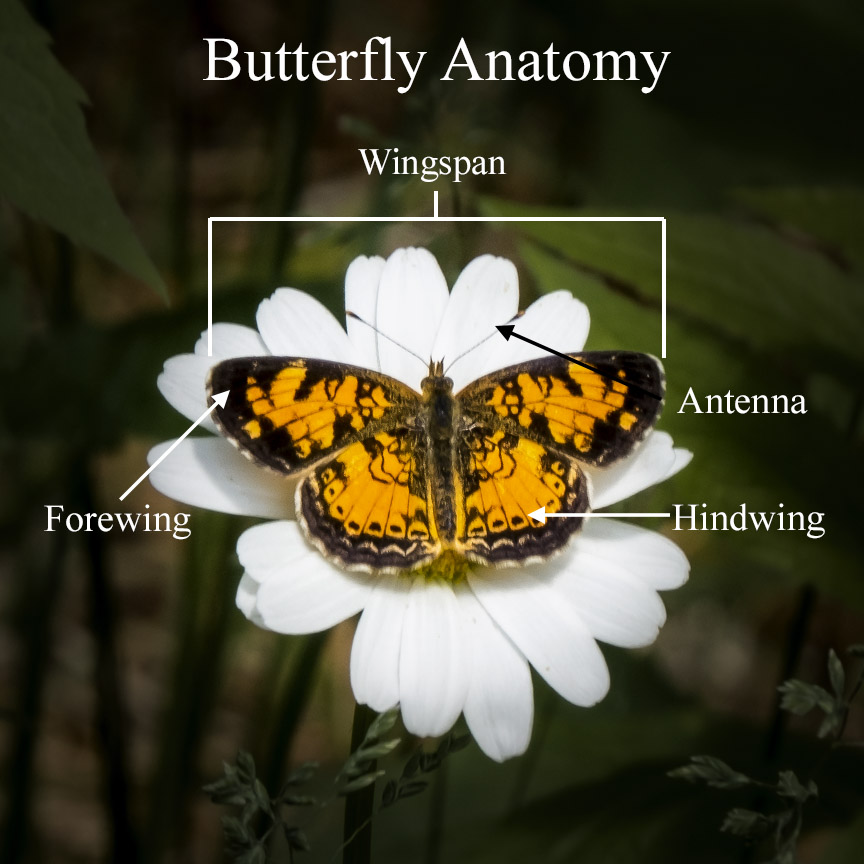

Clues to the identity of butterflies and moths include wingspan, color, pattern, and wing shape.

- Wingspan (the distance from forewing tip to forewing tip) is an important clue to identity. Small butterflies, like the Northern Crescent, have a wingspan of .75 inch to 1.75 inch. Medium butterflies, like the Painted Lady and American Lady, have a wingspan of 1.75 to 3.75 inches. Most of the butterflies in the Adirondack region are small to medium. Some of our resident moths, like the Cecropia Moth (a silkmoth), are much larger. The Cecropia's wingspan is four to six inches.

- The color and pattern of the wings provide other important clues. For butterflies, the forewings are larger and longer than the hindwings, which are generally more rounded. When the butterfly is viewed with open wings, from above, you are seeing the upperside of the wing. When the butterfly is resting with closed wings, you are seeing the underside of the wing. The color and pattern of these two views is often very different.

- Wing shape is another clue. Wing shape varies from triangular to nearly round, squarish, or long. On some butterflies, like the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail and Black Swallowtail, the hind wing has a distinctive tail.

The Life Cycle of Butterflies and Moths

Butterflies and moths undergo metamorphosis involving four distinct life states.

- Egg: Butterflies and moths start life as an egg, often laid on a leaf. Some butterflies have preferred host plants. An example is the Monarch, which often lays its eggs on milkweed leaves.

- Larva: The caterpillar (larva) which emerges from the egg spends its life eating the leaves or flowers of its host plants.

- Pupa: Because its skin cannot stretch as it grows, the caterpillar molts several times. The final molt produces the chrysalis (pupa). The color and shape of the chrysalis varies from species to species. As the adult butterfly begins to form inside the chrysalis, its wings and other features become visible.

- Adult: Eventually, the skin of the chrysalis splits, and the butterfly crawls out. Most butterflies have the ability to live off fat reserves left over from the constant munching they did as caterpillars. However, they also feed from tree sap and nectar in their adult state. Although their searches for flowers appear to be random, sensory clues play an important role. Butterflies can see ultraviolet light, which helps them identify a preferred plant. They can also determine the health of the plant by scratching it.

Butterflies live between 2 and 3 weeks, depending on species. The Spring Azure lives only two to four days, while the Mourning Cloak may live as long as ten to eleven months. The life span of Monarchs vary, from three weeks in the spring and summer to about ten months in the fall and winter. Large silkmoths live between 8 days and two weeks.

Butterflies have several strategies for coping with the harsh seasonal conditions that characterize the Adirondack region. Some butterflies hide in woodpiles, inside trees, or in houses. They enter a sleep-like condition called diapause that is probably triggered by decreasing day length. Some future butterflies overwinter as caterpillars hidden in a hibernaculum -- a leaf that is chewed and rolled into a winter nest and hangs from a twig with silk spun by the caterpillar. Slowed metabolism or arrested development in the case of eggs, caterpillars, or chrysalids allows butterflies to conserve their energy during the cold winter months.

Other butterflies migrate to escape the cold. Monarchs who live in the eastern US migrate south to Mexico, journeying 2500 miles; another generation returns. It is thought that the Painted Ladies migrate from warm southern areas or Mexico, while Red Admirals are thought to migrate from overwintering grounds in Florida and Texas

The butterfly's main predators are spiders, birds, frogs, snakes, rodents, bats, dragonflies, assassin bugs, and ambush bugs. In addition to defenses such as coloration and tailed wings, butterflies also have scales on their wings which seem to come off like powder. Scientists theorize that this adaptation is used to escape from spiders; butterflies shed their scales to release themselves from spider webs.

The bright colors of the butterfly serve as a vital aspect of the butterfly's defense. For instance, the bright orange wings of the Monarch Butterfly tell predators: "Don't eat me; I am toxic." Birds that have eaten a monarch vomit within fifteen seconds and do not fully recover for up to half an hour.

The swallow-like tails of some butterflies and the eye spots found on many butterfly wings also serve as a mechanism to ensure survival. These patterns and projections draw the predator's attention away from the most vital part of the butterfly's anatomy: its body.

Butterfly and Moth Habitats

Butterflies and can be found in a variety of habitats. Some butterflies can be found in cool, moist areas, such as woods. The Spotted Tussock Moth is usually found in boreal forests containing its host plants: deciduous trees. This small, attractive moth is usually seen in the Adirondack Mountains in June. One of our silkmoths, the Promethea Silkmoth, a large moth which may be seen in the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York in late May and early June, also favors deciduous woodlands. The Luna Moth, a large nocturnal moth that may be seen in the Adirondacks in June, also lives in deciduous hardwood forests. The Rosy Maple Moth can also be found in hardwood forests; its preferred host is the maple tree.

Other butterflies and moths favor wetlands. An example is the Silver-bordered Fritillary. This attractive orange and black butterfly prefers wet areas, such as swamps, marshes, and bogs. The Columbia Silkmoth, a large moth which may be seen in the Adirondack region from late May through June, is usually found near boggy, acidic areas. It breeds primarily on the tamarack, which is mainly confined to swamps and bogs.

Many butterflies prefer open fields with many flowers. Examples include the Common Buckeye, a medium-sized, brown butterfly with large eyespots, prefers open areas such as fields, meadows, and roadsides. The habitat of the Orange Sulphur includes nearly any open space, including open fields (particularly alfalfa fields), roadsides, and suburban areas. Common Ringlets, orange and brown butterflies that may be seen in the Adirondack Mountains early summer. also make their homes in grassy habitats, including fields, meadows, grasslands, roadsides, woodland edges and clearings.

Still other butterflies are generalists. The Aphrodite Fritillary, an orange butterfly with many black dots and lines, is an example. It was named after Aphrodite, the ancient Greek goddess of love, beauty, and fertility. Aphrodite Fritillaries have a wide tolerance of different habitats and may be found in wooded areas, open deciduous woods or coniferous woodlands, and prairie meadows. This species is fairly common across northern North America from the Rockies eastward.

Another generalist is the American Lady. This colorful butterfly is a fast-flying butterfly and often lights on flowers and other objects with its wings spread. It is found in a wide variety of habitats, including roadsides, sunny open spots, gardens, old fields, meadows, forest clearings, and stream beds. The Cabbage White is a small to medium-sized whitish butterfly, which is seen in the Adirondacks during much of the summer. This butterfly is said to be the most ubiquitous butterfly in the United States. The Cabbage White's habitat includes almost any type of open space, such as bogs, meadows, woods, roadsides, gardens, and suburbs.

Where to Find Butterflies and Moths in the Adirondacks

The most convenient place to view the butterflies and moths that make their home in the Adirondacks is Paul Smiths VIC Native Species Butterfly House and adjacent butterfly garden. The Butterfly House features butterflies and moths in all stages of development.

- The Butterfly House is usually open from mid-June to the end of August. Admission is free.

- Visitors can view native butterflies up close and learn about the life stages and migratory patterns of these colorful insects.

- Butterfly House volunteers are available to point out the species of butterflies in the house that day, provide information on the insect's life cycle, and identify specific plants that are favored by each species.

- There are nectar plants for food and host plants for egg-laying and caterpillar feeding, touch boxes, and information handouts.

There are a number of butterfly gardens in the Adirondack region. The Wild Center in Tupper Lake has a butterfly garden which is accessible from the Pond Loop Trail. Other butterfly gardens can be found at the the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake and the Adirondack Interpretive Center in Newcomb (part of SUNY ESF's Newcomb Campus).

References

Butterflies and Moths of North American. Species Profiles.

Government of Canada. Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. SpeciesBank.

Massachusetts Butterfly Club. Massachusetts Butterfly Species List.

ENature. Field Guides.

Ross A. Layberry, Peter W. Hall, and J. Donald Lafontaine. The Butterflies of Canada (University of Toronto Press, 1998).

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to Butterflies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981).

Jim P. Brock and Kenn Kaufman. Kaufman Field Guide to Butterflies of North America (Houghton Mifflin, 2003).

Paul A. Opler. A Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies (The Peterson Field Guide Series, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1992,1998).

Jeffrey Glassberg. Butterflies of North America (Michael Friedman Publishing, 2002).

James A. Scott. The Butterflies of North America. A Natural History and Field Guide (Stanford University Press, 1986).

Donald and Lillian Stokes. Stokes Butterfly Book. The Complete Guide to Butterfly Gardening, Identification, and Behavior (Little, Brown and Company, 1991).

Jeffrey Glassberg. Butterflies through Binoculars. The East. A Field Guide to the Butterflies of Eastern North America (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Paul A. Opler and George O. Krizek. Butterflies East of the Great Plains: An Illustrated Natural History (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984).

Rick Cech and Guy Tudor. Butterflies of the East Coast. An Observer's Guide (Princeton University Press, 2005).

Thomas J. Allen, Jim P. Brock, and Jeffrey Glassberg. Caterpillars in the Field and Garden. A Field Guide to the Butterfly Caterpillars of North America (Oxford University Press, 2005).