Trees of the Adirondacks:

Black Cherry (Prunus serotina)

The Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) is a deciduous tree that grows throughout New York State and the Adirondack Mountains. It is the largest and most important of the native cherries, reaching 125 feet in height in optimal conditions.

Black Cherry is a member of the Rose Family (Rosaceae).

- There is one other tree found in the Adirondacks in the genus Prunus: the Pin Cherry (Prunus pensylvanica), also called the Fire Cherry.

- The genus Prunus also includes a number of shrubs which grow in the Adirondack Park, including Choke Cherry (Prunus virginiana) and Canada Plum (Prunus nigra).

The common name – Black Cherry – is from the black color of the ripe fruits. The tree is also known as Wild Cherry, Wild Black Cherry, Mountain Black Cherry, and Rum Cherry. The latter name is a reference to a time when Appalachian pioneers flavored their rum or brandy with the fruit to make a drink called cherry bounce.

Identification of the Black Cherry

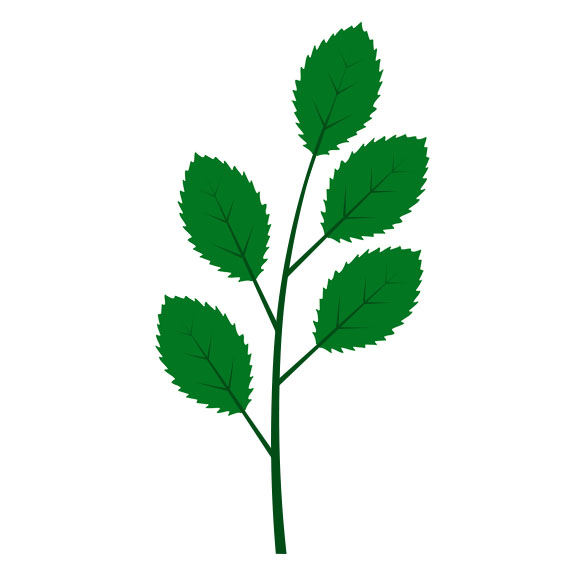

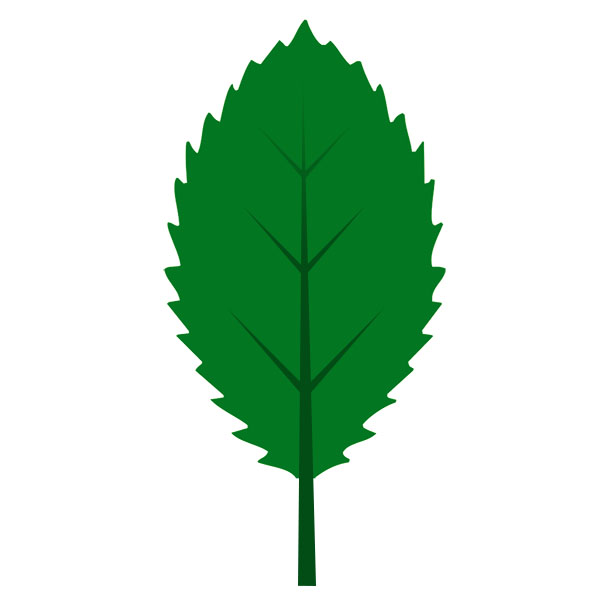

The leaves of the Black Cherry are oblong, with a long pointed tip and a tapering base. The leaves, like the branches, are alternate Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem.: they emerge from the stem one at a time. The edges of each leaf are finely toothed

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem.: they emerge from the stem one at a time. The edges of each leaf are finely toothed Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge.; the tiny teeth curve inward. In the spring, the leaves have a pair of brightly-colored stipules (outgrowths on either side of the leaf stalk).

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge.; the tiny teeth curve inward. In the spring, the leaves have a pair of brightly-colored stipules (outgrowths on either side of the leaf stalk).

Black Cherry leaves are shiny and dark green on the upper surface, light green below. The emerging leaves of the Black Cherry are often reddish. In fall, the leaves turn yellow to orange, then to red late in the season.

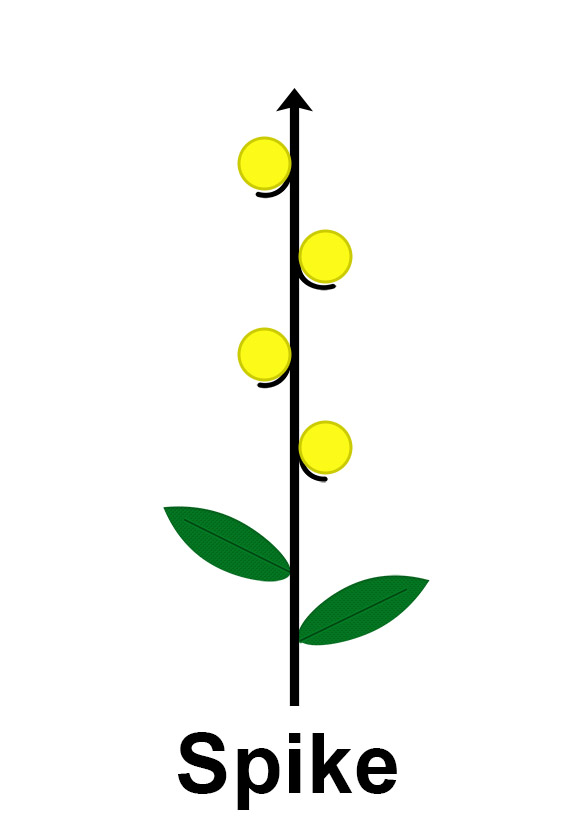

Black Cherries flower in late spring, after the leaves emerge. The insect-pollinated flowers are small (⅜") and white, arranged in terminal spikes Spike: An unbranched stalk of flowers. Each flower or flowerhead is attached directly to the central stalk. about five inches long. The edible fruit, which ripens in July and August in the Adirondack Mountains, occurs in dropping clusters. Each fruit is about ½" in diameter, with a single round seed. The green cherries turn dark red, then purple-black at maturity during the fall.

Spike: An unbranched stalk of flowers. Each flower or flowerhead is attached directly to the central stalk. about five inches long. The edible fruit, which ripens in July and August in the Adirondack Mountains, occurs in dropping clusters. Each fruit is about ½" in diameter, with a single round seed. The green cherries turn dark red, then purple-black at maturity during the fall.

Black Cherry bark is reddish-brown and smooth when young, with conspicuous, horizontal gray lines. The inner bark has a bitter almond smell. As the trees mature, the bark breaks into scales that are curled outward. If you break off one of the scales, you will find bright orange-brown underbark.

The bark of an older Black Cherry consists of layers of reddish-brown or black scales with upturned edges. The bark of a mature Black Cherry tree is said to resemble burnt corn flakes, providing a handy memory device: Black Cherry/Burnt Cornflakes.

Keys to identifying the Black Cherry and differentiating it from other deciduous trees include its leaves, bark, and growth habit.

- The oval leaves of the Black Cherry contrast sharply with the lobed leaves of Red Maple, Striped Maple, and Sugar Maple, but they are somewhat similar to those of the American Beech, Paper Birch, and Yellow Birch, in that the leaves of all four species are alternate and toothed. However, the leaves of birch trees are double toothed, meaning that the teeth are of different sizes, with small teeth along the contours of larger teeth. Both Black Cherry and American Beech leaves are single toothed and can be told apart by the fact that the leaves of the Black Cherry are finely toothed, while those of the American Beech are coarsely toothed.

- The scaly, dark bark of the mature Black Cherry is very different from that of the smooth, gray bark of the mature American Beech or the peeling bark of the Paper Birch and Yellow Birch.

- The crushed foliage and bark of Black Cherries have a distinctive cherry-like odor.

- The growth habit of the Black Cherry differentiates it from the Pin Cherry. Pin Cherries are smaller trees, rarely reaching 30 or 40 feet high. In addition, Pin Cherry leaves are longer and narrower than those of Black Cherry.

Uses of the Black Cherry

Black Cherry is the only cherry of commercial value in the US. Its hard, reddish wood is highly valued for furniture. It works well and takes polish well. The wood is also used for paneling, professional and scientific instruments, veneers, handles, interior trim, and toys.

The fruit is used for making jelly and wine and can also be used as a seasoning. However, any bitter fruit can be toxic and should not be eaten. Moreover, the twigs and leaves of the Black Cherry contain high levels of hydrocyanic or prussic acid; the foliage is toxic to both humans and livestock. The seeds as well contain high quantities of hydrogen cyanide and should not be eaten.

Black Cherry was used extensively by various native American groups to treat a wide variety of ailments, including coughs, colds, ulcers, fevers, measles, and burns. The Cherokee, for instance, reportedly created a decoction of inner bark which was used for laryngitis. The Chippewa applied a poultice of the inner bark to cuts and wounds. The Delaware are said to have made a cough syrup from the fruit.

Wildlife Value of the Black Cherry

Wild cherries, including the Black Cherry, are among the most important wildlife food plants. Red Foxes, Eastern Chipmunks, Eastern Cottontails, White-footed Mice, Gray Squirrels, and Red Squirrels forage on fallen cherries, while Black Bears and Raccoons climb Black Cherry trees for the fruits. During winter, voles feed on the bark at snow level.

Although the foliage of Black Cherry trees contains cyanide and may sicken or kill livestock that eat it, White-tailed Deer and Moose, which apparently are not sensitive to the toxins, browse on the twigs and foliage in the fall and winter. These animals spread the seeds to new areas.

Many insects use the Black Cherry as a source of food, particularly the leaves. The nectar and pollen of the flowers attract honeybees and bumblebees. Throughout its range, this species is said to be a primary food plant for more than 200 species of butterfly and moth caterpillars. The Black Cherry is a caterpillar host of many butterflies and moths, including Small-eyed Sphinx, New England Buckmoth, Canadian Tiger Swallowtail, Scalloped Sallow, and Dowdy Pinion.

Black Cherry fruits provide an important food source for numerous birds species.

- Some sources estimate that around seventy species of birds feed on Black Cherry fruits including American Robin, Brown Thrasher, Eastern Bluebird, Gray Catbird, Blue Jay, Willow Flycatcher, Wood Duck, Northern Flicker, Wood Thrush, Cedar Waxwing, and American Crow. Black cherries are also an important component of the summer and fall diets of Ruffed Grouse and Wild Turkey.

- Many songbirds feed on the fruits as they migrate south in the fall.

- Birds have been known to become intoxicated on slightly fermented cherries.

Black Cherries are part of the mixed woods forest that provides the breeding range for many bird species, including Hooded Warbler, Mourning Warbler, Wild Turkey, and Northern Saw-whet Owl.

Distribution of the Black Cherry

Black Cherry grows in eastern North America from western Minnesota south to eastern Texas, and eastward to the Atlantic from central Florida to Nova Scotia. In Canada, it is found in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and southern Quebec.

This species is found throughout New York State, including all counties within the Blue Line. Black Cherries are rather uncommon in the mountainous portions of the High Peaks region, but are more frequently seen in late successional forests at lower elevations.

Habitat of the Black Cherry

Black Cherries can grow under a wide range of climatic and soil conditions, growing on a variety of soil types, textures, and drainages.This species reportedly prefers mesic sites (places with a moderate amount of moisture). Throughout New York State, it can be found in hardwood forests, forest edges, and hedge rows.

In the Adirondack region, Black Cherry trees are typically seen in mixed forests on sites dominated by Sugar Maple and American Beech. Individual specimens can also be found in conifer forests. Black Cherry occurs in several ecological communities, including:

Black Cherry is generally considered to be a subclimax species – species which are more shade tolerant than the pioneer species but less shade tolerant than the climax species. Black Cherry, along with other species such as Red Maple, Balsam Fir, and Red Spruce, often follow pioneering Eastern White Pine, Fire Cherry, Paper Birch, and aspens.

- This pattern can be seen at the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area (FERDA) at Paul Smiths. Black Cherries were found on five of the seven blocks before logging, but they were not an abundant species on any of the blocks. Ten years after logging, Black Cherries were present in small numbers on all seven plots and had increased frequency on four of the blocks.

- Black Cherry also take advantage of openings created by weather events. A decade after the Great Blowdown of 1995, Black Cherry, along with Eastern White Pine and Yellow Birch, had begun to fill in the gaps created by the storm.

You can find Black Cherry along several of the interpretive trails on the Paul Smith's College VIC.

- Look for a very large Black Cherry tree on the west side of the Heron Marsh Trail, near signpost #14, between the board walk and the floating bridge.

- There are also a few Black Cherries on the Jenkins Mountain Trail, between the intersection with the Barnum Brook Trail and the intersection with the Heron Marsh Trail.

- There is also a Black Cherry tree on the Barnum Brook Trail, just after the fish barrier dam when walking the trail in a clockwise direction.

You can also find a Black Cherry with an interpretive sign on the ADK Tree Trail at Heart Lake.

Adirondack Tree List

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora. An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), pp. 75, 156.

Michael Kudish. Paul Smiths Flora II: Additional Vascular Plants; Bryophytes (Mosses and Liverworts); Soils and Vegetation; Local Forest History (Paul Smith's College, 1981), pp. 29-33, 38-41, 49, 99, 105.

E.H. Ketchledge. Forests and Trees of the Adirondacks High Peaks Region (Lake George, New York: Adirondack Mountain Club, 1996), pp. 126-129.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Prunus serotina var. serotina. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Black Cherry Prunus serotina Ehrh. var. serotina. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. Silvics of North America. Black Cherry. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Prunus serotina. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. NRCS National Plant Data Center & the Biota of North America Program. Plant Guide. Black Cherry. Prunus serotina Ehrh. var. serotina. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

Flora of North America. Prunus serotina Ehrhart var. serotina. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

Northern Forest Atlas. Black Cherry. Prunus Serotina. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Black Cherry. Prunus serotina Ehrh. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 102, 121, 122, 122-123. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Balsam Flats. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Boreal Heath Barrens. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Oak-Heath Rocky Summit. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 7. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Prunus serotina Ehrh. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

Gary Wade et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380, p. 5. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Trees of Wisconsin. Prunus serotina. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Online Encyclopedia of Life. Prunus serotina. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Prunus serotina Ehrh. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

Plants for a Future. Database. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), pp. 379.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birds of North America. The Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Hooded Warbler, Mourning Warbler, Wild Turkey, Northern Saw-whet Owl, Wood Duck, Northern Flicker, Wood Thrush, Cedar Waxwing, American Crow, Eastern Bluebird, Veery. Subscription web site. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

Butterflies and Moths of North America. Dowdy Pinion, Wild cherry sphinx, Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, White Admiral, Coral Hairstreak, Canadian Tiger Swallowtail. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

Ellen Rathbone, "Adirondack Tree Identification 102," The Adirondack Almanack, 18 November 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Michael Wojtech. Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast (University Press of New England, 2011), pp. 216-217.

William K. Chapman and Alan E. Bessette. Trees and Shrubs of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (Utica, New York: North Country Books, Inc., 1990), p. 45, Plate 14.

Stan Tekiela. Trees of New York. Field Guide. (Cambridge, Minnesota: Adventure Publications, Inc., 2006), pp. 96-97.

Peter J. Marchand. Nature Guide to the Northern Forest. Exploring the Ecology of the Forests of New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine (Boston, Massachusetts: Appalachian Mountain Club Books, 2010), p. 81.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Eastern Trees (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), pp. 104-105, 323-324.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958,1972), pp. 13, 236, 340.

Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, and Richard Spellenberg. Trees of Eastern North America (Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 546-547.

C. Frank Brockman. Trees of North America (New York: St. Martin's Press), pp. 166-167.

Keith Rushforth and Charles Hollis. Field Guide to the Trees of North America (Washington, D.C., National Geographic, 2006), p.171.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Trees (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980, 1995), Plates 136, 447, 548; pp. 506-507.

Allen J. Coombes. Trees (New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc., 1992), p. 269.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife and Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (New York: Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 329-331. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

Bruce Kershner, et al. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Trees of North America (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2008), p.335 .

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket. Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1992), pp. 52-55.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Trees (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), pp. 264-265.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba. (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899). p. 87. Retrieved 22 February 2017.