Birds of the Adirondacks:

Canada Jay (Perisoreus canadensis)

The Canada Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) is a fluffy, gray and white bird with a small bill and dark markings on the head. It is a permanent resident of coniferous forests in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. The Canada Jay is a member of the Corvidae family, which includes crows and other jays (such as the Blue Jay).

The Canada Jay has undergone a recent name change.

- Until the mid-20th century, the bird was referred to as the Canada Jay. In 1957, the American Ornithologists' Union changed the name to Gray Jay, adopting the American spelling of "gray" (vice the Canadian spelling "grey").

- Efforts to change the bird's name back to its original were prompted by a series of efforts among Canadian birders to get the Gray Jay recognized as Canada's national bird. These efforts, spearheaded by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, motivated Dan Strickland, a retired Algonquin Provincial Park naturalist, to explore why the name "Canada Jay" had been dropped. Strickland's research convinced him that there had been no logical reason for the name change, and he wrote a formal proposal to the American Ornithological Society (AOS), which produces a standardized checklist of English names of American birds, asking it to restore the name "Canada Jay".

- The AOS supported the proposal, and the new name was added to the AOS checklist in July 2018.

- Efforts to have the newly renamed Canada Jay adopted officially as Canada's national bird are ongoing.

Unofficial names for the Canada Jay include the Labrador Jay, Alaska Jay, Idaho Jay, Oregon Jay, Rocky Mountain Jay, Alberta Jay, White-headed Jay, Whiskey Jack, and Whiskey John.

- The Canada Jay is often informally referred to as Camp Robber, reflecting the bird's propensity to visit campsites demanding a meal.

- The Canada Jay has also been called the Carrion Bird or Meat Bird, which is a reference to the fact that the bird's diet sometimes includes carrion.

Canada Jay: Identification

Canada Jays are stocky gray and white birds, slightly smaller than a Blue Jay, with fluffy plumage that it puffs up in cold weather. Adult Canada Jays are about 11.5 inches long, with a wing span of about 18 inches. Males and females are nearly identical.

There is fairly extensive geographic variation in the Canada Jay's appearance. The subspecies which is found in the Adirondack Park is Perisoreus canadensis canadensis, referred to in guidebooks variously as Adult Taiga, Adult Northern, or Boreal Adult.

- Our version of the Canada Jay has a white forehead with a dusky black nape.

- The neck, throat, and upper breast are white, while the lower breast and belly are ashy gray.

- The Canada Jay has a very short bill and dark slate to black legs and toes.

- The iris is dark grayish-brown to brown.

- The Canada Jay's head is round, lacking the crest seen on the more familiar Blue Jay.

Canada Jays along the Pacific coast have extensive dark on their heads and a whiter belly. Canada Jays that live in the Rocky Mountains are much paler than our birds, with a mostly white head and paler gray on their backs.

Some observers have described the adult Canada Jay as a bird which looks like an overgrown chickadee.

Juvenile Canada Jays are sooty gray to black in all parts of the bird's range. They have a dark slate gray head and upperparts, with faint white whiskers. They are slightly paler gray below.

Canada Jays retain their juvenile plumage from April to August/September. Juvenile Canada Jays molt in early fall, after which they resemble adults.

Canada Jay: Sounds

Canada Jays have a broad array of vocalizations. Their "whisper song" is a series of light, melodious notes, interspersed with clicking sounds.

Canada Jays also communicate with a wide array of whistles, screams, and contact notes. They use a series of soft, musical notes as alarm whistles to signal the presence of an aerial predator. Canada Jays in a social group keep in contact with a single, frequently repeated note. Birders who venture into the territory of a Canada Jay's territory are often greeted with loud, harsh chatter, just before the birds swoop into view to demand food.

Like Blue Jays, Canada Jays can imitate a number of different calls, particularly of predators such as Red-tailed Hawks, Broad-winged Hawks, and Merlins. The purpose of this mimicking is not clear, but could be designed to signal the presence of a threat to other group members or to confuse the predator itself.

Canada Jay: Behavior

Canada Jays are usually seen traveling in family groups of two to four birds. They are tame, bold, and curious, often flying up to check out strangers in their territory. They become quickly habituated to food sources and are attracted to campsites and cabins, where their habit of stealing food has led hikers to refer to them as "camp robbers." Canada Jays are frequently seen on the Bloomingdale Bog Trail surrounding walkers with loud demands for food, then swooping down to land on a birder's hands to grab a raisin or piece of granola.

Canada Jay: Migration

Canada Jays are essentially non-migratory. They are permanent, year-round residents in the Adirondack Park.

Canada Jay: Diet and Foraging

Canada Jays are omnivorous, with a remarkably varied diet. Their plant food includes berries, seeds, and fungi. Animal food includes bees, caterpillars, grasshoppers, wasps, and other insects. They also attack rodents and small birds.

Canada Jays are nest predators, preying on the eggs and nestlings of many bird species including White-throated Sparrows, Ruby-crowned Kinglets, Lincoln's Sparrows, and Magnolia Warblers. Another item on their menu is carrion, especially in winter, when they scavenge kills left by other predators.

Canada Jays store their food for consumption during the winter, a strategy which allows them to survive and nest through the harsh winters in boreal forests. They use a sticky saliva to coat individual chunks of food, then deposit the chunk in trees behind bark, under lichen, or in tree forks.

Canada Jay: Breeding and Family Life

Canada Jays are reportedly monogamous. The pair members are rarely apart and will usually remain together for life, unless one of the partners disappears. The breeding pair occupies and defends a permanent territory, maintaining it by chasing out intruders. Canada Jay pairs are often seen outside the breeding season accompanied by one or two nonbreeding birds.

In contrast to most other birds that make their homes in the Adirondacks and other boreal forests, Canada Jays nest in late winter rather than spring, with nest building as early as February. The reason for this early nesting is not known, although several hypotheses have been advanced.

- Early breeding gives the young longer to develop survival skills before the onset of the next winter.

- Early breeding helps subordinate juveniles (who are kicked out of the natal territory) to compete for spaces available for nonbreeders.

- Early breeding permits adults to devote more time to food storage after their young have been reared.

Canada Jays build their nests in trees (typically Black Spruce, Balsam Fir, or White Spruce), usually choosing a location close to the tree trunk, at low or moderate height. The male generally chooses the site and initially does most of the nest-building work. The nest consists of twigs, bark, and lichen, lined with moss and feathers.

Egg laying begins three or four weeks after the nest is complete, usually in March or April, resulting in three to four pale gray to greenish eggs. Only the female incubates the eggs, which hatch about 18 or 19 days later. Both parents feed the nestlings.

Young Canada Jays leave the nest about 22-24 days after hatching and remain with their parents for at least another month. The family beings to travel together as a group when the young jays are 42 to 45 days old. Soon thereafter, the dominant juvenile expels his subordinate siblings, who sometimes attach themselves to unrelated pairs.

Distribution of the Canada Jay

Canada Jays are found from Alaska east across Canada to Labrador. Their range extends south to the western edge of Washington and California, the mountains of Arizona, along the Rocky Mountains, New Mexico, northern Minnesota and Wisconsin, northern New York State, and northern New England.

A majority of Canada Jays (an estimated 73%) reside in Canada's boreal forest. Some evidence suggests that Gray Jay populations at the southern edge of their range in Canada are declining, possibly in response to climate change.

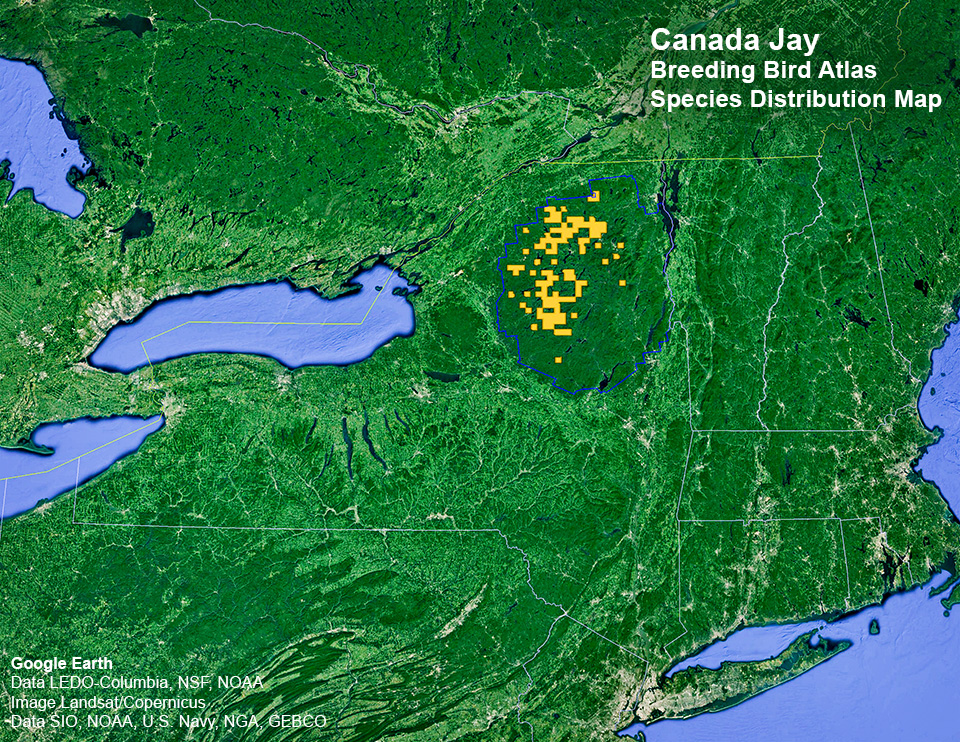

Within New York State, the Canada Jay is found only within the Adirondack Park. Canada Jays are concentrated in the central Adirondacks and western Adirondack foothills.

Canada Jay: Habitat

Canada Jays reside in conifer and mixed conifer-deciduous forests where spruce trees are present. Their habitats include Black Spruce bogs in eastern Canada, Sitka Spruce and Douglas-fir forests on the northwest coast, and aspen and Engelmann Spruce forests in the Rockies.

In the Adirondack Park, Canada Jays prefer medium to mature boreal forest. Ecological communities in New York State that host Canada Jays include:

Where to find Canada Jays in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Canada Jays

- High Peaks Region

- The High Peaks

- Chubb River Swamp

- Northern Region

- Whitney Wilderness

- Bog River and Lows Lake

- Five Ponds Wilderness

- Massawepie Mire

- Madawaska

- Jones and Osgood Ponds

- Bloomingdale Bog

- Bigelow Road

- California Road and Debar Pond

- West-Central Region

- Moose River Plains

- Cedar River Flow

- Third Lake Creek

- South Inlet

- Raquette Lake Inlets

- Shallow Lake

- Ferd's Bog

- Wheeler Pond Loop

- Tug Hill Wildlife Management Area

Species accounts for the Canada Jay from the 1980-85 and 2000-05 Breeding Bird Surveys indicate that Canada Jays within New York State are restricted to the Adirondack Mountains. Canada Jays are most commonly found in Black Spruce forests at lower elevations. Canada Jays also occur in areas with White Spruce and Red Spruce on higher ground.

It is thought that the replacement of spruce trees by Red Pine, Scotch Pine, and Norway Spruce after logging or fires may have made parts of the Adirondacks unsuitable to the Canada Jay.

The two Breeding Bird Surveys show that, within the Adirondacks, Canada Jays are most common in the central and northern Adirondacks and the western Adirondack foothills. Canada Jays are less common in the High Peaks region and appear to be largely absent from the eastern Adirondack foothills and Clinton County, where historical data suggests that they were a fairly common resident in the early 20th century.

Data from eBird listings are generally consistent with the data from the Breeding Bird Surveys. Within New York State, Canada Jay sightings are largely restricted to the Adirondack region, with most of the sightings in the central and western Adirondacks (near Tupper Lake, Long Lake, and Newcomb), and a cluster of multiple sightings along the Bloomingdale Bog Trail in Franklin County. There are fewer Canada Jay sightings in the High Peaks area, and none in Clinton County or in the eastern Adirondack foothills.

The sighting pattern for the Canada Jay from iNaturalist is similar. Most sightings are clustered in popular birding locations often recommended to birders looking for the Canada Jay, particularly the Bloomingdale Bog Trail.

Adirondack birders in search of Canada Jays have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the northern Adirondacks and west-central region, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide.

- Among the trails covered here, the Bloomingdale Bog Trail is probably the most reliable place to see Canada Jays. The most convenient access for those seeking Canada Jays is the north entrance to the trail, on the Bloomingdale-Gabriels road. Canada Jays are easily found by walking southwest along the trail for about five or ten minutes. The Canada Jays along this part of the trail have been accustomed to demanding food from bird watchers and will usually swoop in for treats.

- Canada Jays have also been seen on the Boreal Life Trail at the Paul Smith's College VIC, although less frequently than along the Bloomingdale Bog Trail.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Gray Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. Canada Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Canada Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Canada Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. Canada Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Species Map. Canada Jay. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Gray Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Canada Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Gray Jay. Perisoreus canadensis. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. Breeding Bird Atlas: Breeding Bird Atlas dataset for Google Maps and Google Earth. Species Distributions Map. Gray Jay. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 378-379, 638.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 26.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), pp. 82-83.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), p. 166.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 62-65, 78-80, 92-101, 105-107, 123-133, 136-146, 150-162, 166-168, 183-185, 209-211.

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Verne E. Davison. Attracting Birds from the Prairies to the Atlantic (Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1967), p. 88.

Margaret McKenny. Birds in the Garden and How to Attract Them (Grosset & Dunlap, 1939), pp. 68-69.

David Allen Sibley. Sibley Birds East. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 282.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), p. 381.

Michel Vanner. A Field Guide to the Birds of North America (Paragon Publishing, 2006), p. 166.

Roger Tory Peterson. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Sixth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), pp. 232-233.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Eastern Region (Little, Brown and Company, 2013), p. 302.

Jonathan Alderfer, Ed. Complete Birds of North America. Second Edition (National Geographic, 2014), p. 470.

Richard Crossley. The Crossley ID Guide (Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 308.

American Museum of Natural History. Birds of North America. Revised Edition (Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2016), p. 458.

John Bull and John Farrand, Jr. Eds. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. Eastern Region. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p. 602, 603, Plate 605.

Edward S. Brinkley. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), p. 413.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 76, 123. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Balsam Flats. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Mountain Spruce-Fir Forest. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

The Nature Conservancy. Acadian-Appalachian Montane Spruce-Fir-Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

The Nature Conservancy. Acadian Low Elevation Spruce-Fir-Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Canada Jay. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

iNaturalist. Adirondack All-Taxa Biodiversity Inventory. Canada Jay. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

Jacques Ibarzabal and André Desrochers, "A Nest Predator's View of a Managed Forest: Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) Movement Patterns in Response to Forest Edges," The Auk, Volume 121, Number 1 (January 2004), pp. 162-169. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

Dan Strickland, "How the Canada Jay lost its name and why it matters," Ontario Birds, Volume 35, Issue 1, 2017, pp. 2-16.

Abi Hayward, "How the Canada jay got its name back," Canadian Geographic, 30 May 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

Arthur Cleveland Bent. Life Histories of North American Jays, Crows, and Titmice: Order Passeriformes. (Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 191, 1946), pp. 1-13. Retrieved 24 August 2020.