Wildflowers of the Adirondacks:

Roundleaf Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia)

Roundleaf Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) is tiny insectivorous wildflower which grows in acidic wetlands in the Adirondack Mountains and throughout New York State. It is a member of the Sundew (Droseraceae) family.

The term "droseros" is Greek for "dewy" and refers to the moist, glistening drops on the leaves, to which small organisms stick. The term "rodundifolia" comes from the Latin, meaning "round leaves." Other common names for the plant include Common Sundew, Round-leaved Sundew, and Round-leaf Sundew.

The Roundleaf Sundew is among a specialized group of bog plants that trap insects.

- The high acidity which characterizes the bog environment discourages the growth of fungi and bacteria, retarding decomposition and creating a chronic shortage of the mineral nutrients, such as nitrogen, that plants need for growth and reproduction.

- Insectivorous plants such as sundews, bladderworts, and the Pitcher Plant, consume insects as a supplemental source of nitrogen. This allows such plants to survive on nutrient-poor soils. The increased consumption of nitrogen from insect prey benefits plant growth, flowering, and seed production.

The extent to which Roundleaf Sundew depends on its insect prey for nutrition depends on the site. Studies have shown that the proportion of nitrogen derived from carnivory varies from about a quarter to about half. Reliance on carnivory is highest in nutrient-poor, open habitats. On shadier sites, under more nutrient-rich conditions, the Roundleaf Sundew reduces its investment in carnivory.

Identification of Roundleaf Sundew

The Roundleaf Sundew is a small plant, growing from two to ten inches high. The root system is usually shallow and consists of a taproot.

The rosette of basalBasal: Leaves are confined to the base of the stem. leaves provides the primary key to identification.

- The leaves are small and round (about ¾ inch across).

- The upper surfaces are covered with reddish, glandular hairs, each tipped with a clear, sticky secretion that glistens in the sun.

- The green or red leaf stalks are flat, ½ to 2 inches long, and covered with fine hairs.

- The leaves generally lie flat or nearly flat against the ground.

A similar species Spatulate-leaved Sundew (Drosera intermedia) also grows in our area, but it has spoon-shaped flowers, and its leaf stalks lack hairs.

Roundleaf Sundew's leaves are adapted to catch and consume insect prey.

- Insects are trapped by the sticky droplets at the tip of the longer, outer tentacles. The plant responds by folding the tentacles around the prey. Plant response depends on what is being devoured, with more rapid response when the victim is actively struggling.

- The prey is digested when the shorter hairs on the inner surface of the leaf secrete a mucilage containing digestive enzymes and an anesthetic that debilitates the prey.

- The captured insect becomes digested into soluble materials that are absorbed into the leaf cells and later distributed to other parts of the plant.

- Midges and other small flies reportedly constitute Roundleaf Sundew's main prey.

The role of the distinctive red color of the leaves is unclear. One hypothesis is that it is designed to attract insects. However, this theory has not been supported by experiments.

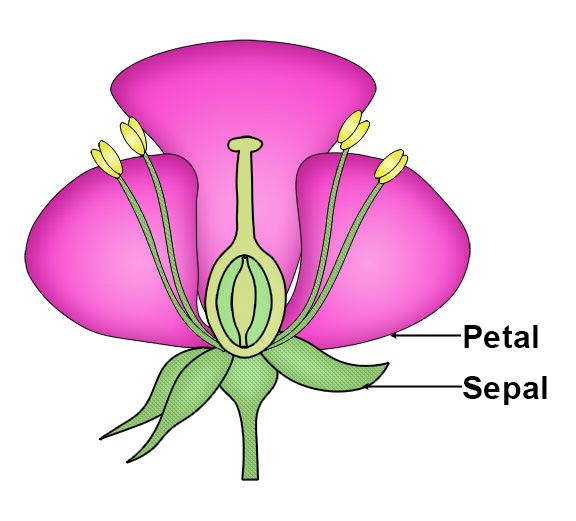

The flower of the Roundleaf Sundew is small and white (sometimes pinkish), occurring at the end of a long, leafless stem rising above the leaf rosette. The flowers are about ¼ inch wide, with five petals Petals: Modified leaves that surround the reproductive parts of flowers. Petals are often brightly colored or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. and five tiny sepals

Petals: Modified leaves that surround the reproductive parts of flowers. Petals are often brightly colored or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. and five tiny sepals.gif) Sepals: The parts that look like little green leaves and cover the outside of a flower bud to protect the flower before it opens.. The flowers grow in one-sided clusters. The flowering stem is tightly curled and unfurls as the flowers bloom.

Sepals: The parts that look like little green leaves and cover the outside of a flower bud to protect the flower before it opens.. The flowers grow in one-sided clusters. The flowering stem is tightly curled and unfurls as the flowers bloom.

In the Adirondack region, Roundleaf Sundews usually bloom in July or early August. A tally of flowering dates for the upland Adirondack areas compiled by Michael Kudish, based on data collected from the early seventies to the early nineties, lists the bud date as 17 July and the flower date as 4 August.

The fruit of Roundleaf Sundew consists of capsules with many small, light brown seeds. Seeds may be distributed by flowing water, wind, the feet or feathers of birds, or mammals' fur.

Uses of Roundleaf Sundew

Roundleaf Sundew appears to have limited edible or medicinal use in the US. Native American groups reportedly made little use of this plant.

Historical accounts suggest that Roundleaf Sundew has been used in the past in Europe as a herbal remedy for a variety of ailments, including warts, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and whooping cough. For instance, a tincture of the plant was said to be used for dry, spasmodic coughs; a poultice of plant juice was reportedly used on corns and warts. Harvesting of the plant for use in European herbal medicine has raised conservation concerns.

Wildlife Value of Roundleaf Sundew

Roundleaf Sundew has minimal food or cover value in our area, although the wetland habitats that host them are important breeding areas for boreal birds, such as the Palm Warbler and Lincoln's Sparrow. The plant may be an important food source for bog-dwelling ants, who reportedly scavenge up to two-thirds of the prey caught by the plant.

Distribution of Roundleaf Sundew

Roundleaf Sundew is generally circumboreal, found in all of northern Europe and much of Siberia. In North America, it grows in the eastern half of the United States and throughout Canada.

- Roundleaf Sundew occurs south along the Pacific coast to California and inland as far as western Montana and western Colorado.

- In the East, round-leaved sundew is found from Nova Scotia south to Georgia, Florida, and Alabama and west to the Mississippi River, Iowa, and Minnesota.

- This plant is listed as Endangered in Illinois and Iowa, Threatened in Tennessee, and Exploitably Vulnerable in New York.

In New York State, Roundleaf Sundew may be found in most counties in the northeastern part of the state. It is found in all Adirondack Park Blue Line counties except Clinton and Warren counties.

Habitat of Roundleaf Sundew

Roundleaf Sundew is classified as an obligate wetland (OBL) species, meaning that it is generally restricted to sites that provide continually moist or wet situations. Roundleaf Sundew is most often found in acidic bogs, but can also be seen growing in swamps or on rotting logs, mossy crevices, and floating sphagnum mats or hummocks. This species is also found on pond, lake, and stream margins. Roundleaf Sundew prefers full sun, but can survive in limited shade.

In the Adirondack Mountains, Roundleaf Sundew is found in several ecological communities, including:

In inland poor fens, for instance, look for Roundleaf Sundew growing on sphagnum. Characteristic shrubs in this ecological community include Bog Laurel, Sheep Laurel, Leatherleaf, Bog Rosemary, and Labrador Tea. There may be scattered stunted trees, such as Tamarack and Black Spruce. Characteristic herbs growing near Roundleaf Sundew include Rose Pogonia, Grass Pink, and Pitcher Plant.

A convenient place in our area to find Roundleaf Sundew is on Barnum Bog at the Paul Smiths VIC, where it may be viewed from the boardwalk on the Boreal Life Trail. Look for Roundleaf Sundew growing on the decaying trunks of trees along the shores of area ponds and in the peat moss of alpine bogs at high elevations.

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 54-55, 132, 242.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Round-leaved Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia L. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Roundleaf Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia L. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Drosera rotundifolia. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Wolf, E., E. Gage, and D.J. Cooper. Drosera rotundifolia L. (roundleaf sundew): A Technical Conservation Assessment. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. 29 June 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Flora of North America. Drosera rotundifolia Linnaeus. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

NatureServe Explorer. Online Encyclopedia of Life. Roundleaf Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia – L. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Round-leaved Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia L. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Alpine Sliding Fen. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Dwarf Shrub Bog. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Inland Poor Fen. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Medium Fen. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Graminoid Fen. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Sloping Fen. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Riverside Ice Meadow. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 21. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Drosera rotundifolia L. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Round-leaved Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Roundleaf sundew. Drosera rotundifolia. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Online Encyclopedia of Life. Round-leaved Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Round-leaved Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

Anne McGrath. Wildflowers of the Adirondacks (EarthWords, 2000), p. 16.

Roger Tory Peterson and Margaret McKenny. A Field Guide to Wildflowers. Northeastern and North-central North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1968), pp. 20-21, 232-233.

Doug Ladd. North Woods Wildflowers (Falcon Publishing, 2001), p. 181.

Lawrence Newcomb. Newcomb's Wildflower Guide (Little Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 174-175.

Charles W. Johnson. Bogs of the Northeast (University Press of New England, 1985), pp. 29, 71, 83, 117-120.

Meiyin Wu & Dennis Kalma. Wetland Plants of the Adirondacks: Herbaceous Plants and Aquatic Plants (Trafford Publishing, 2011), p. 48.

Ronald B. Davis. Bogs & Fens. A Guide to the Peatland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 220-221.

Ronald B. Davis. Bogs & Fens. A Guide to the Peatland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 220-221.

Donald D. Cox. A Naturalist's Guide to Wetland Plants. An Ecology for Eastern North America (Syracuse University Press, 2002), pp. 16, 87-88.

David M. Brandenburg. Field Guide to Wildflowers of North America (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2010), p. 215.

John Kricher. A Field Guide to Eastern Forests. North America (Houghton Mifflin, 1998), pp. 68-69, 257-258.

Timothy Coffey. The History and Folklore of North American Wildflowers (FactsOnFile, 1993), pp. 71-71.

Wilbur H. Duncan and Marion B. Duncan. Wildflowers of the Eastern United States (The University of Georgia Press, 1999), p. 22.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Wildflowers. Eastern Region (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), pp. 504-505, Plate 74.

William K. Chapman et al., Wildflowers of New York in Color (Syracuse University Press, 1998), p. 8.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 183-186.

Plants for a Future. Drosera rotundifolia - L. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), pp. 32-33.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Roundleaf Sundew. Drosera rotundifolia L. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Nancy G. Slack and Allison W. Bell. Adirondack Alpine Summits: An Ecological Field Guide (Adirondack Mountain Club, Inc., 2006), p. 56.

Allen J. Coombes. Dictionary of Plant Names (Timber Press, 1994), p. 62.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba. (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899)p. 96. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Cairn C. Krafft and Steven N. Handel. “The Role of Carnivory in the Growth and Reproduction of Drosera filiformis and D. rotundifolia,” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, Vol. 118, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1991), pp. 12-19. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

G. Foot, S. P. Rice, and J. Millett, “Red trap colour of the carnivorous plant Drosera rotundifolia does not serve a prey attraction or camouflage function,” Biology Letters, Volume 10, Issue 4, April 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

L. Magnus Thorén. et. Al., “Resource availability affects investment in carnivory in Drosera rotundifolia,” New Phytologist, August 2003, Volume 159, Issue 2, pp. 507-511. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

J. Millett, et.al., “Reliance on prey-derived nitrogen by the carnivorous plant Drosera rotundifolia decreases with increasing nitrogen deposition,” New Phytologist, Volume 195, Issue 1, July 2012, pp. 182-188. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

Aaron M. Ellison, “They Really Do Eat Insects,” C.J. Boulter, et al., Darwin-Inspired Learning (Sense Publishers, 2014), pp. 243-256. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

Charles Darwin. Insectivorous Plants (D. Appleton and Company, 1897). Retrieved 16 November 2017.

Wildflowers of the Adirondack Park