Birds of the Adirondacks:

Nashville Warbler (Leiothlypis ruficapilla)

Nashville Warblers (Leiothlypis ruficapilla) have a gray head, white eye ring, and yellow throat, breast, and belly. They spend summer in the Adirondacks, breeding in second-growth forests and wetland areas.

The Nashville Warbler is a member of the New World Warbler or Wood Warbler family (Parulidae). New World Warblers are small, insect-eating songbirds which winter in warmer areas to the south and migrate north each spring to breed.

As with many other birds, the Nashville Warbler has been recategorized several times, resulting in multiple changes in its scientific name.

- In the 1886 edition of the American Ornithologists' Union listing, the Nashville Warbler was listed as Helminthophila ruficapilla, and 19th century sources use this name. In 1910, the warbler was reassigned to the Vermivora genus.

- In 2010, the Nashville Warbler was reassigned to the Oreothlypis genus, based on molecular evidence. This genus also included the Tennessee Warbler, which also breeds in the Adirondacks, although it is much less common than the Nashville Warbler.

- In 2008, George Sangster, a Dutch ornithologist who specializes in taxonomy, reviewed molecular phylogenetic studies and proposed a new genus – Leiothlypis, which would include the Nashville Warbler (Leiothlypis ruficapilla). The American Ornithological Union rejected the proposal. The proposal was revised, resubmitted, and rejected again. However, the American Ornithological Society finally accepted the new nomenclature in their 2019 supplement to the Check-list of North American Birds.

- The Nashville Warbler has been allowed to retain its species name – ruficapilla – a reference to the chestnut crown patch in adult males, which is usually not visible.

The Nashville Warbler was given its non-scientific name in 1811 by ornithologist Alexander Wilson, who saw the bird in Nashville, Tennessee. Nashville Warblers do not breed in Tennessee, but are sometimes seen there during spring and fall migrations.

There are two geographically separate breeding populations. Our Nashville Warbler is Leiothlypis ruficapilla ruficapilla; it breeds east of the Mississippi River. The other subspecies (Leiothlypis ruficapilla ridgwayi) breeds in the northwestern US and adjacent areas in Canada. The western birds are somewhat brighter in color than our birds.

Nashville Warbler: Identification

Nashville Warblers are small songbirds, but medium-sized in comparison with other Wood Warblers. Nashvilles average 4.75 inches in length, with a 7.5 inch wing span, weighing in at 0.33 ounces. This makes them larger than the tiny Northern Parula (at 4.4 inches in length), but much smaller than the Ovenbird (at 6 inches in length) or Louisiana Waterthrush – the largest of the warblers at nearly 6 inches in length and 0.74 ounces.

Nashville Warblers in most plumages are fairly easily recognized. The main colors to look for are yellow, gray, and olive green.

- The underparts (which are the parts of the bird that birders most often see) are yellow, except for a patch of white at the base of the legs.

- An important field mark to look for is the bright white eye ring.

- Another field mark, distinguishing the Nashville Warbler from some other warblers with yellow plumage, is the fact that Nashvilles lack wing bars.

- The head is gray, with a gray forehead and crown. Nashville Warblers may have a reddish-chestnut crown patch, but this is usually hidden.

- The belly, breast, and throat are yellow with little contrast between the throat and breast. The breast is unstreaked, although Nashvilles that are wet or ruffled can show streak-like mottling.

- This warbler has a plain olive-green back and wings, contrasting with its blue-gray head.

- The fine, pointed bill is dark brown or black. The base of the Nashville's lower bill is somewhat paler, while the tip of the bill is slate or dull brown.

- The legs are dark. The feet are lighter, usually olive-brown or olive-gray.

Males and females look quite similar in all seasons. Unlike some warblers, males do not go through a major color change in the nonbreeding season. Breeding males, however, have more intense, brighter yellow underparts than their female counterparts. The head is a blue-gray, and the chestnut-crown patch (when seen) is more extensive.

Female Nashville Warblers are somewhat paler and duller than adult males, with less contrast between the colors. The female's head is a more muted gray. Females have the same bold eye ring, but their crown patch is less extensive or missing altogether.

Immature Nashville Warblers are similar to adults, with a white eye ring, yellow underparts, and no wing bars. However, they have a brownish wash on the back, and the head is duller with a whitish throat and paler yellow underparts.

Other Wood Warblers which may be confused with Nashville Warblers include the Tennessee Warbler, which also breeds in the Adirondacks but is much rarer than Nashvilles. Breeding male Tennessee Warblers may look similar to female and immature Nashville Warblers, but Tennessee Warblers have a dark eye line and a whitish (not yellow) belly. Also, Tennessee Warblers lack the Nashville's bright white eye ring.

Nashville Warblers: Songs and Calls

Nashville Warblers, like some other warblers, have two songs.

- The commoner song, which is the one most birders will hear and recognize, is a two part song, each consisting of a series of similar syllables.

- The first part is a clear, two-toned sequence; this is followed by a trill, which is lower in key than the first part and usually about half as long. The entire song lasts less than three seconds.

- Eastern and western birds sing a somewhat different song; and there is some regional variation within populations as well.

- The Nashville Warbler's song is somewhat similar to that of the Tennessee Warbler. However, the Tennessee's song has three parts (which can be remembered by noting that there are three syllables in the word name Tennessee), while that of the Nashville (with a two-syllable name) has only two parts.

The Nashville Warbler's main perch song is often transliterated as: "see-pit see-pit see-pit see-pit titi titi titi." Other transliterations include "see-bit see-bit see-bit see-bit see-bit ti-ti-ti-ti" and "see-bit see-bit see-bit see-bit see-bit ti-ti-ti-ti."

Other birders swear by the mnemonic: "pizza-pizza-pizza eat-eat-eat-eat," which is more memorable and accurately captures the Nashville Warbler's song, at least the regional variant sung in the Trilakes area of the Adirondacks. A useful way to link the mnemonic to the bird is to recall that the city of Nashville is actually somewhat famous for its pizza; an October 2018 TripAdvisor list of America's Ten Best Pizzerias included not one, but two, pizza restaurants in Nashville. (The only other US city so honored was, not surprisingly, New York City, which also holds the title of number one in the top ten US Pizza Cities.)

Only male Nashville Warblers sing. Males usually sing in the mid- and lower parts of the under story, in either deciduous or coniferous trees. Singing begins during spring migration in late April and early May and continues through mid- to late July on the Nashville's breeding grounds.

Male singing is continuous throughout incubation. After the young have hatched, singing frequency declines, but then increases again after the young have fledged.

The Nashville Warbler's daily pattern of vocalizing varies, depending on the stage of the breeding cycle. Early in the breeding cycle (late May and June), males tend to sing continuously, from dawn to dusk. By early July, they sing from dawn to noon, intermittently during the afternoon, and then again in the late afternoon to dusk. They then shift to intermittent singing in the morning in mid-July and curtail singing altogether from late July until the start of migration.

The Nashville Warbler's call note has been variously described as a dry chip or a sharp, somewhat metallic tink.

Nashville Warbler: Behavior

The Nashville Warbler has been described as an active bird which is not particularly shy. The western subspecies reportedly bobs or flicks its tail frequently, but this behavior is much less pronounced in our eastern birds. The Nashville's flight reportedly is undulating, with sputtery wing beats.

Nashville Warbler: Migration

Nashville Warblers winter primarily in central and southern Mexico. In contrast to many other warblers (such as Chestnut-sided Warblers, Northern Parulas, and Yellow-rumped Warblers), Nashville Warblers do not fly across the Gulf of Mexico, but migrate across land.

The Nashville Warbler's spring migration starts relatively early.

- Nashville Warblers leave their wintering grounds beginning in March, arriving on their breeding territories in April and May.

- In the Adirondack Park, Nashville Warblers appear to arrive starting in very late April. The pattern of eBird sightings in the six core Adirondack counties (Essex, Hamilton, Warren, Herkimer, Clinton, and Franklin) show the highest number of reports in the last three weeks in May through the entire month of June and the first three weeks of July.

The Nashville Warbler's fall migration begins relatively late, compared to other warblers.

- Nashville Warblers begin leaving their breeding areas in very late August and September, arriving in their winter territories beginning in October.

- In the Adirondacks, Nashville Warblers apparently begin leaving breeding grounds in late summer and early fall. It is difficult to disentangle reports which reflect birds which breed in the Adirondacks and those reflecting birds which are migrating through the area from Canada. The last ten years showed an increased number of reports in late August and early September, possibly of birds transiting the region from more northerly breeding grounds in Canada.

- By mid-October, most Nashville Warblers appear to have left the Adirondack region.

- Most first-year Nashvilles from eastern breeding populations reportedly migrate along the Atlantic coast during fall migration, while adult birds are said to migrate along inland routes.

Nashville Warbler: Diet and Foraging

Like other warblers, Nashville Warblers are insect eaters. They feed almost exclusively on insects and insect larvae, gleaning insects from the tips of branches, the undersides of leaves, and flower tassels. They are often seen foraging in low trees and shrubbery around the edges of the forest. The main items on the menu include flies, beetles, caterpillars, grasshoppers, and aphids.

Nashville Warblers' foraging behavior is described as active, quick, and acrobatic. Nashville Warblers will sometimes catch insects in the air or pluck insects from the ground, eating their prey while perched. Males are said to forage from the mid-story to the canopy. Females forage mid-story and below.

Nashville Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

Nashville Warblers, like the Mourning Warbler, build their nests on the ground. The nest, which is well-concealed, is usually located under brushy vegetation or small trees. The nest is generally build by the female, using grasses, pine needles, and bark. The male stations himself nearby, often singing.

Incubation is mostly done by the female, with the male occasionally bringing food to the female on her nest. The incubation period is 11-12 days. Both parents feed the young in the nest. Young Nashville Warblers fledge 9-11 days after hatching.

In New York State, the second Breeding Bird Survey (2000-2005) reported sightings of nestlings from 30 May to 22 June. Sightings of fledglings were reported from 11 June to 27 August.

Nashville Warbler: Distribution

The Nashville Warbler, which were considered rare in the early 19th century when ornithologist Alexander Wilson discovered it, is now a relatively common warbler. Partners in Flight estimates a global breeding population of 39 million.

Nashville Warblers breed in two separate areas. The eastern population of Nashville Warblers breeds from central Saskatchewan to the maritime provinces in Canada and from northern Minnesota to New England, southward to Pennsylvania and the Appalachian Mountains to northeastern West Virginia in the US. The separate western population breeds in the mountainous Pacific Northwest.

Population trends over the last two centuries reflect changes in one of the Nashville Warbler's preferred habitat: successional forest. Nashville populations increase as areas with second-growth forests increase in the wake of logging activity or abandonment of agricultural land. In areas where early successional forests have matured and brushy old fields have given way to mature forest, Nashville Warblers have declined.

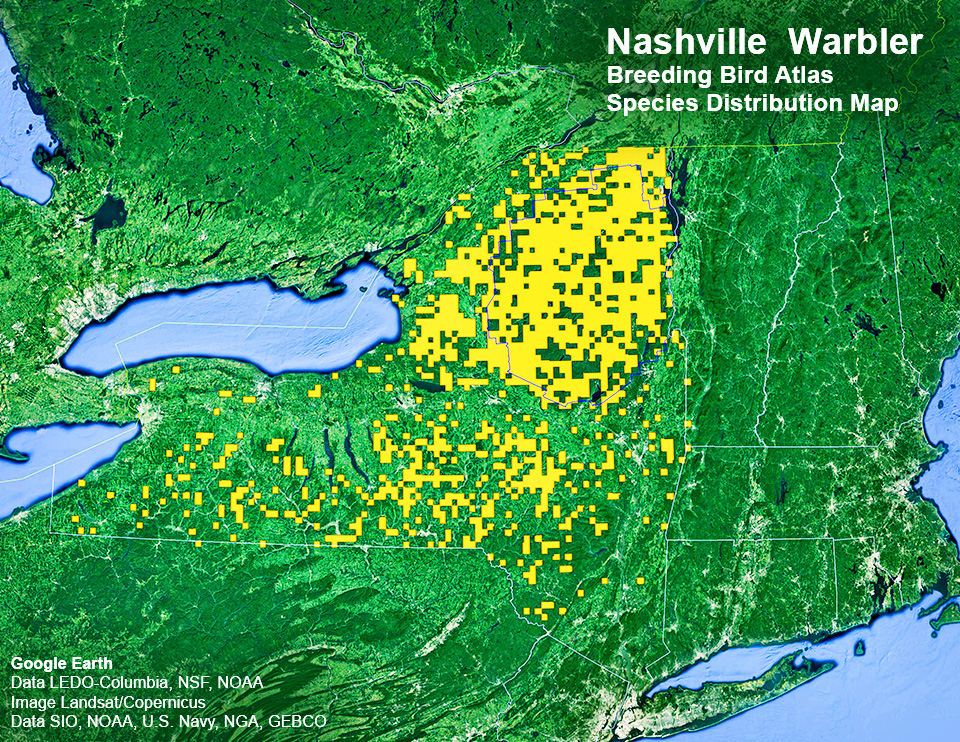

These trends are reflected in Nashville Warbler population changes in New York State, which experienced a 7% decline in blocks with breeding Nashvilles between the two breeding bird surveys.

- The New York State Breeding Bird Survey for 1980 to 1985 found Nashville Warbler breeding populations concentrated in the Adirondack Mountains and Appalachian Plateau area of the state. However, this warbler was present in all ecozones north of the Hudson Highlands (north of New York City). These findings reflect increases in Nashville Warbler populations in the western portions of the state, due to the reversion of farmland and old fields to successional forest, providing suitable habitat for this species.

- The 2000-2005 New York State Breeding Bird Survey showed significant declines in the central and western sections of the state, apparently because the sucessional habitat in this area decreased as the forests matured. However, the northern areas of the state, particularly the Adirondacks, showed significant increases in blocks with breeding Nashville Warblers, with the Champlain Transition area and Tug Hill Plateau also registering increases. These increases are probably linked to increases in the Nashville Warbler's favored habitats. Logging activity in the Adirondack Park continues, creating more successional forests. Beaver activity, meanwhile, continues to create new wetland edges – another preferred Nashville Warbler breeding habitat.

- Results from the first year of the current New York State Breeding Bird Atlas suggest a similar pattern, with most of the confirmed sightings concentrated in the northern part of the Adirondacks.

Nashville Warbler: Habitat

The Nashville Warbler breeds in several different types of habitat.

- In New York State, the highest densities of Nashville Warblers are found at the edges of wetland areas, including bogs, marshes, and swamps.

- Nashville Warblers also breed in higher-elevation forest openings.

- Early successional forests are another preferred habitat for this warbler, which (like the Mourning Warbler) is often seen at the edges of successional deciduous or mixed forest areas with shrubby undergrowth, as well as on the edges of fields.

Ecological communities in New York State where Nashville Warblers are found include both wetlands and non-wetland habitats, such as mountain conifer forests.

- Black Spruce Tamarack Bog

- Dwarf Shrub Bog

- Mountain Fir Forest

- Patterned Peatland

- Sandstone Pavement Barrens

- Successional Northern Hardwoods

For example, one of the Nashville's favored ecological communities is the Dwarf Shrub Bog – a peatland dominated by low evergreen shrubs and peat mosses. The dominant shrub in this ecological community is often Leatherleaf. Other prominent shrubs include Sheep Laurel, Bog Laurel, and Labrador Tea. Bog Rosemary and Steeplebush may also be present, together with stunted trees such as Black Spruce and Tamarack. Characteristic wildflowers include Roundleaf Sundew and Pitcher Plant. Characteristic birds in this community, in addition to Nashville Warblers, include Palm Warblers and Lincoln's Sparrows.

Where to find Nashville Warblers in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Nashville Warblers

- High Peaks Region

- Riverside Drive

- Silver Lake Bog

- Northville-Placid Trail (Long Lake)

- Tahawus

- Northern Region

- Five Ponds Wilderness

- Peavine Swamp

- Massawepie Mire

- Jones & Osgood Ponds

- West Central Region

- Third Lake Creek

- Shallow Lake

- Ferd's Bog

- Wheeler Pond Loop

- Beaver Lake

- Francis Lake

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack birders in search of Nashville Warblers have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the west-central region of the Adirondack Park, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide. Their list of birding sites for Nashville Warblers includes Ferd's Bog and Shallow Lake in Hamilton County, Silver Lake Bog in Clinton County, Massawepie Mire and Peavine Swamp in St. Lawrence County, Jones Pond and Osgood Pond in Franklin County. and the Wheeler Pond Loop in Herkimer County.

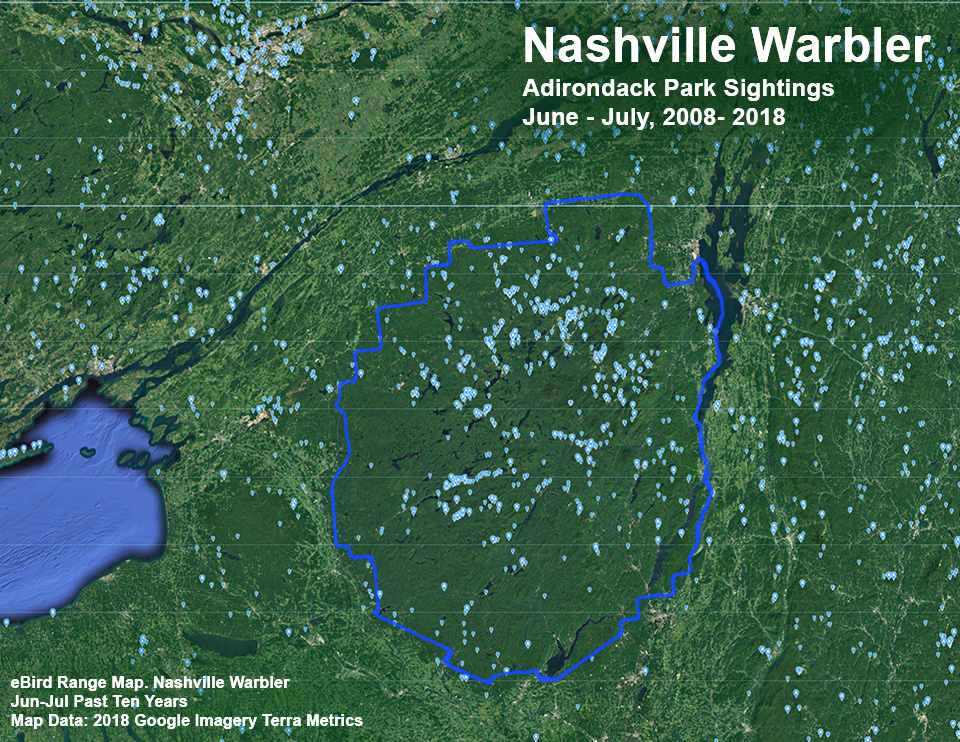

The pattern of eBird sightings for the Nashville Warbler during breeding season is roughly consistent with the Peterson/Lee recommendations and the findings of the two New York State Breeding Bird Surveys.

- Consistent with the findings of the two breeding bird surveys, sightings of the Nashville Warbler reported through eBird are more numerous inside the Blue Line, despite the fact that there are more eBirders outside the Park.

- The list of eBird reports for the Nashville Warbler includes clusters of sightings in popular birding sites, such as Spring Pond Bog, Silver Lake Bog, the Paul Smith's College VIC, Bloomingdale Bog (both the north and south entrances), Ferd's Bog, Moose River Plains, Whiteface Mountain Memorial Highway, Blue Mountain Road, Madawaska Pond, the Roosevelt Truck Trail, Amy's Park, and Massawepie Mire.

Among the trails covered here, the most likely locations to look for Nashville Warblers include the brushy areas on the edges of the fields at the John Brown Farm Trails, any of the trails at the Paul Smith's College VIC that pass through second-growth forest or provide access to forest edges or the edges of wetland areas, early successional habitats and the edges of wetlands along Hulls Falls Road and the Jackrabbit Trail, forest and wetland edges near the Cemetery Road Wetlands, and wetland areas on the Bloomingdale Bog Trail.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Leiothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Nashville Warbler. Leiothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Nashville Warbler. Leiothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of the World. Subscription Web Site. Nashville Warbler. Leiothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Nashville Warbler. Oreothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Warren, Hamilton, Essex, Herkimer, Clinton, Franklin). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton County). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Essex County). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Franklin County). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton, Essex, Franklin). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Fulton, Hamilton, Herkimer, Lewis, Oneida, Saratoga, St. Lawrence, Warren, Washington counties). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Xeno-canto Database. Nashville Warbler. Leiothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

G.A. Gough, J.R. Sauer, and M. Iliff. Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter. 1998. Version 97.1. Nashville warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla. Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

USGS. Longevity Records of North American Birds. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Nashville Warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Nashville Warbler. Leiothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Nashville Warbler. Oreothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map (Google Earth). Nashville Warbler. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 1980-1985. Release 1.0. Updated 6 June 2007. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Nashville Warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 2000-2005. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Nashville Warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

Joan E. Collins, "Nashville Warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla," in Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 476-477.

John M.C. Peterson, "Nashville Warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla," in Robert F. Andrle and Janet R. Carroll (Eds.) The Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 1988). pp. 364-365.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Species Map. Nashville Warbler. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 34.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), p. 97.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), p. 200.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 70-72, 85-87, 98-107, 126-128, 150-152, 158-162, 166-168, 178-180, 181-182, 208-211.

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Trend Estimate by Species. Nashville Warbler. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. Nashville Warbler. Oreothlypis ruficapilla. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013. Population Estimates Database, version 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan. 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States, pp. 110-111. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. Stokes Field Guide to Warblers (Little, Brown, 2004), pp. 17, 20, 22, 24, 29, 58-59.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 17, 23, 24, 29, 33, 35, 37, 43, 45, 218, 262, 266, 348,352, 358, 360-365, 538, 542-543, 547.Chris G. Earley. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 26-29.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 92-97.

Jon Curson, David Quinn and David Beadle. Warblers of the Americas. An Identification Guide (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), pp. 102-103, Plate 2.

Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett. A Field Guide to Warblers of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), pp. 166-174. Plate 5.

Douglass H. Morse. American Warblers: An Ecological and Behavioral Perspective (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 263, 271, 291.

W.W. H. Gunn, "Nashville Warbler. Vermivora ruficapilla," in Ludlow Griscom, Alexander Sprunt, Jr. et al., Eds. The Warblers of North America (The Devin-Adair Company, 1957), pp. 81-83, Plate 6.

Arthur Bent. Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers. Part One and Part Two (Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 203, 1953), pp. 105-116. Kindle Book. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 63-64, 76, 102-103, 124, 125. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Black spruce-tamarack bog. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Dwarf Shrub Bog. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Mountain Fir Forest. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Patterned Peatland. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Sandstone Pavement Barrens. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Nashville Warbler. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Aretas A. Saunders. The Summer Birds of the Northern Adirondack Mountains. Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin. Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 326-499. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Theodore Roosevelt, "The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, N.Y.," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 501-504. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Perley M. Silloway, "Relation of Summer Birds to the Western Adirondack Forest," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 4 (March 1923), pp. 396-486. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 15-16, 20-21, 32-34, 390-392. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

C. Hart Merriam, "Preliminary List of Birds Ascertained to Occur in the Adirondack Region. Northeastern New York," Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, Volume 6, Number 4 (October 1881), pp. 225-235. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

Recognize the parulid genus Leiothlypis. Proposal (453x) to South American Classification Committee. Undated. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

R. Terry Chesser, et al, "Fifty-First Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds," The Auk, Volume 127, Number 3, July 2010, pp. 726-745. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

James A. Jobling. Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names (Christopher Helm, 2010), pp. 283, 314. Retrieved 9 January 2019.