Shrubs of the Adirondacks:

Labrador Tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum)

Labrador Tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) is a low, evergreen shrub that grows in bogs and alpine summits in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. It produces clusters of small, white flowers in June. This species is a member of the Heath Family.

The common name of this species reflects both its abundance in Labrador and its long use as an herbal tea. Labrador Tea is also known as Bog Labrador, Bog Labrador Tea, Rusty Labrador Tea, Muskeg Tea, Country Tea, Indian Tea, James Tea, Marsh Tea, and Swamp Tea. In northern Canada, the plant is known as Hudson's Bay Tea. The name "groenlandicum" is a reference to Greenland, where the plant is common. This species was formerly known as Ledum groenlandicum.

Identification of Labrador Tea

Labrador Tea grows from one to three feet tall. Its bark is coppery-orange to reddish brown. The twigs are densely hairy. The stems are upright. New stems are covered with coppery hairs that gray by second year and persist for number of years. The bark on older wood is gray.

Labrador Tea's aromatic leaves are oblong, tapered or blunt at the ends, clustered on the upper parts of the branches. The thick, leathery leaves are 1 to 2¼ inches long, and ¼ to ⅔ of an inch wide. The leaves are arranged in an alternate pattern, which means that a single leaf is attached at each node.

The smooth edges of the leaves turn downward. The leaves are glossy and green on top. The lower surface of leaves are covered by a dense mat of tangled woolly hairs, which are white on young leaves and rusty orange or brown on mature leaves.

There are several competing theories as to why Labrador Tea and certain other members of the Heath Family have adopted leaves with these features.

- One theory suggests that these features reflect a strategy for reducing water loss. Although the bog is frozen in winter, the plant's evergreen leaves are still exposed to the wind, except during periods of deep snow. The small leaf size, the thickness of the leaf, and the rolled-under margins all help minimize water loss.

- A competing school of thought contends that these features represent an adaptation to nutrient deficiency, not potential water loss.

- A third theory is that the lower growth forms and tough, leathery leaves of plants like Labrador Tea are mainly adaptations to snow and cold.

In any event, the leathery, in-rolled leaves provide convenient clues to Labrador Tea's identity.

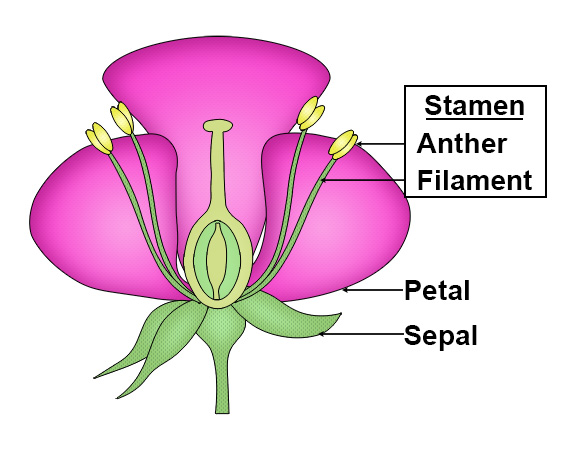

Labrador Team flowers in late spring, producing rounded clusters of ten to forty white flowers. The clusters, which appear at the ends of the stem, are generally 1.5 to 2.5 inches across, while the individual flowers are about half an inch across, with five rounded petals and five to ten slender, conspicuous stamens Stamen: The male part of the flower, made up of the filament and anther. surrounding the small, round green ovary in the center. The tiny white flowers are fragrant and sticky. Buds form in late summer at the tip of the branches. When the flowers bloom in the spring, the brown bud scales fall away.

Stamen: The male part of the flower, made up of the filament and anther. surrounding the small, round green ovary in the center. The tiny white flowers are fragrant and sticky. Buds form in late summer at the tip of the branches. When the flowers bloom in the spring, the brown bud scales fall away.

In the Adirondack region, Labrador Tea normally blooms from early to late June, depending on the weather. Michael Kudish, who tracked bloom dates in the upland regions of the Adirondacks, noted 29 May as the earliest flower date and 12 June as the median date. A review of bloom dates from iNaturalist observations also suggests a bloom period from early to late June or very early July, with early July flowering for higher elevations.

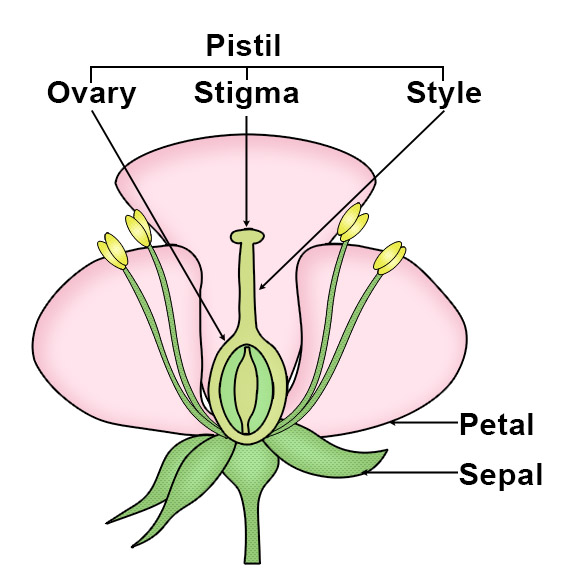

The fruit of Labrador Tea occurs in dropping clusters. The capsules are fuzzy and oval, about a quarter of an inch long, and tipped with a persistent style Style: The narrow, elongated part of the pistil between the ovary and the stigma. The style is part of the pistil (the female organs of a flower), which also consists of an ovary and a stigma. The style is the stalk that connects the stigma to the ovary.. The fruit matures in late summer. In the Adirondacks, the fruit matures starting in August. The fruit splits open when ripe, opening upward from base into five parts.

Style: The narrow, elongated part of the pistil between the ovary and the stigma. The style is part of the pistil (the female organs of a flower), which also consists of an ovary and a stigma. The style is the stalk that connects the stigma to the ovary.. The fruit matures in late summer. In the Adirondacks, the fruit matures starting in August. The fruit splits open when ripe, opening upward from base into five parts.

Keys to identifying Labrador Tea and differentiating it from other leathery-leafed plants growing in swampy or boggy habitats include leaf arrangement, shape, and color, as well as the color and arrangement of the flowers.

- Several features differentiate Labrador Tea from Bog Rosemary. Bog Rosemary's bell-shaped pink flowers are very different from Labrador Tea's clusters of white flowers. In addition, although both plants have alternate leaves, Labrador Tea leaves are bright green on top, while Bog Rosemary leaves have a blue-gray cast.

- Labrador Tea can be distinguished from Sheep Laurel by both the flowers and the leaves. Labrador Tea's cluster of white flowers appears on the end of the stem, while the pink flowers of Sheep Laurel appear a few inches from the top of the stem, with newer leaves above the cluster of flowers. In addition, Sheep Laurel leaves lack the in-rolled edges of Labrador Tea leaves.

- Labrador Tea can be distinguished from Leatherleaf by both the leaves and the flowers. Leatherleaf leaves are not in-rolled like the leaves of Labrador Team. Also, the undersides of Leatherleaf leaves have small brown scales, contrasting with the dense mat of orange-brown hairs on the underside of Labrador Tea leaves. In addition, Leatherleaf leaves become progressively smaller toward the end of the current year's growth. Finally, Labrador Tea's cluster of five-petalled white flowers contrast with the white bell-like flowers of Leatherleaf.

- Labrador Tea's rounded cluster of five-petalled, white flowers are also very different from the cup-shaped pink flowers of Bog Laurel. Although both plants have incurled leaves, Bog Laurel leaves are opposite, in contrast to Labrador Tea's alternate leaves.

Uses of Labrador Tea

Labrador Tea's spicy leaves have been used to make a tasty herbal tea for centuries. A lengthy list of native American groups, including the Algonquin, Potawatomi, and Ojibwa, have used Labrador Tea for this purpose. It should be noted that some sources warn that tea made from the leaves of this species may be toxic in concentrated doses, since it contains toxic alkaloids known to be poisonous to livestock, particularly sheep. The foliage is said to contain grayanotoxins, which affect the heart and could cause neurological problems.

Native Americans also made extensive use of Labrador Tea to treat a wide variety of ailments, including asthma, rheumatism, burns, and diseases of the liver and kidney. For instance, the Algonquin reportedly used an infusion of the plant for headaches and colds. The Chippewa used a powder containing powdered root to apply to burns and ulcers. The Cree used an infusion of the flowers for insect sting pain and rheumatism; they used a poultice of leaves to apply to wounds. The Oweekeno used an infusion of leaves as a remedy for a sore throat.

Wildlife Value of Labrador Tea

Labrador Tea has limited importance to wildlife. Its flowers provide nectar for some butterflies. Moose and White-tailed Deer are known to feed on the foliage, but it is not a preferred browse, probably used only in winter when other food is scarce. Labrador Tea is a larval host for the Northern Blue butterfly.

In addition, the bog communities where Labrador Tea flourishes are extremely important to some bird species, including the Palm Warbler and Lincoln's Sparrow. Palm Warblers reportedly use the woody stems of Labrador Tea as nest material, to construct the outer portion of the cup-shaped nest.

Distribution of Labrador Tea

Labrador Tea can be found in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, south through the New England States, northern New Jersey, mountains of Pennsylvania, the northern Great Lake States, North and South Dakota, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon

Labrador Tea occurs in most counties in the eastern part of the New York State. Vouchered plant specimens have been registered from all of the counties within in the Adirondack Park Blue Line, with the exception of Clinton and Fulton counties.

Habitat of Labrador Tea

Labrador Tea is classified as a wetland plant, but can grow over a wide range of water table depths. In the north country, Labrador Tea grows both on bog mats at low elevations, in mountain conifer forests, and on high-elevation alpine summits. This species is found in several ecological communities in the Adirondack Park, including:

One of the most convenient places to study Bog Laurel is on Barnum Bog, an acidic bog that can be accessed along the Boreal Life Trail boardwalk.

- Labrador Tea typically grows near small, scrubby specimens of Black Spruce and Tamarack.

- Labrador Tea grows alongside other bog-dwelling evergreen shrubs, including Bog Laurel, Bog Rosemary, Leatherleaf, and Sheep Laurel.

- Wildflowers that flourish in this habitat include Cottongrass, Pitcher Plant, Grass Pink, Rose Pogonia, Buckbean, Roundleaf Sundew, and Marsh Cinquefoil, along with sedges and peat moss such as Sphagnum fuscum and Sphagnum magellanicum.

- Birds found in this habitat or on the edge of the bog include the Palm Warbler, Lincoln's Sparrow, Olive-sided Flycatcher, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Cedar Waxwing, and Yellow-bellied Flycatcher.

You can also find Labrador Tea growing along the Bloomingdale Bog Trail, along the marshy shore of Heart Lake, along the Lake Colby Railroad Tracks in Saranac Lake, and on the summits of Adirondack mountains in the High Peaks region, including Marcy, Algonquin, Wright, Iroquois, Coldin, Haystack, Basin, Saddleback, Gothics, Dix, and Whiteface. Plants growing at higher elevations are often stunted.

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), pp. 40, 54, 144.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Labrador-tea. Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) Kron & Judd. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Bog Labrador Tea. Ledum groenlandicum Oeder. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. NRCS National Plant Data Center & the Biota of North America Program. Plant Guide. Bog Labrador Tea. Ledum groenlandicum Oeder. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Flora of North America. Labrador Tea. Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) Kron & Judd. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Labrador Tea. Rhododendron groenlandicom. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) Kron & Judd. Labrador-tea. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Labrador Tea. Rhododendron groenlandicum. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Alpine Krummholz. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Alpine Sliding Fen. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Dwarf Shrub Bog. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Inland Poor Fen. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Mountain Fir Forest. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Open Alpine Community. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Patterned Peatland. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Labrador Tea. Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) Kron & Judd. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Rhododendron groenlandicum (Oeder) Kron & Judd. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Shrubs of Wisconsin. Labrador-tea. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Rhododendron groenlandicum (Labrador Tea). Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Ledum groenlandicum. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

William K. Chapman and Alan E. Bessette. Trees and Shrubs of the Adirondacks: A Field Guide (North Country Books, 1990), p. 96, Plate 24.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958,1972), pp. 287, 364-365.

Doug Ladd. North Woods Wildflowers (Falcon Publishing, 2001), p.185.

Lawrence Newcomb. Newcomb's Wildflower Guide (Little Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 292-293.

Meiyin Wu and Dennis Kalma. Wetland Plants of the Adirondacks. Ferns, Woody Plants, and Graminoids (Trafford Publishing, 2010), p. 66.

Donald D. Cox. A Naturalist's Guide to Wetland Plants. An Ecology for Eastern North America (Syracuse University Press, 2002), p. 90.

Janet Lyons and Sandra Jordon. Walking the Wetlands. A Hiker's Guide to Common Plants and Animals of Marshes, Bogs, and Swamps (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1989), pp. 95-96.

David M. Brandenburg. Field Guide to Wildflowers of North America (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2010), p. 219.

John Kricher. A Field Guide to Eastern Forests. North America (Houghton Mifflin, 1998), pp. 68, 124-125.

Timothy Coffey. The History and Folklore of North American Wildflowers (FactsOnFile, 1993), p. 94.

George W. D. Symonds. The Shrub Identification Book. The Visual Method for Practical Identification of Shrubs, Including Woody Vines and Ground Covers (Quill, 1963), p. 282.

William Carey Grimm. The Illustrated Book of Wildflowers and Shrubs (Stackpole Books, 1993), pp. 530-531.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 268-270.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 97-99.

Plants for a Future. Ledum groenlandicum – Oeder. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), pp. 301-302.

Lee Allen Peterson. A Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Eastern and Central North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977), pp. 208-209.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Revised and Updated. (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 120-121.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Ledum groenlandicum Oeder. Bog Labrador Tea. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birds of North America. Palm Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Cape May Warbler, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher. Subscription web site. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Nancy G. Slack and Allison W. Bell. Adirondack Alpine Summits: An Ecological Field Guide (Adirondack Mountain Club, Inc., 2006), p. 61.

Allen J. Combes. Dictionary of Plant Names (Timber Press, 1994), p. 103.