Trees of the Adirondacks:

Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis)

The Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) – known for its distinctive, golden peeling bark – is a native, deciduous tree that grows throughout New York State and the Adirondack Mountains. Yellow Birch is the third dominant tree of the northern hardwoods and the most valuable of our native birches.

The largest of all the North American birches, the Yellow Birch is also known as Golden Birch, Gray Birch, Silver Birch, and Swamp Birch. The common name – Yellow Birch – refers to the color of the bark.

This tree is very long-lived for a birch, sometimes reaching beyond 100 years. This slow-growing tree may grow to 100 feet, although 50 feet is far more typical. Michael Kudish sampled tree ages in the Paul Smiths area and recorded a Yellow Birch on the Fish Pond Truck Trail that was 235 years old and 36 inches in diameter. Edwin Ketchledge found a 56-inch-diameter specimen near Saranac Lake.

Identification of the Yellow Birch

Yellow Birch bark is bronze or yellowish-gray when the tree is young. The outer layers of the bark peel horizontally in thin, curly, papery strips. As the tree matures, the curls of peeling bark become more abundant and may appear shredded. Once the tree reaches about a foot in diameter, the bronze curls weather off, revealing a thick, platy outer bark, which is irregularly cracked. The inner bark has a wintergreen odor and taste, as do the twigs.

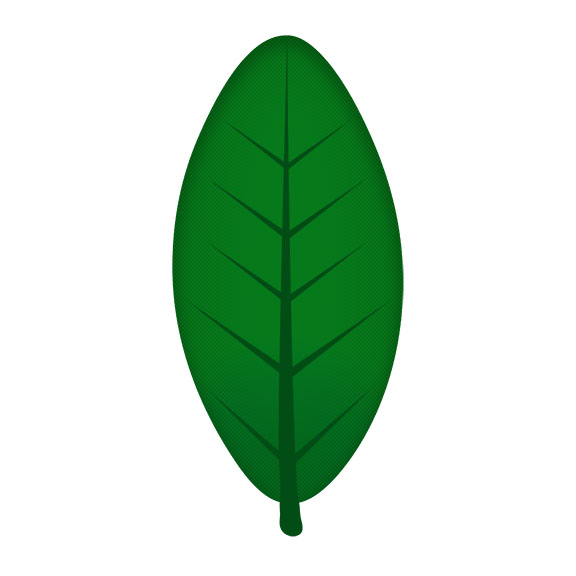

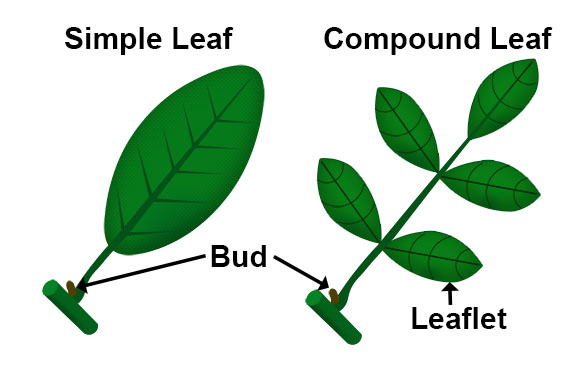

Yellow Birch leaves are elliptical Elliptic: A leaf shaped like an ellipse, widest at the center and tapering at each end., about 2.5 inches wide. The dark green leaves are simple

Elliptic: A leaf shaped like an ellipse, widest at the center and tapering at each end., about 2.5 inches wide. The dark green leaves are simple Simple Leaf: A leaf with a single undivided blade, as opposed to a compound leaf, which is one that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets. and grow in an alternate

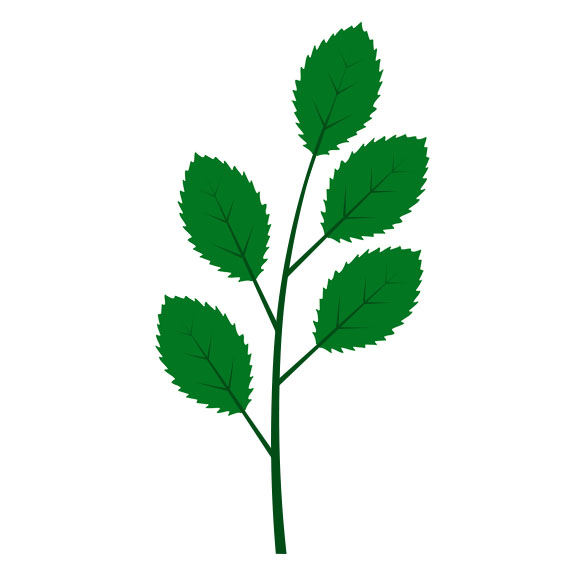

Simple Leaf: A leaf with a single undivided blade, as opposed to a compound leaf, which is one that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets. and grow in an alternate Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem. arrangement, emerging from the stem one at a time. Yellow Birch leaves have a pointed tip and finely double-toothed

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem. arrangement, emerging from the stem one at a time. Yellow Birch leaves have a pointed tip and finely double-toothed Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge. edges. Young leaves are bronze-green, with long hairs beneath. In the fall, the leaves turn bright yellow.

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge. edges. Young leaves are bronze-green, with long hairs beneath. In the fall, the leaves turn bright yellow.

The tree flowers in late May in the Adirondacks. Showy catkinsCatkin: A slim, cylindrical flower cluster with inconspicuous or no petals which appears on some trees and shrubs, including birch and willow. appear just before leaf emergence. The male catkins are long, dropping and yellowish, appearing in cluster of five to eight. The female flowers are ⅝ to ¾ inches long, upright catkins. The fruit, which matures in fall, is composed of numerous, tiny winged seeds packed between the catkin bracts.

The Yellow Birch tree's distinctive peeling bark is the main clue to distinguishing it from other deciduous trees in the Adirondacks. The main difficulty is differentiating Yellow Birch from Paper Birch.

- Both Paper Birch and Yellow Birch feature peeling bark. However, the Paper Birch has bright white bark, the underside of which is a pinkish color. When it peels, the strips are fairly wide, and thick. Yellow Birch bark, by contrast, is more bronze in color; and the bark of the Yellow Birch tends to peel off in thin papery ringlets. This distinction is less helpful in older specimens, when the bark has darkened with age.

- The leaves of Yellow Birch resemble those of the Paper Birch, but are longer and narrower.

- The scent of the stem is another identifier. Scrape a short section of the twig your mystery birch with your fingernail and give it a sniff. If it smells like wintergreen, you probably have a Yellow Birch. Sweet Birch twigs also give off a wintergreen scent, but they are uncommon in the Adirondacks.

Uses of the Yellow Birch

The Yellow Birch is one of the most valuable northern hardwoods in Adirondack forests. The wood is heavy, strong, close- grained, and even-textured. This tree is used for furniture, flooring, cabinetry, charcoal, pulp, interior finish, veneer, tool handles, boxes, wooden-ware, and interior doors. The wood can be stained and takes a high polish. Yellow Birch chips can be used to produce ethanol and other products. The species reportedly was favored by colonial shipbuilders, because its wood was resistant to rot below the waterline.

Yellow Birch has a number of edible uses. Yellow Birch trees can be tapped for sap, which is used to make an edible syrup. The sap is harvested in early spring, before the leaves unfurl, by tapping the trunk. Although the sap flows abundantly, the sugar content is much lower than that of the Sugar Maple. The inner bark of Yellow Birch can be cooked or dried and ground into a powder and used with cereals in making bread. A tea can also made from the twigs and leaves. The wintergreen-flavored twigs and leaves of the Yellow Birch reportedly can be used as condiments.

Yellow birch is little used medicinally, although several native American tribes used it as a treatment for a variety of ailments. For instance, a decoction of the bark is said to have been used as a blood purifier. The Delaware reportedly used a decoction of the bark as a cathartic. The Iroquois reportedly used a decoction as a treatment for skin ailments.

Wildlife Value of the Yellow Birch

Yellow Birch trees are an important plant for wildlife. This species provides food and breeding habitat for a number of birds. The small, upright cones of the Yellow Birch disintegrate slowly and release their seeds as spring approaches, providing a vital food source for wetland birds at a time when many other food sources are scarce. Pileated Woodpeckers, Fox Sparrows, Black-capped Chickadees, Pine Siskin and Common Redpoll are among the bird species which feed on Yellow Birch seeds. Ruffed Grouse feed on seeds, catkins, and buds.

Yellow Birch is a favorite summer food source of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker on its nesting grounds. Sapsuckers create sap wells by pecking and drilling holes in the bark. The result is a series of neat rows of quarter-inch holes spaced closely together around the trunk or limbs. The sapsucker uses its tongue to draw out the sap which fills the holes. Heavy sapsucker feeding can reduce growth, lower wood quality, or even kill both Paper Birch and Yellow Birch.

Yellow Birch trees also provide nesting sites and breeding habitat for a number of Adirondack birds, both permanent residents and summer migrants. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Red-shouldered Hawks, and Boreal Chickadees sometimes nest in Yellow Birch trees. Broad-winged Hawks show a clear preference for Yellow Birch as a nest site in the Adirondack region. The Yellow Birch is a common tree in the breeding habitat for several additional species of birds, including Mourning Warbler, Brown Creeper, and Northern Parula.

Yellow Birch trees are also an important food source for mammals. Yellow Birch is a favorite browse of White-tailed Deer. Deer are said to be especially fond of browsing seedlings during the summer and green leaves and woody stems in the autumn. Moose, Eastern Cottontail, and Snowshoe Hare also use the plant for food. Red Squirrels cut and store the mature catkins and eat the seeds. American Beaver and North American Porcupine chew the bark.

Distribution of the Yellow Birch

The range of the Yellow Birch extends from Newfoundland to northern Minnesota, south through Wisconsin and Michigan to Pennsylvania, and in the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia.

In New York State, the Yellow Birch is found in most of the eastern counties, including those in the Catskills and the Adirondack Mountains, as well as some counties in western New York. Within the Adirondack Park Blue Line, specimens have been documented in all counties except Clinton and Washington.

Habitat of the Yellow Birch

Yellow Birch, which has wider shade and soil tolerances than Paper Birch, is most commonly found in moist woodland. Yellow Birch is intermediate in shade tolerance and can grow in both well-drained and poorly drained sites. In the Adirondacks, Yellow Birch trees are uncommon above 3,000 feet, but are common on moist soil along stream banks, swamps, and slopes.

Yellow Birch is typically a mixed-stand species; it is commonly found in association with other species rather than in pure stands. It is almost universally present in second-growth Adirondack forests. The seeds of the Yellow Birch germinate with difficulty on hardwood litter and thus do best on mossy logs, stumps, and boulders.

Throughout the Adirondack region, Yellow Birch trees may be found in a number of ecological communities:

Look for Yellow Birch along many of trails throughout the Adirondack Park, including virtually all of the nature and hiking trails covered here.

- Common associates of the Yellow Birch in northern hardwood forests include Sugar Maples and American Beech, the two codominants, plus a smaller number of Eastern Hemlock and Red Spruce.

- In the understory, Striped Maple and Hobblebush, mixed with Sugar Maple and American Beech saplings, are found.

- Characteristic wildflowers are Canada Mayflower, Common Wood Sorrel, Wild Sarsaparilla, Partridgeberry, and Foamflower.

- Ferns include Christmas Fern and wood ferns, such as Intermediate Wood Fern.

- Characteristic birds include Red-eyed Vireo, Ovenbird, Black-throated Blue Warbler, and Scarlet Tanager.

Adirondack Tree List

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), pp. 122-123, 248.

E. H. Ketchledge. Forests and Trees of the Adirondack High Peaks Region (Adirondack Mountain Club, 1996), pp. 110-113.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Betula alleghaniensis. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Yellow Birch. Betula alleghaniensis Britton. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. NRCS National Plant Data Center & the Biota of North America Program. Plant Guide. Yellow Birch. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. Silvics of North America. Yellow Birch. Betula alleghaniensis Britton. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Betula alleghaniensis. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

Flora of North America. Betula alleghaniensis Britton. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Betula alleghaniensis. Yellow Birch. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Yellow Birch. Betula alleghaniensis Britt. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 71-72, 75, 107-108, 119-120, 121, 121-122. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Acidic Talus Slope Woodland. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Beech-Maple Mesic Forest. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Northern White Cedar Swamp. Retrieved 29 March 2022..

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 4. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Yellow Birch. Betula alleghaniensis Britton. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Gary Wade et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380, p. 5. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169, p. 6. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

University of Wisconsin. Trees of Wisconsin. Betula alleghaniensis. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

Online Encyclopedia of Life. Betula alleghaniensis. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Winter Deer Foods. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Yellow Birch. Betula alleghaniensis. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Betula alleghaniensis Britt. Yellow Birch. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Plants for a Future. Betula alleghaniensis - Britton. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

Bradford Angier. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Revised and Updated (Stackpole Books, 2008), pp. 22-23.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Mourning Warbler, Brown Creeper, Pileated Woodpecker, American Redstart, Broad-winged Hawk, Boreal Chickadee, Fox Sparrow, Northern Parula. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Black-capped Chickadee, Boreal Chickadees , Broad-winged Hawk, Brown Creeper, Common Redpoll, Fox Sparrow, Mourning Warbler, Northern Parula, Pileated Woodpecker, Pine Siskin, Red-shouldered Hawk, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Ruffed Grouse. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

Paul F. Matray, "Broad-Winged Hawk Nesting and Ecology," The Auk. Volume 91, Number 2 (April 1974), pp. 307-324. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

Ellen Rathbone, "Adirondack Tree Identification 102," The Adirondack Almanack, 18 November 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

Michael Wojtech. Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast (University Press of New England, 2011), pp. 106-107.

William K. Chapman and Alan E. Bessette. Trees and Shrubs of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (Utica, New York: North Country Books, Inc., 1990), p. 30, Plate 8.

Stan Tekiela. Trees of New York. Field Guide. (Cambridge, Minnesota: Adventure Publications, Inc., 2006), pp. 76-77.

Peter J. Marchand. Nature Guide to the Northern Forest. Exploring the Ecology of the Forests of New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine (Boston, Massachusetts: Appalachian Mountain Club Books, 2010), p. 85.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Eastern Trees (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), pp. 100-101, 317.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958,1972), pp. 233-234, 338-339.

Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, and Richard Spellenberg. Trees of Eastern North America (Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 152-153.

C. Frank Brockman. Trees of North America (New York: St. Martin's Press), pp. 104-105.

Keith Rushforth and Charles Hollis. Field Guide to the Trees of North America (Washington, D.C., National Geographic, 2006), p. 109.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Trees. Eastern Region (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980, 1995), Plates 180, 487, 617; pp. 364-365.

Allen J. Coombes. Trees (New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc., 1992), p. 119.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (New York: Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 304-305.

Bruce Kershner, et al. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Trees of North America (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2008), p. 407.

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket. Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1992), pp. 30-31.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Trees (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), p. 156.

Janet Lyons and Sandra Jordan. Walking the Wetlands. A Hiker's Guide to Common Plants and Animals of Marshes, Bogs, and Swamps (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1989), pp. 107-108.

W. T. Doolittle, et al. Birch Symposium Proceedings (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, 1969). Retrieved 19 April 2019.

Samuel P. Shaw, "Management of Birch for Wildlife Habitat," Birch Symposium Proceedings (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, 1969). Retrieved 19 April 2019.

Michael E. Ostry and Thomas H. Nicholls. How to Identify and Control Sapsucker Injury on Trees (U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, 1976). Retrieved 19 April 2019.

Gayne G. Erdmann and Ralph M. Peterson, Jr., "Minimizing Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Damage," in Jay G. Hutchinson, ed. Northern Hardwood Notes (U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, 1992). Retrieved 19 April 2019.