Wildflowers of the Adirondacks:

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra)

Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra (Aiton) Willd.) is a native wildflower that grows in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York and produces white flowers in spring and red berries in summer.

Red Baneberry is a member of the Buttercup Family (Ranunculaceae). It is one of three species in the genus Actaea (Baneberry) found within the Adirondack Park. The other two are White Baneberry and Louis's Baneberry.

- White Baneberry (Actaea pachypoda) is a closely-related plant with very similar leaves and flowers, found in similar upland habitats throughout the Adirondack Park, although its late-summer berries are almost always white, rather than red.

- Louis's Baneberry (Actaea pachypoda × A. rubra = A. ×ludovici B. Boivin) is listed by the New York Flora Atlas as present in Franklin, Essex, Warren, Saratoga, and Oneida counties. This is apparently the same plant that other sources treat as a form of White Baneberry (Actaea pachypoda forma rubrocarpa).

The origin of the genus name (Actaea) is unclear. Some sources suggest that the name is from the Greek word aktea (elder) – a reference to an ancient name for elderberry, although there is little resemblance between elderberry and plants in the Actaea genus. The species name (rubra) is from the Latin for "red" and is a reference to the red berries that appear after flowering. Some older sources use the scientific name Actaea spicata, Actaea spicata var rubra, or Actaea neglecta. The author name (Aiton) is a reference to William Aiton, an 18th century Scottish botanist. The second author name (Willd.) refers to German botanist Carl Ludwig Willdenow (1765-1812).

The term "baneberry" derives from the toxic properties of the plant's berries. Other nonscientific names for Red Baneberry include Snakeberry, Snake-berry, Snakeroot, Red-berry, Poison-berry, Cohosh, Red Cohosh, Western Baneberry, and Necklaceweed.

Identification of Red Baneberry

Red Baneberry is an erect perennialPerennial: An herbaceous plant that lives for more than two growing seasons. Perennial plants grow and bloom over spring and summer, die back every fall and winer, and then return in the spring from their rootstock., between one and three feet high. It grows from rhizomes Rhizome: The modified subterranean stem of a plant that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks. and dies back to the ground in the fall. The central stem is light green.

Rhizome: The modified subterranean stem of a plant that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks. and dies back to the ground in the fall. The central stem is light green.

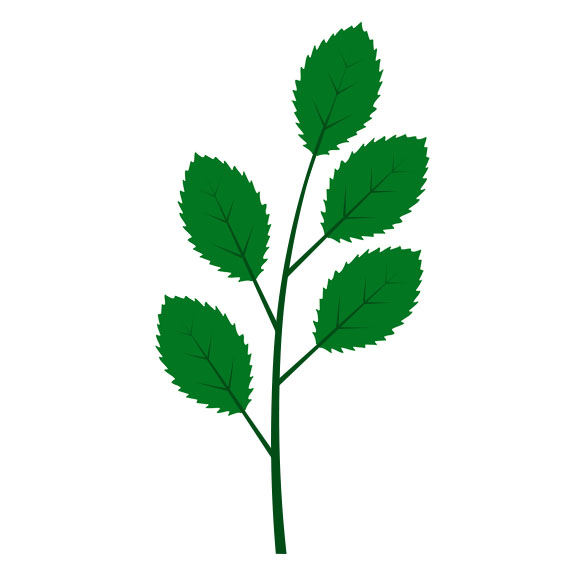

Red Baneberry leaves are alternate Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem., meaning that they emerge from the stem one at a time, not in pairs.

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem., meaning that they emerge from the stem one at a time, not in pairs.

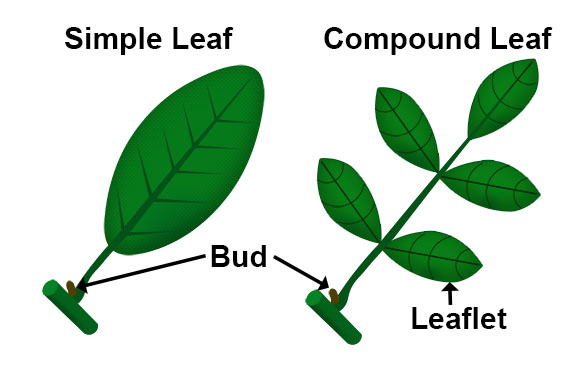

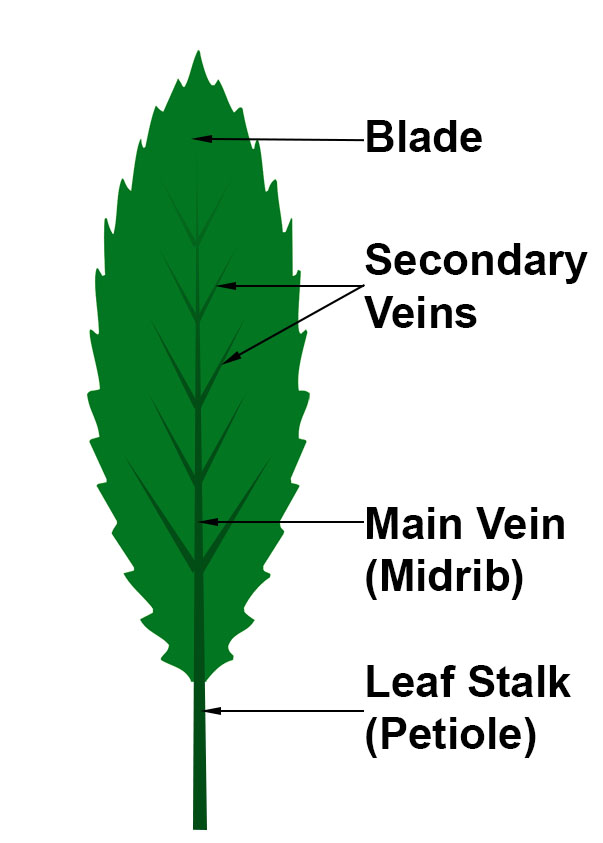

- The leaves are

compound

Compound Leaf: A leaf that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets., which means that each leaf is divided into leaflets. The leaves grow from the upper part of the stems.

Compound Leaf: A leaf that is divided to the midrib, with distinct, expanded portions called leaflets., which means that each leaf is divided into leaflets. The leaves grow from the upper part of the stems. - The leaflets are 1¼–3½" long and oval or oblong.

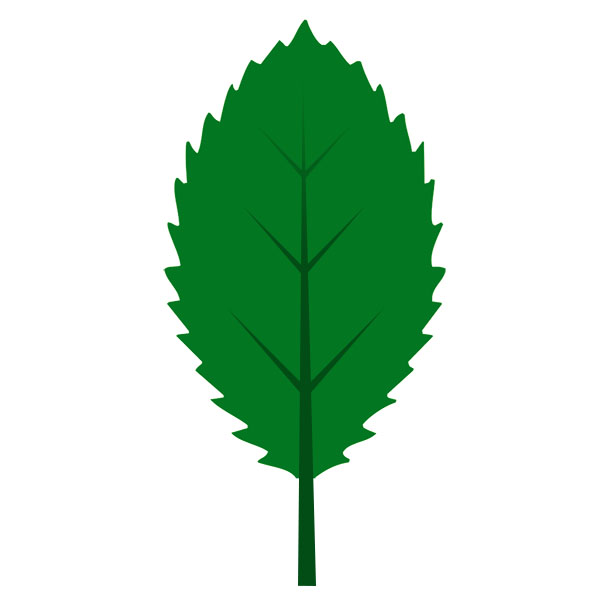

- The

marginsThe structure of the leaf's edge. (edges) of the leaflets are sharply and coarsely

toothed

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge..

Toothed: Leaves which have a saw-toothed edge..

- The upper leaf surface is medium green during the summer and usually hairless, while the lower surfaces of each leaflet are slightly paler and often have some hairs on the veins

Vein: A vessel that conducts nutrients, sugars, and other substances throughout plant tissues; usually associated with leaves. The arrangement of veins in a leaf is called the venation pattern..

Vein: A vessel that conducts nutrients, sugars, and other substances throughout plant tissues; usually associated with leaves. The arrangement of veins in a leaf is called the venation pattern.. - Before dying back in the late fall, the leaves fade from green to yellow with the veins outlined in darker green.

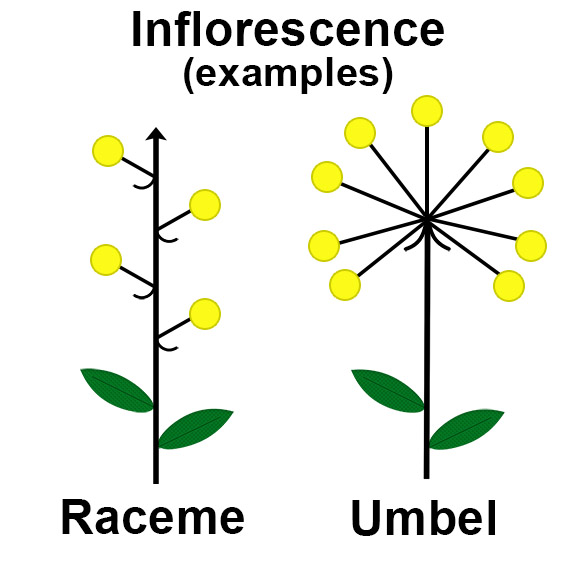

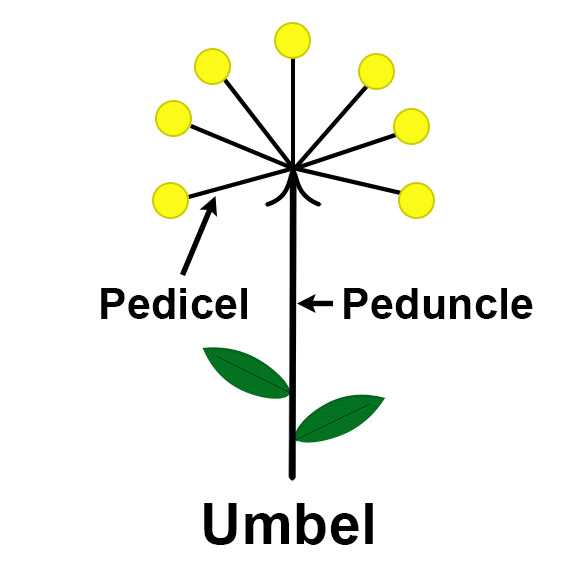

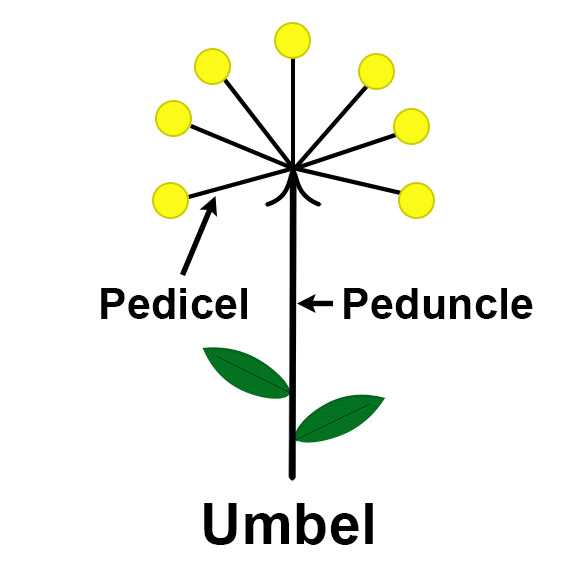

The flowers of Red Baneberry grow in a dense, rounded cluster (inflorescence Inflorescence: A group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem. ) at the end of a long stem that rises above the leaves. There is usually one cluster per stem. The flower cluster is initially cylindrical in shape, about 1½–2" long, but becomes longer when the flowers fade and are replaced by berries.

Inflorescence: A group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem. ) at the end of a long stem that rises above the leaves. There is usually one cluster per stem. The flower cluster is initially cylindrical in shape, about 1½–2" long, but becomes longer when the flowers fade and are replaced by berries.

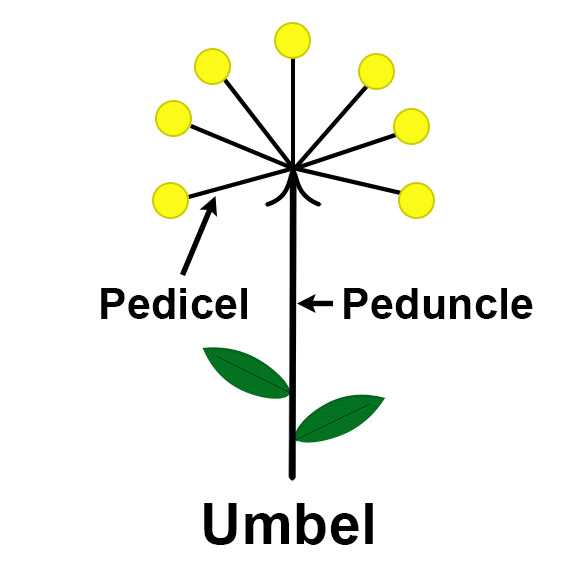

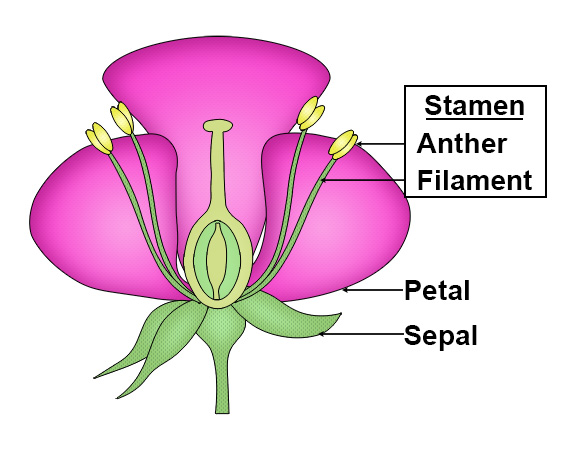

The individual flowers are tiny, about ¼ inch across. Each flower emerges at the end of a short, slender flower stalk (pedicel Pedicel: A small stalk bearing an individual flower in an inflorescence (flower cluster). ) which is about ½" inch long. The slender nature of the flower stalks is not always apparent when the plant begins to flower, but becomes easier to discern when the flower cluster matures. Each flower has 4 to 10 narrow, spear-shaped white petals, which fall off early as the plant blooms, leaving a dozen or more showy white stamens

Pedicel: A small stalk bearing an individual flower in an inflorescence (flower cluster). ) which is about ½" inch long. The slender nature of the flower stalks is not always apparent when the plant begins to flower, but becomes easier to discern when the flower cluster matures. Each flower has 4 to 10 narrow, spear-shaped white petals, which fall off early as the plant blooms, leaving a dozen or more showy white stamens Stamen: The male part of the flower, made up of the filament and anther. with long white filaments and cream anthers

Stamen: The male part of the flower, made up of the filament and anther. with long white filaments and cream anthers.jpg) Anther: the part of a stamen that contains the pollen.. The stamens give each flower cluster a feathery appearance.

Anther: the part of a stamen that contains the pollen.. The stamens give each flower cluster a feathery appearance.

The flowering season for Red Baneberry throughout its range is May to July, lasting from 10-20 days. The timing and duration of the flowering season in the Adirondacks is not known, due to the small number of observations. Most observations suggest a bloom time of late May to early June.

Red Baneberry flowers are replaced by fruit, starting in early summer. The fruit takes the form of berries, which are about ⅓ inch in length.

- In our area of the Adirondacks, the berries start off green in late June or early July, usually changing to greenish white and then red in mid-July and early August as the berries mature.

- The fruit stalk (pedicel

Pedicel: A small stalk bearing an individual flower in an inflorescence (flower cluster).) is slender and green or greenish brown.

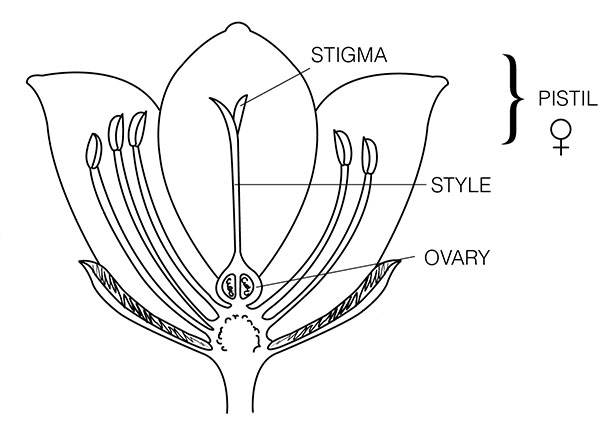

Pedicel: A small stalk bearing an individual flower in an inflorescence (flower cluster).) is slender and green or greenish brown. - The berry has a small dark "eye" in the tip, formed by remains of the stigma

Stigma: part of the pistil, which is the seed-producing, or female, unit of a flower. The stigma is the tip of the pistil, where the pollen lands. .

Stigma: part of the pistil, which is the seed-producing, or female, unit of a flower. The stigma is the tip of the pistil, where the pollen lands. .

- Each berry contains several hard crescent-shaped, dark brown to reddish-brown seeds. Each is about ⅛ inch long.

- The fruit is usually fully mature in our area by the end of August.

Although most Red Baneberry plants bear red berries, there is a white-fruited form. This plant is generally rare, but distinguished from White Baneberry (Actaea pachypoda) by the fact that the fruit stalks are slender and green in color. In some regions, the white-fruited form of Red Baneberry is quite common. The distribution of the white-berried form of Red Baneberry in the Adirondacks is not known, but the absence of reports suggests it is relatively rare.

Red Baneberry is most likely to be confused with a closely related plant: White Baneberry. The latter plant has very similar fluffy white flowers blooming at about the same time. The leaves, which are alternate and compound, are also very similar. In the case of White Baneberry, the berry-like fruit is generally white with a prominent dark eye, as opposed to red. However, as noted above, some specimens of Red Baneberry bear white berries; and (just to complicate matters) some specimens of White Baneberry bear red berries.

The main way of distinguishing the two baneberry species, whether in flower or in fruit, is the thickness of the flower stalk (pedicel Pedicel: A small stalk bearing an individual flower in an inflorescence (flower cluster). ). The flower stalks of White Baneberry are noticeably thicker than the slender flower stalks of Red Baneberry. This difference is most pronounced after the flowers fade and are replaced by fruit. The stalks supporting White Baneberry fruit thicken and turn a bright red, while the stalks of Red Baneberry fruit are significantly more slender (mnemonic: red/slender/scarlet) and remain green or greenish brown. This feature helps distinguish the red form of White Baneberry from Red Baneberry.

Pedicel: A small stalk bearing an individual flower in an inflorescence (flower cluster). ). The flower stalks of White Baneberry are noticeably thicker than the slender flower stalks of Red Baneberry. This difference is most pronounced after the flowers fade and are replaced by fruit. The stalks supporting White Baneberry fruit thicken and turn a bright red, while the stalks of Red Baneberry fruit are significantly more slender (mnemonic: red/slender/scarlet) and remain green or greenish brown. This feature helps distinguish the red form of White Baneberry from Red Baneberry.

There are also less obvious differences between the two species. The berries of Red Baneberry reportedly contain more seeds (ten or more) and smaller seeds than those of White Baneberry. Moreover, Red Baneberry is said to usually have somewhat hairy leaves, while the leaves of White Baneberry are usually hairless. Some sources suggest that the shape of the flower cluster is somewhat different, with those of Red Baneberry rounder than the slightly more elongated flower clusters of White Baneberry. This difference, however, is not definitive as the shape of White Baneberry's flower cluster changes as the flowers mature.

Uses of Red Baneberry

Red Baneberry is not an edible plant. All sources agree that Red Baneberry (like White Baneberry) is poisonous. All parts of the plant are toxic. The berries are considered to be especially poisonous; and large quantities may cause cardiac arrest or respiratory paralysis if consumed. Other symptoms include gastroenteritis, severe stomach cramps, dizziness, headache, diarrhea, vomiting, hallucinations, and circulatory failure.

The toxic properties of Red Baneberry fruit were documented early in the 20th century by an inquisitive researcher who decided to test the effects by ingesting a small number of berries; the result was elevated pulse and burning in the stomach. Undeterred, the investigator waited two days, then doubled the dose to six berries. This produced hallucinations, irregular pulse, heart fluttering, and pain in the abdomen, stomach, and kidneys. The researcher concluded that a dozen berries would probably be a fatal dose.

Despite the plant's toxic properties, it was used at one time by various native American groups to treat a variety of ailments.

- The Blackfoot, for instance, reportedly used a decoction of roots for colds and coughs.

- The Cheyenne use a decoction of roots for sores.

- The Iroquois used an infusion of the roots as a wash for rheumatism.

- Both Native Americans and colonists reportedly used the plant to treat rattlesnake bite.

Wildlife Value of Red Baneberry

Red Baneberry's importance for wildlife is low, because it is normally not an abundant plant. The flowers do not have nectar, offering only pollen to visiting insects. The pollen is collected mainly by bees. Most bees seen on the flowers are Halictid species (including Lasioglossum cressonii and Lasioglossum versans). Other insects that feed on the pollen include several species of flies and beetles. Some flies and beetles are non-pollinating. The main pollinator in the Northeast is said to be the European Snout Beetle (Phyllobius oblongus), an introduced weevil.

Although the fruit is highly toxic to humans, small quantities of baneberry fruits reportedly are consumed by several species of birds, including Ruffed Grouse, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Wood Thrush, Brown Thrasher, Gray Catbird, and American Robin, apparently with no ill effects. Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers and American Robins were observed doing so in the field, while the other species did so in captivity. Several of the species that use Red Baneberry eat the fruit and void the seeds.

Small mammals reportedly also consume the berries. Examples include the White-footed Mouse, Deer Mouse, Eastern Chipmunk, Red Squirrel, and Red-backed Vole. In contrast to birds, small mammals that consume Red Baneberry fruits are said to remove and eat the seeds, leaving the pulp. Baneberry fruit which disappears at night has usually been eaten by rodents.

Distribution of Red Baneberry

The range of Red Baneberry is significantly larger than that of the closely-related White Baneberry. Red Baneberry is found in much of the US and Canada, with the exception of the southern states (including the South Atlantic, East South Central, and West South Central). This plant is listed as Rare in Indiana, Threatened in Ohio, and a plant of Special Concern in Rhode Island

Red Baneberry has been documented in almost all counties throughout New York State. Its presence has been confirmed by vouchered plant specimens in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line. Kudish (1992) noted that the plant was scarce in the Paul Smiths area, but more common in the eastern Adirondacks. This is consistent with the pattern of iNaturalist observations; there have been 28 research-grade observations of Red Baneberry on iNaturalist, mostly in the eastern half of the Adirondack Park.

Habitat of Red Baneberry

Red Baneberry is shade-tolerant and can grow in moderate to full shade, doing best in light to moderate shade. Although is categorized as a Faculative Upland plant (meaning that it usually occurs in upland sites, but can occasionally be found in wetlands), Red Baneberry is said to prefer mesic to dry-mesic forests.

While Red Baneberry often occurs in sites that are somewhat less rich than White Baneberry, the two plants are frequently seen growing in close proximity to one another. Red Baneberry is found in northern hardwood forests, but is also seen in mixed wood forests with conifers.

Among the trails covered here, the most convenient places to look for Red Baneberry are the Big Field Loop and the Bear Cub Loop at Heaven Hill, the Heart Lake Trail, the interpretive trail at the Adirondack Wildlife Refuge, and the Jackrabbit Trail at River Road. Red Baneberry plants are often found growing under hardwoods, such as Yellow Birch and Sugar Maple, near other plants that flourish in northern hardwood forests, such as White Baneberry, Blue Cohosh and Maidenhair Fern.

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 107.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Actaea. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 20197.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra (Aiton) Willd. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

M. F. Crane, "Actaea rubra," Fire Effects Information System (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, 1990). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Flora of North America. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

NatureServe Explorer. Online Encyclopedia of Life. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Margaret B. Gargiullo. A Guide to Native Plants of the New York City Region (New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, 2007), p. 60.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 13. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Actaea rubra. Red Baneberry. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Illinois Wildflowers. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

Illinois Wildflowers. Vertebrate Animal & Plant Database. Actaea rubra. Red Baneberry. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Illinois Wildflowers. Insect Visitors of Illinois Wildflowers. Actaea rubra. Red Baneberry. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Red Baneberry. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Anne McGrath. Wildflowers of the Adirondacks (EarthWords, 2000), p. 9.

Carol Gracie. Spring Wildflowers of the Northeast. A Natural History (Princeton University Press, 2012), pp. 2-4, 243-244.

Roger Tory Peterson and Margaret McKenny. A Field Guide to Wildflowers. Northeastern and North-central North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1968), pp. 54-55. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

Doug Ladd. North Woods Wildflowers (Falcon Publishing, 2001), p. 212.

Lawrence Newcomb. Newcomb's Wildflower Guide (Little Brown and Company, 1977), pp. 424-425.

David M. Brandenburg. Field Guide to Wildflowers of North America (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2010), p. 454.

Timothy Coffey. The History and Folklore of North American Wildflowers (FactsOnFile, 1993), pp. 9-10.

Ruth Schottman. Trailside Notes. A Naturalist's Companion to Adirondack Plants (Adirondack Mountain Club, 1998), pp. 65-68.

William Carey Grimm. The Illustrated Book of Wildflowers and Shrubs (Stackpole Books, 1993), pp. 104-105.

Wilbur H. Duncan and Marion B. Duncan. Wildflowers of the Eastern United States (The University of Georgia Press, 1999), p. 43.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Wildflowers. Eastern Region. (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), p. 722, Plate 114.

William K. Chapman et al. Wildflowers of New York in Color (Syracuse University Press, 1998), pp. 42-43.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), p. 396.

Plants for a Future. Red Baneberry. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Steven Foster and James A. Duke. A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America. Second Edition. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000), p. 57.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Actaea rubra. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Iowa State University. BugGuide. Eupithecia strattonata. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

Steven Clemants and Carol Gracie. Wildflowers in the Field and Forest: A Field Guide to the Northeastern United States (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 384-385.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899). Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Richard S. Mitchell and J. Kenneth Dean. Ranunculaceae (Crowfoot Family) of New York State (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Bulletin Number 446, 1982), pp. 10-13. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

James A. Compton and Alastair Culham, "Neotypification of Actaea pachypoda Elliott (Ranunculaceae)," Taxon, Volume 53, Number 1 (February 2004), pp. 163-165. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

Mary F. Willson, "Natural History of Actaea rubra: Fruit Dimorphism and Fruit/Seed Predation," Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, Volume 110, Number. 3 (July - September 1983), pp. 298-303. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Alice E. Bacon, "An Experiment with the Fruit of Red Baneberry," Rhodora, Volume 5, Number 51 (March 1903), pp. 77-79. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Olle Pellmyr, "The Pollination Biology of Actaea pachypoda and A. rubra (Including A. erythrocarpa) in Northern Michigan and Finland," Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, Volume 112, Number 3 (July - September 1985), pp. 265-273. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Naida L. Lehmann and Rolf Sattler, "Floral Development and Homeosis in Actaea rubra (Ranunculaceae)," International Journal of Plant Sciences, Volume 155, Number 6 (November 1994), pp. 658-671. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

W. J. Hamilton, Jr., "The Food of Small Forest Mammals in Eastern United States," Journal of Mammalogy, Volume 22, Number 3 (August 1941), pp. 250-263. Retrieved 31 October 2019.