Trees of the Adirondacks:

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

The Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) is an evergreen tree that flourishes in moist soil in the Adirondacks of upstate New York. This species is a slow-growing, long-lived tree which may take 250 to 300 years to reach maturity. This tree may reach diameters of four feet and ages of 400 years. The Eastern Hemlock is the only hemlock native to the Adirondack Mountains.

This tree is also known as the Canada Hemlock or Hemlock Spruce. It is a member of the pine family. The common name "hemlock" was reportedly given because the crushed foliage smells a little like that of the poisonous herb hemlock, which is native to Europe.

Identification of the Eastern Hemlock

The Eastern Hemlock has a loose, irregular, feathery silhouette, with fine, lacy twigs whose tips tend to droop gracefully. The root system of this species is shallow, making the tree vulnerable to ground fires, drought, and wind.

This tree has short, flat, blunt, flexible needles, about ½ inch long. The needles are rounded at the tip, dark green above and pale silvery below. The needles have rows of tiny teeth on the margins and appear to grow in flat sprays on the lower limbs of trees. The needles are attached to the twig by tiny slender stalks.

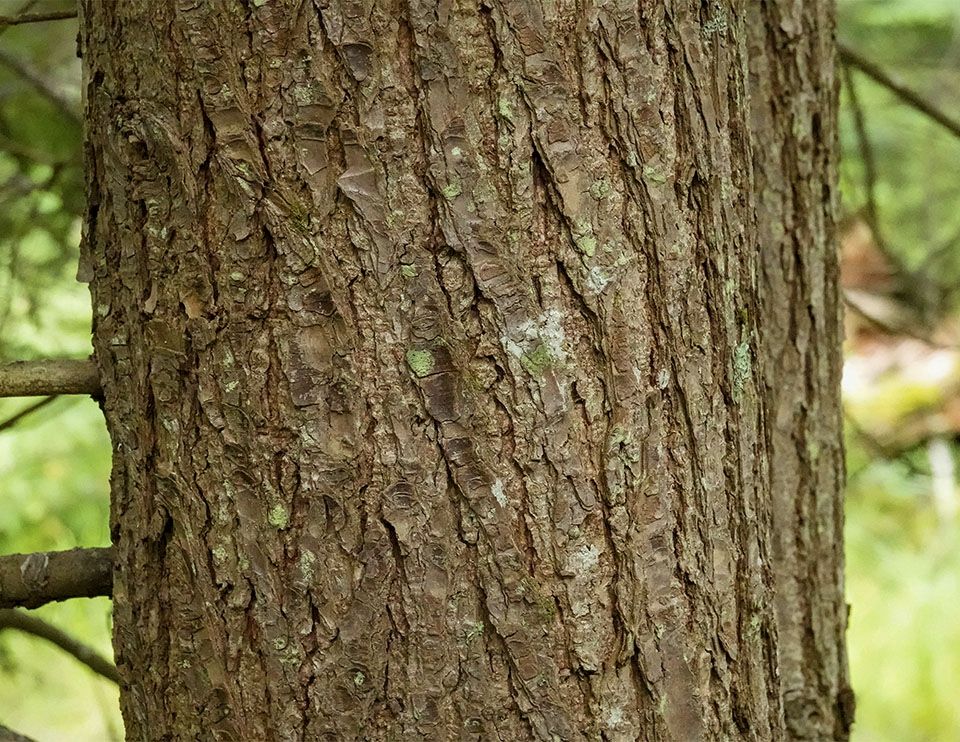

As with many trees, the bark of Eastern Hemlocks changes as the tree matures. When the tree is young, the bark is gray-brown and relatively smooth. As the tree ages, the bark becomes cinnamon brown, with thick, ridges forming flat plates.

Eastern Hemlock bears both male and female flowers. The tree begins to flower at about age fifteen. Male flowers, which appear from April to early June, depending on the locality, appear in light-yellow clusters at the axis of needles from the preceding year. The male flowers are then surrounded by bud scales to form a male conelet.

The shorter female flowers develop on the terminals of the previous year's branchlets; they develop into erect conelets which are pollinated by the wind. After pollination, the conelets are in a drooping position, and the cone scales reclose. The light green cones gradually turn into brown cones (about ¾ inch long) and remain soft and flexible until the seeds are released in the fall. The drooping cones persist through winter.

Keys to identifying the Eastern Hemlock and differentiating it from other coniferous trees include its needles, bark, and habitat.

- Eastern Hemlock trees are easily distinguished from Eastern White Pine, since the latter tree features much longer needles in bundles, while the needles of the Eastern Hemlock grow individually on the twig.

- Eastern Hemlock needles can also be easily differentiated from those of the Red Spruce, which are sharp-pointed and prickly, growing all around the twig. Eastern Hemlock needles are also arranged spirally, but appear to occupy a single horizontal plane. Moreover, Red Spruce needles are four sided, in contrast to the flat needles of the Eastern Hemlock. Finally, the cones of Red Spruce are much larger than those of the Eastern Hemlock.

- The arrangement of Eastern Hemlock needles also contrasts with that of Tamaracks. Tamarack needles are relatively short, like those of the Eastern Hemlock, but are produced in clusters of ten to twenty, as opposed to the single needles of the Eastern Hemlock.

- Eastern Hemlock is also easy to distinguish from Black Spruce, since the latter species thrives in the wettest part of bogs, where Eastern Hemlock does not grow.

Differentiating Eastern Hemlock from Balsam Fir is somewhat trickier.

- Balsam Fir needles, like those of the Eastern Hemlock, are flat and white-lined below. In both cases, the needles appear to occupy a single horizontal plane. However, the needles of the Eastern Hemlock are attached to the twig by tiny slender stalks, in contrast to those of the Balsam Fir, which are not stalked.

- The cones of these two species are very different. Those of the Eastern Hemlock are much smaller and pendant, while those of the Balsam Fir are upright.

- The growth habits of the two species are different. The Balsam Fir is conical, with ascending branches, while the Eastern Hemlock has a loose, feathery silhouette. The topmost shoot of hemlocks tend to droop, in contrast to the conical shape of firs and spruces.

- Eastern Hemlock bark lacks the resin blisters characteristic of the bark of young Balsam Fir trees.

Uses of the Eastern Hemlock

The Eastern Hemlock was used by many native American tribes to treat a variety of ailments, including rheumatism, arthritis, colds, coughs, fever, skin conditions, stiff joints, soreness, and scurvy. Native Americans also used the bark to make dyes and the cambium as the base for breads and soups or mixed it with dried fruit and animal fat for pemmican. Natives and white settlers also made tea from hemlock leaves, which have a high vitamin C content. The plant is still sometimes used in modern herbalism, where it is valued for its astringent and antiseptic properties.

At present, the Eastern Hemlock has more limited commercial uses than some other conifers in the region. The characteristics of hemlock wood limit its use to relatively low-grade products, such as structural lumber, pulpwood, and pallets. Although the bark was once a commercial source of tannin, used in the production of leather, synthetic products are now used in leather production. Hemlock bark is still in demand today, but for landscaping mulch. The Eastern Hemlock makes a poor Christmas tree, since its needles fall upon drying. Its value as firewood is limited by the fact that the wood throws sparks.

One use that the Eastern hemlock has retained is as an ornamental. The tree can be used as a specimen, screen, or group planting, and can be sheared over time into a formal evergreen hedge.

Wildlife Value of the Eastern Hemlock

Eastern Hemlock provides valuable wildlife food and winter shelter. Many species of wildlife benefit from the excellent habitat that a dense stand of hemlock provides. The dense, low branches of young trees provide winter cover for Ruffed Grouse, Wild Turkey, and other wildlife. For example, White-tailed Deer, which have trouble navigating in snow above twenty inches in depth, may yard up in hemlock groves during periods of heavy snow cover.

White-tailed Deer may also consume the foliage and twigs of hemlock as high as they can reach. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation lists hemlock among the "second-choice" plants for winter White-tailed Deer food. Hemlock bark and twigs also provide winter nutrition for Porcupines. The seeds provide food for Red Squirrels, Snowshoe Hares, Deer Mice, Southern Red-backed Voles, and other rodents.

Eastern Hemlocks are also important as a nest site for some species of birds. Blackburnian Warblers have a decided preference for hemlocks as a nest site. Yellow-rumped Warblers, Red-shouldered Hawks, Mourning Doves, Blue Jays, Pine Siskins, Common Grackles, White-winged Crossbills, Bay-breasted Warblers, Magnolia Warbler, American Robins, and Black-throated Green Warblers may also choose this tree as a nest site.

Eastern Hemlock also provides a food source for a number of bird species that breed in the Adirondacks. For instance, White-winged Crossbills are said to feed on the small, winged seeds from Eastern Hemlock cones, as do Northern Flickers, Black-capped Chickadees, Boreal Chickadees, Dark-eyed Juncos, Red Crossbills, American Goldfinch, Evening Grosbeaks, and Pine Siskins.

In addition, the Eastern Hemlock is a common tree species in the breeding habitat of a variety of birds, including:

Black-throated Green Warbler

Blue-headed Vireo

Golden-crowned Kinglet

Northern Parula

Red Crossbill

Red-breasted Nuthatch

White-throated Sparrow

Wood Thrush

Distribution of the Eastern Hemlock

This species is found in the northeastern part of the US, commonly associated with northern hardwoods. In Canada, Eastern Hemlock grows in south-central Ontario, extreme southern Quebec, through New Brunswick, and all of Nova Scotia. Within the United States, Eastern Hemlock occurs throughout New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and the Lake States. The Eastern Hemlock's range extends south in the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia and Alabama and west from the mountains into Indiana, western Ohio, and western Kentucky.

The Eastern Hemlock is found in most counties of New York State. It is present in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line.

Habitat of the Eastern Hemlock

Eastern Hemlock trees are found in conifer forests, mixed conifer/hardwood forests, and northern swamp forests. In the northern hardwood forest, Eastern Hemlock is found on a wide variety of sites, including low rolling hills and glacial ridges.

Eastern Hemlocks, in contrast to Black Spruce and Tamaracks, do not grow in the middle of bogs or marshes. However, they do like moist areas, so look for them in somewhat swampy areas, the dryer edges of bogs, or near the banks of brooks. They can usually be found in mixed stands, with other conifers and hardwoods that are tolerant of moist soils.

In the Adirondack region, Eastern Hemlock may be found in many ecological communities:

- Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest

- Balsam Flats

- Beech-Maple Mesic Forest

- Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp

- Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Northern White Cedar Swamp

- Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest

- Rich Hemlock-Hardwood Peat Swamp

- Rich Shrub Fen

- Rich Sloping Fen

- Spruce-Fir Rocky Summit

- Spruce Flats

- Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest

Look for Eastern Hemlock along the many trails throughout the Adirondack Park that feature mixed wood forests, such as the hemlock-northern hardwood forest – a mixed forest that is typically occurs on cool, mid-elevation slopes and on moist sites at the margins of swamps.

- In such areas, Yellow Birch and Sugar Maple are codominant. Other trees include Red Maple, Eastern White Pine, and Black Cherry. Striped Maple occurs as a midstory tree.

- The shrub layer includes Hobblebush, as well as saplings of canopy trees.

- The forest floor is often densely shaded, so the ground layer is relatively sparse. Characteristic wildflowers include Canada Mayflower, Wild Sarsaparilla, Partridgeberry, Common Wood Sorrel, Jack-in-the-Pulpit, and Starflower.

- Characteristic ferns include Christmas Fern, wood ferns (such as the Intermediate Wood Fern), and Northern Lady Fern, with New York Ferns and Hay-scented Ferns appearing in canopy gaps.

- Birds frequently found in this ecological community include the Blue-headed Vireo, Black-throated Green Warbler, and Blackburnian Warbler.

Prospects for the Eastern Hemlock in the Adirondack Park

The Eastern Hemlock is under severe pressure from the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, an insect pest native to Asia and accidentally introduced to the US. This pest, which leads to decline and mortality within four to ten years, has thrived along the East coast, damaging hemlock forests from Maine to Georgia. Infestations of this pest have been found in 25 counties of New York State, especially in the Hudson Valley and the Finger Lakes.

The insect has not yet spread to the Adirondacks, in part because the main barrier to spread is cold temperatures. There is concern that climate change may help accelerate the spread of the insect, leading to extensive loss of hemlock forests, which would in turn have far-reaching effects on the wildlife species that thrive in the microclimates created by this tree.

Adirondack Tree List

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), pp. 42, 102-103, 248.

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), pp. 42, 102-103, 248.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrière. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers (December 1990), pp. 604-612. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

United States Department of Agriculture. Eastern Hemlock Plant Guide. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrière. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

Flora of North America. Eastern hemlock. Tsuga canadensis (Linnaeus). Retrieved 6 March 2017.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), p. 121. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

Northern Forest Atlas. Images. Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Appalachian Oak-Pine Forest. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Balsam Flats. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Beech-Maple Mesic Forest. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Northern White Cedar Swamp. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Pine-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Hemlock-Hardwood Peat Swamp. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Shrub Fen. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Sloping Fen. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce-Fir Rocky Summit. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 8. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Native Plant Database. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

Minnesota Wildflowers. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Illinois Wildflowers. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Illinois Wildflowers. Vertebrate Animal & Plant Database. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Illinois Wildflowers. Plant-Feeding Insect Database. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

University of Wisconsin. Trees of Wisconsin. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

Online Encyclopedia of Life. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

Plants for a Future. Database. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

The Birds of North America. Swainson's Thrush; Magnolia Warbler; Canada Jay; Yellow-rumped Warbler; Golden-crowned Kinglet; Rose-breasted Grosbeak; Pine Warbler; Baltimore Oriole; Northern Goshawk; Swainson's Thrush; Northern Cardinal; Blackburnian Warbler; Least Flycatcher; Golden-crowned Kinglet; Northern Saw-whet Owl; Wood Thrush; Canada Warbler; Yellow-bellied Flycatcher; Mourning Warbler; Black-throated Green Warbler; Red Crossbill; Northern Waterthrush; Northern Goshawk; Scarlet Tanager; Veery; White-throated Sparrow; Blue-headed Vireo; White-winged Crossbill; Pine Siskin. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Winter Deer Foods. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program. Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

US Fish & Wildlife Service, "New York: Invasive Insect Infestations Spread Further North, Threatening Hemlock Forests," Open Spaces, 24 June 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

Mariko Yamasaki, Richard M. DeGraaf, and John W. Lanier,"Wildlife Habitat Associations in Eastern Hemlock — Birds, Smaller Mammals, and Forest Carnivores," Proceedings: Symposium on Sustainable Management of Hemlock Ecosystems in Eastern North America. USDA Forest Service, 2000. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Theodore Howard, Paul Senak, and Claudia Codrescu, "Eastern Hemlock: A Market Perspective," Proceedings: Symposium on Sustainable Management of Hemlock Ecosystems in Eastern North America. USDA Forest Service, 2000. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

Hugh O. Canham, "Hemlock and Hide: The Tanbark Industry in Old New York," Northern Woodlands, Summer 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Eastern Trees (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), pp. 40-41, 177-178.

George A. Petrides. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958,1972), pp. 4, 21-22, 38-39.

Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, and Richard Spellenberg. Trees of Eastern North America (Princeton University Press), pp. 76-77.

C. Frank Brockman. Trees of North America (St. Martin's Press), pp. 42-43.

Keith Rushforth and Charles Hollis. Field Guide to the Trees of North America (National Geographic, 2006), p. 72.

National Audubon Society. Field Guide to North American Trees. Eastern Region. (Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), Plates 20, 483, pp. 299-300.

Allen J. Coombes. Trees (New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc., 1992), p. 77.

John Kricher. A Field Guide to Eastern Forests. North America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), pp. 62-67, 72-75, 88-90, 126-127.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), pp.290-291. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

Richard M. DeGraaf. Trees, Shrubs, and Vines for Attracting Birds. Second Edition (University Press of New England, 2002), pp. 64-65. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Bruce Kershner, et al. National Wildllife Federation Field Guide to Trees of North America (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2008), p. 118-119.

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket. Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Stackpole Books, 1992), pp. 101-104.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Trees (Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), pp.41-42.