Amphibians & Reptiles of the Adirondacks:

Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta)

The Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) is a freshwater, aquatic turtle with orange or yellow stripes on its neck, legs, and tail. It is found in marshes, ponds, and slow-moving streams.

The Painted Turtle is part of the order Testudines (Turtles). Painted Turtles are members of the family Emydidae (Box and Pond Turtles). This family, which is known for basking in the sun, also includes three other turtles native to the Adirondack Park: Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttatta); Wood Turtle (Clemmys insculpta); and Map Turtle (Graptemys geograpica).

The Painted Turtle belongs to the Chrysemys genus. The genus name is derived from "khrysos" (golden) and "emys" (turtle) – a reference to the yellow stripes on the head. The species name (picta) originates from the Latin for "painted." The Painted Turtle is the state reptile of four states (Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, and Vermont).

Four subspecies of Painted Turtles are currently recognized:

- Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii)

- Southern Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta dorsalis)

- Eastern Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta picta)

- Midland Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata)

Most of the Painted Turtles encountered within the Adirondack Park Blue line are probably Midland Painted Turtles. However, sources conflict on the exact dividing line between the Midland Painted Turtle (with a US range that is generally described as including western New York State and much of Vermont) and the Eastern Painted Turtle (which is generally described as being restricted to the warmer areas closer to the Atlantic Ocean).

- Several sources, including DeGraaf and Rudis (1981) and Carr (1952), provide maps of the subspecies distribution indicating that the Eastern Painted Turtle occurs in the eastern parts of the Adirondack Park, overlapping with the range of the Midland Painted Turtle.

- Other researchers – including Ernst et al (2015), Bishop and Schmidt (1931), Pough and Pough (1968), and Ernst and Ernst (1971) – have explored the intergradation of the two subspecies. One study Hartman (1958) suggests that the zone of intergradation may include parts of the eastern Adirondacks.

- Examination of the 88 research-grade Adirondack Park observations in the iNaturalist data base indicates that virtually all sightings with an image allowing determination of the subspecies point to the Midland Painted Turtle.

In any event, as with many species, recent genetic work has cast doubt on the current taxonomic arrangement of the Painted Turtle. There are suggestions that the Southern Painted Turtle is genetically distinct enough to justify being elevated to a full species, while the genetic variability within the other three subspecies brings into question their status as subspecies.

Painted Turtle: Identification

Painted Turtles are small to medium-sized turtles. Adults are about four to ten inches long. The carapaceCarapace: The dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods (such as crustaceans and arachnids) and vertebrates (such as turtles and tortoises). In turtles and tortoises, the underside of the shell is called the plastro (the top shell) is oval. It is olive to black and relatively smooth, with yellow and red borders. The plastronPlastron: The lower section of the turtle's shell. The upper section is called the carapace. (lower shell) is yellow. The skin is dark with reddish-orange and yellow stripes on the neck, legs, and tail.

The color pattern in the head area is striking. Typically, the turtle will have two side yellow stripes running from the underside of the chin. There are also two yellow spots on either side of the head. The legs and tail also sport bright reddish-orange stripes. The feet are webbed to assist in swimming.

Painted Turtles are sexually dimorphic. Females Painted Turtles are somewhat larger than males. Adult females are 4 to ten inches long, while males are three to six inches long. On average, females weight 18 ounces, compared to the average male weight of 11 ounces. Females tend to have a more rounded top shell. Males have longer and thicker tails and longer foreclaws; the latter feature is used in courtship.

Juvenile Painted Turtles are, of course, much smaller than adults, which makes them much more vulnerable to a variety of predators. The hatchling's shell is more circular, and they have proportionally larger heads, eyes and tails.

Three attributes are commonly used to distinguish the Midland Painted Turtle from the Eastern Painted Turtle:

- The most commonly used is the pattern of the plates (scutesScutes: Horny or bony plates, formed mostly of keratin, covering a turtle's shell. The scute effectively forms the skin over the underlying bony structures.) that cover the top shell. In Eastern Painted Turtles, the vertebral scutesVertebral scutes: The scutes (bony plates) of the carapace which overlie the backbone of the turtle. (the plates that overlie the backbone) are aligned in a more or less straight line with the pleural scutes Pleural scutes: The scutes (bony plates) running along each side of the carapace, next to the vertebral scutes. (the plates running along each side of the shell). In Midland Painted Turtles, the plates are disaligned, or offset from one another, so the seams do not match up.

- The lower shell (plastronPlastron: The lower section of the turtle's shell. The upper section is called the carapace.) of the Eastern Painted Turtle is unmarked or only lightly spotted, while that of the Midland Painted Turtle has a dark, symmetrical marking.

- The Eastern Painted Turtle has wide, light margins on the seams between the plates on its shell, while the margins of the Midland Painted Turtle are narrower and darker.

The problem with using these attributes to sort out the subspecies is that the two subspecies intergrade in parts of their range, including in eastern New York State where the range appears to overlap, so a single specimen may show a mixture of these attributes.

Similar Species: The only other turtle that might be confused with the Painted Turtle is the Northern Map Turtle (Graptemys geograpica), which also has stripes on its head and neck, However, the Northern Map Turtle has markings on its upper shell which resemble the contour lines on a map and shell. These are absent in the Painted Turtle.

Painted Turtle: Behavior

Throughout their range, Painted Turtles emerge from hibernation in March, when water temperatures reach 59 to 64 degrees Fahrenheit. They remain most active through October. Most Painted Turtles are dormant during the winter months; they generally hibernate in the muddy bottoms of ponds, within muskrat lodges or bank burrows, or underneath overhanging dirt banks. Adaptations of blood chemistry, brain, and heart allow them to survive long periods of time without oxygen. Northern populations may hibernate five or six months.

Painted Turtles are diurnal Diurnal: Active during the day, followed by a period of inactivity or sleeping during the night. Nocturnal animals are active primarily at night, while animals that are active in the twilight hours (dawn and dusk) are crepuscular., meaning that they are active during the daylight hours.

- They spend their nights sleeping in the mud on the bottom of their ponds or streams or on a partially submerged object. They become active around sunrise, when they emerge to begin their day basking. After a few hours of basking, during which they warm up enough to become active, they begin foraging in mid-morning. This is followed by another period of basking, after which they resume foraging in the late afternoon and early evening.

- The Painted Turtle's daily activity pattern varies with the season and local climatic conditions. During the summer, they generally have two or three cycles of basking/foraging, with a typical period of basking lasting around two hours. However, on very cool days, they spend most of their time basking; basking ceases on cloudy days. Most basking occurs when cloud cover is zero to 25%.

Basking Painted Turtles use a variety of basking sites, especially half-submerged logs and rocks. They are typically seen basking in groups on a single log, although they may bite or push other turtles in pursuit of a favored place on the log. Basking Painted Turtles sometimes gape, opening their mouth briefly and then reclosing it. When disturbed by a hiker or boater, the entire group of basking turtles will will quickly slip into the water.

Painted Turtle: Diet

The Painted Turtle is an omnivore Omnivore: Animals that eats both plant- and animal-derived food. Carnivores (meaning "meat-eaters" in Latin) are animals that feed on other animals; obligate carnivores (such as members of the cat family) rely entirely on animal flesh, while facultative carnivores supplement their diets with non-animal foods. Herbivores feed exclusively on plants, although some may supplement their diets with small amounts of insects or other animals. , meaning that its menu includes both plants and animals. An analysis of the stomach contents of 76 adult painted turtles taken in 1941 in New York State suggested that the menu was about evenly split between plant and animal material. However, this species is an opportunistic feeder, and this pattern probably varies depending on the availability of food and the population density.

Much of the plant material on the menu is algae. However, Painted Turtles also consume bryophytes and aquatic vascular plants (such as Yellow Pond Lily, White Waterlily, Common Duckweed, and Canada Waterweed).

Painted Turtles also consume a wide variety of animal food. They eat sponges, earthworms, leeches, small clams, crayfish, small crustaceans, water mites, spiders, and insects. Vertebrate foods on their menu include fish (probably consumed as carrion), salamanders (including Eastern Newts), and frogs (including Green Frogs, Pickerel Frog, American Bullfrogs, and Northern Leopard Frogs). They also consume birds (as carrion).

Painted Turtles employ several foraging techniques. They can detect and seize moving prey more readily than prey which is stationary. In some cases, the turtle will make an exploratory strike into vegetation with its head and limbs to force the prey to move; the turtle then takes off in pursuit. Painted Turtles will occasionally ambush their prey. Large prey are held in the jaws, while the turtle uses its forefeet to tear it apart into bite-sized hunks.

Painted Turtles readily consume carrion. Young Painted Turtles consume a higher proportion of animal material than mature turtles. The young turtles become more herbivorous as they mature.

Painted Turtle: Reproduction

Sexual maturity in this species is linked to size, rather than age. Male Painted Turtles generally reach sexual maturity when they are about 3¼ inches long – a length which is usually attained when they are about four years old. Females are sexually mature when they attain a length of 4.4 inches (about 6-7 years). Attainment of sexual maturity occurs later in northern populations.

Courtship and mating among Painted Turtles usually occur from March to the middle of June. The male initiates courtship by slowly pursuing the female. After overtaking her, he turns around to face her and begins stroking her head and neck with his foreclaws. If receptive, the female sinks to the bottom; the male follows and mounts her.

Nesting in northern populations of Painted Turtles takes place during June and July. The female leaves her pond or stream in search of an appropriate nesting site. Painted Turtle females usually dig their nests in loamy or sandy soil in open area with a southern exposure, often fairly near the water's edge. They usually build their nests in late afternoon or early evening. They dig their nests entirely with their hind feet and lay one to 23 eggs. The eggs are elliptical and white or cream in color with a slightly pitted surface. Females generally lay two clutches per year. For northern populations, the mean clutch size is larger, but these turtles tend to produce fewer clutches annually.

Incubation time varies, depending on temperature, but hatching usually takes after at least 65 days. The nickel-sized hatchlings may emerge in September. Hatchlings from eggs laid late in the season overwinter in the nest, emerging the following spring.

Painted Turtle: Distribution

The Painted Turtle is one of the most widely distributed turtles in North America. It is the only North American turtle that ranges across the continent. Its range extends from southern Maine and adjacent Canada across the country to Vancouver Island and British Columbia, south into South Carolina and northern Georgia. In the northeast, it is found in southern Maine, the southern parts of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and most of Pennsylvania.

The Painted Turtle is listed by the IUCN as a species of least concern; its population is considered to be stable. It is one of the most abundant turtle species in North America and is widespread and common to abundant in suitable habitat. The IUCN has concluded that all four subspecies are secure in terms of survival prospects.

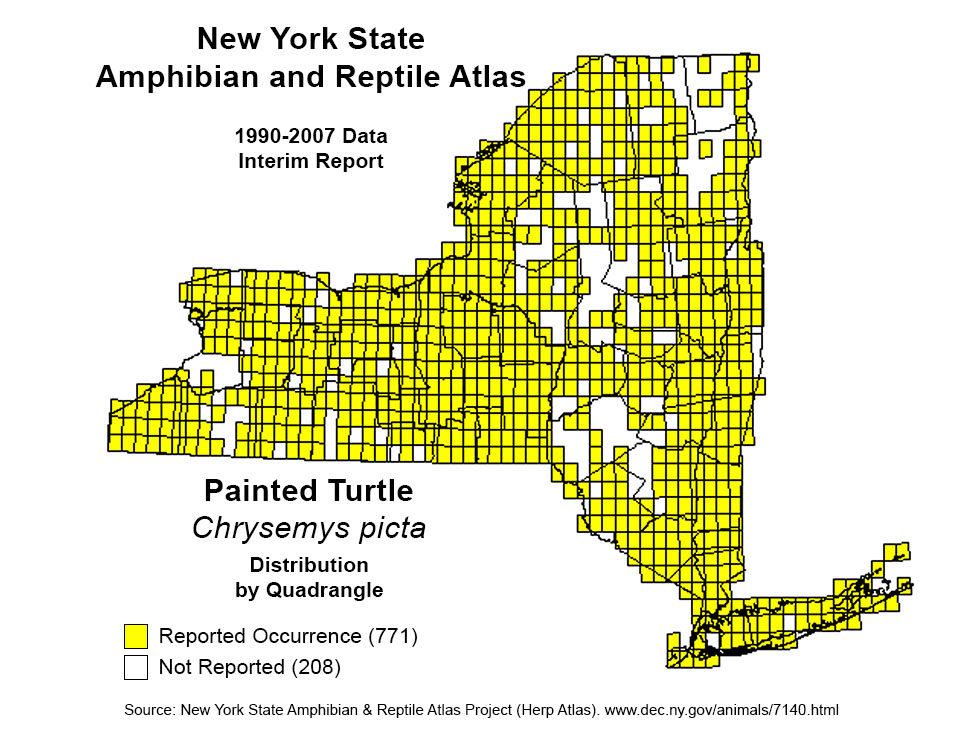

In New York State, Painted Turtles occur throughout the state. Data from the New York Herp Atlas Project indicate that this species has been reported in all counties in the state, including all 12 counties with territory that falls within the Adirondack Park Blue Line.

Material from iNaturalist generally confirms findings from the Herp Atlas. The geographical distribution of iNaturalist sightings within the Adirondack Park Blue Line indicates that the Painted Turtle is one of the most frequently observed turtles within the Adirondack Park. With 88 research-grade sightings, it second only to the Snapping Turtle (125 observations) in numbers of turtle observations. The geographical pattern is also consistent with the Herp Atlas, suggesting that this species is widely distributed throughout the Adirondack Park

Painted Turtles are a long-lived species, with some individuals surviving for thirty to forty years. Nest predation is a major source of mortality. Raccoons are the major threat to nests, hatchlings, and adults. Painted Turtle eggs and hatchlings also fall prey to red ants, Common Gartersnakes, Eastern Chipmunks, Gray Squirrels, skunks, and foxes. Young Painted Turtles are in danger from fish, Snapping Turtles, American Bullfrogs, Opossums, and Minks. Adults may also be taken by birds or prey and North American River Otters. Human causes of mortality include habitat destruction, pesticides, and vehicles.

Painted Turtle: Habitat

Painted Turtles are an aquatic species that can be found in almost every aquatic habitat in the Northeast. These turtles prefer slow-moving, shallow-water habitats and usually avoid waters with fast currents. Painted Turtles are found in marshes, slow moving streams and rivers, shallow ponds, and the shallow, marshy edges of lakes. They thrive in habitats with muddy bottoms, dense aquatic vegetation, and prime basking sites. They reportedly tolerate some industrial pollution. In the Adirondacks, they can be found in a variety of aquatic and wetland ecological communities including vernal pools and deep emergent marshes.

Look for Painted Turtles basking in groups on logs, branches, stumps, or rocks in permanent bodies of water, including ponds and slow-moving streams. They are most frequently seen on sunny days. Among the trails covered here, the best place to see Painted Turtles is on the Black Pond Outlet from the Black Pond Trail and on Heron Marsh from any of the trails that skirt the perimeter of the marsh at the Paul Smith's College VIC. They can also be found near the marsh along the south end of the Bloomingdale Bog Trail.

List of Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles

References

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project. Species of Turtles Found in New York. Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Nature Explorer. Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

iNaturalist. Nonscientific name. Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Midland Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta ssp. Marginata. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Turtles of New York. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wildlife Exposure Factors Handbook. Volume 2. Office of Research and Development. EPA/600/R-93/187 (December 1993). p. 381-406. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. SSAR North American Species Names Database. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Scientific Name. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 47-48, 70-71. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Deep Emergent Marsh. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Vernal Pool. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

Elizabeth H. Thompson and Eric R. Sorenson. Wetland, Woodland, Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont (University Press of New England, 2000), pp. 344-347. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

NatureServe Explorer. Terrestrial Ecological System. Laurentian-Acadian Freshwater Marsh. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

Malcolm L. Hunter Jr., John Albright, and Jane Arbuckle, Eds. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Maine. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station. Bulletin 838 (1992), pp. 101-104. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), pp. 176-177, 190-191, 197-198.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 278-283. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 8-11, 40-46.

James P. Gibbs, Alvin R. Breisch, Peter K. Ducey, Glenn Johnson, John L. Behler, Richard C. Bothner. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New York State. Identification, Natural History, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 38-46, 170-173.

James M. Ryan. Adirondack Wildlife. A Field Guide (University of New Hampshire Press, 2008), p. 106.

Arthur C. Hulse. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Cornell University Press, 2001). pp. 69-70, 200-207, 226. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution (University Press of New England, 2001), p. 52. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Deborah Rudis. Forest habitat for Reptiles & Amphibians of the Northeast (US Department of Agriculture. Forest Service, 1981), pp. 151-153. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John L. Behler and F. Wayne King. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), pp. 450=451, Plates 293, 294, 297.

Thomas F. Tyning. A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles (Little, Brown and Company, 1990), pp. 171-179. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Ontario Nature. Reptiles and Amphibians. Midland Painted Turtle. Chrysemys picta marginata. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

Ross MacCulloch. The ROM Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of Ontario (McClelland & Stewart, 2002), p. 110-111.

Carl H. Ernst and Jeffrey E. Lovich. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Second Edition. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), pp. 184-211.

Carl H. Ernst and Roger William Barbour. Turtles of the World (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), pp. 201-203. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

Archie Fairly Carr. Handbook of Turtles. The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California (Comstock Pub. Associates, 1952), pp. 213-234. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

Carl H. Ernst and Roger William Barbour. Turtles of the United States (The University Press of Kentucky, 1972). Retrieved 21 April 2020.

Carl H. Ernst, John M. Orr, Arndt F. Laemmerzahl, and Terry R. Creque, "Variation and Zoogeography of the Turtle Chrysemys picta in Virginia, USA," Herpetological Bulletin (January 2015), pp. 9-15. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

Carl H. Ernst and Evelyn M. Ernst, "The Taxonomic Status and Zoogeography of the Painted Turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Pennsylvania," Herpetologica, Volume 27, Number 4 (December 1971), pp. 390-396. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

Wilbur L. Hartman, "Intergradation between Two Subspecies of Painted Turtle, Genus Chrysemys," Copeia, Volume 1958, Number 4 (22 December 1958), pp. 261-265. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

F. Harvey Pough and Margaret B. Pough, "The Systematic Status of Painted Turtles (Chrysemys) in the Northeastern United States," Copeia, Volume 1968, Number 3 (31 August 1968), pp. 612-618. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

Sherman C. Bishop and F. J. W. Schmidt, "The Painted Turtles of the Genus Chrysemys," Field Museum of Natural History. Zoological Series, Volume 18, Number 4 (18 June 1931). Retrieved 24 April 2020.

Katherine M. Wright and James S. Andrews, "Painted Turtles (Chrysemys picta) of Vermont: An Examination of Phenotypic Variation and Intergradation," Northeastern Naturalist, Volume 9, Number 4 (2002), pp. 363-380. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

Edward C. Raney and Ernest A. Lachner, "Summer Food of Chrysemys picta marginata, in Chautauqua Lake, New York," Copeia, Volume 1942, Number 2 (10 July 1942), pp. 83-85. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

Elaine Christens and J. Roger Bider, "Nesting Activity and Hatching Success of the Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) in Southwestern Quebec," Herpetologica, Volume 43, Number 1 (March 1987), pp. 55-65. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

Owen J. Sexton, "Spatial and Temporal Movements of a Population of the Painted Turtle, Chrysemys picta marginata (Agassiz)," Ecological Monographs, Volume 29, Number 2 (April 1959), pp. 113-140. Retrieved 26 April 2020.