Birds of the Adirondacks:

Magnolia Warbler (Setophaga magnolia)

The Magnolia Warbler (Setophaga magnolia) is a black and yellow songbird that breeds in dense conifers, particularly second-growth spruce trees.

The Magnolia Warbler is a member of the New World Warbler or Wood Warbler family (Parulidae). Wood warblers subsist mainly on insects during breeding season and are primarily foliage gleaners, with slender, pointed bills. There are about 120 species in the wood warbler family, currently divided into 18 genera. The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (2008) lists 33 warbler species (plus one hybrid) that breed in New York State; 29 are listed as possible, probable, or confirmed breeding birds in the Adirondack Park. All are migratory. Most arrive in the Adirondack Mountains in late April or early May and depart in September or October.

- The Magnolia Warbler is currently assigned to the Setophaga genus, a large group which includes many other warblers that breed in the Adirondacks, including the Palm Warbler, Cape May Warbler, Northern Parula, Blackburnian Warbler, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Pine Warbler, Blackpoll Warbler, and Yellow Warbler. The name Setophaga is derived from the Greek ses ("moth") and phagos ("eating").

- The Magnolia Warbler was previously assigned to the Dendroica genus. In 2011, as part of a larger rearrangement of Wood Warbler taxonomy, based on DNA studies, the Dendroica genus was merged with the Setophaga genus, which now contains at least 33 species. Older publications list the Magnolia Warbler as Dendroica magnolia.

Both the species name (magnolia) and the nonscientific name – Magnolia Warbler – trace back to 1810, when ornithologist Alexander Wilson collected a warbler from a magnolia tree in Mississippi. Wilson apparently recommended the more descriptive name "Black-and-Yellow Warbler," and some 19th century sources lists the species by that name. However, the inappropriate "Magnolia Warbler" is the name in use today. Some early sources list the scientific name as Dendroeca maculosa.

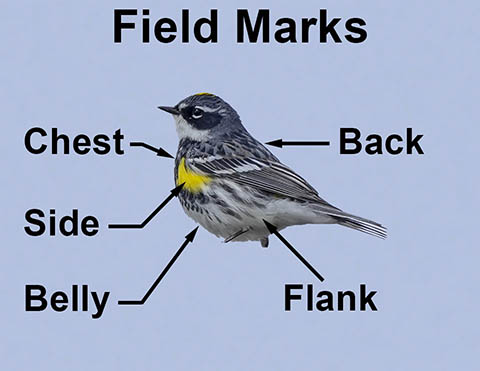

Magnolia Warbler: Identification

Magnolia Warblers are small songbirds; they are about 5 inches in length from the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail, with a wing span of 7.63 inches. The average weight is 0.32 grams. Compared to other warblers that breed in our area, the Magnolia Warbler is about average, larger than the tiny Northern Parula (at 4.4 inches in length), but much smaller than the Ovenbird (at 6 inches in length) or Louisiana Waterthrush (at nearly 6 inches in length and 0.74 ounces).

Magnolia Warblers in all plumages have a unique tail pattern. They have a black and white tail which, from the underside, looks like the tip was dipped in black ink. This tail pattern is diagnostic and fairly easily seen, since this species likes to fan its tail. The rump is yellow or yellowish in all plumages, but this feature is less easily seen. Like several other warblers, Magnolia Warblers look significantly different in the fall, contributing to a phrase frequently invoked by frustrated birders: "confusing fall warblers."

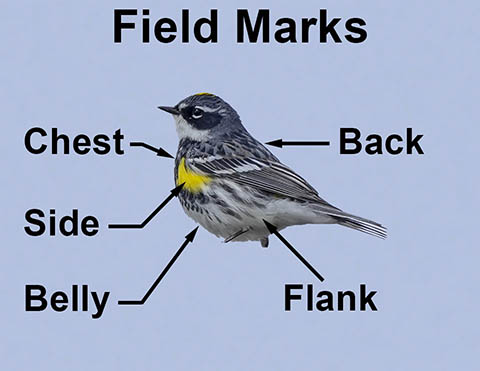

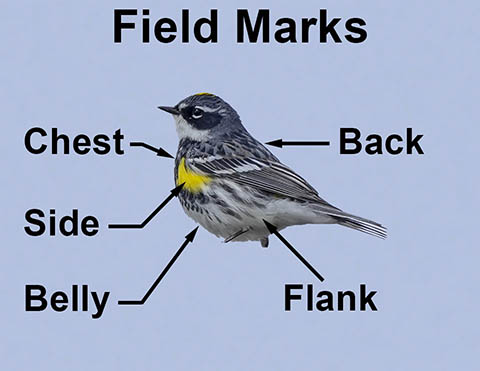

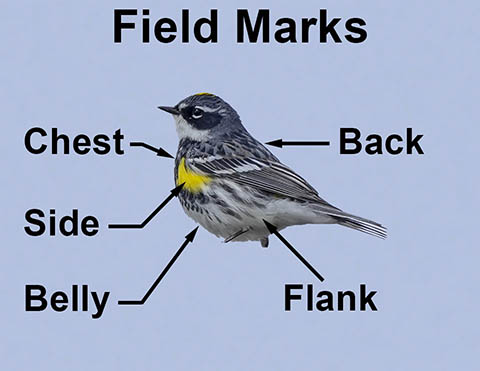

Breeding Males: Male Magnolia Warblers in breeding plumage are the easiest to identify. They are bright yellow and black, with a bold black necklace, a prominent black mask, bluish gray forehead and crown, and a large white wing patch. The male's facial pattern is complex with a white under eye arc and a white swoosh starting at the eye and extending back. They also have distinctive black streaking radiating down the chest from their black neck band. The throat and belly Belly: The topographical region of a bird's underparts between the posterior end of the breast and the vent. are yellow. The upper parts of the bird are gray and black, with a small yellow rump patch.

Belly: The topographical region of a bird's underparts between the posterior end of the breast and the vent. are yellow. The upper parts of the bird are gray and black, with a small yellow rump patch.

Fall males are duller. The streaking is less noticeable, and the wing patches are reduced to two white wing bars. The fall male lacks a black face mask; its face is gray with a white eye ring. Like other Magnolia Warblers, both breeding and fall males have the distinctive black-tipped tail.

Breeding Females: Adult female Magnolia Warblers in breeding plumage are paler than their male counterparts, with a fainter face pattern and less black on the back. They have yellow underparts, with subdued streaking on the flanks Flank: The lateral area posterior to the side region, lying below the pelvis and extending back to the base of the tail. and chest

Flank: The lateral area posterior to the side region, lying below the pelvis and extending back to the base of the tail. and chest Chest: The chest (also called the breast) is the upright part of the bird’s body between the throat and the abdomen. . The breeding female's head is gray, with white eye rings. She has a faint gray band across the neck and thinner white wing bars.

Chest: The chest (also called the breast) is the upright part of the bird’s body between the throat and the abdomen. . The breeding female's head is gray, with white eye rings. She has a faint gray band across the neck and thinner white wing bars.

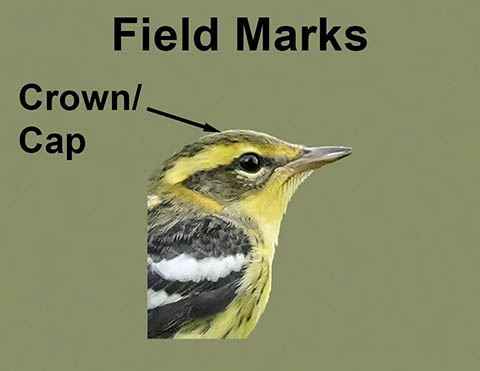

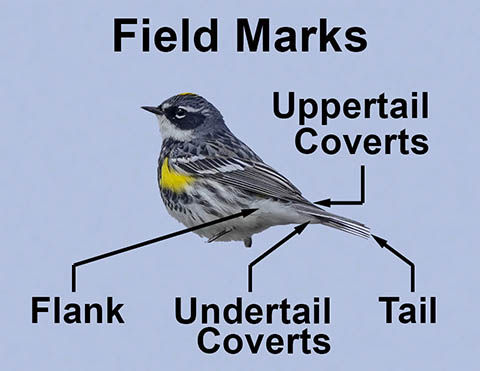

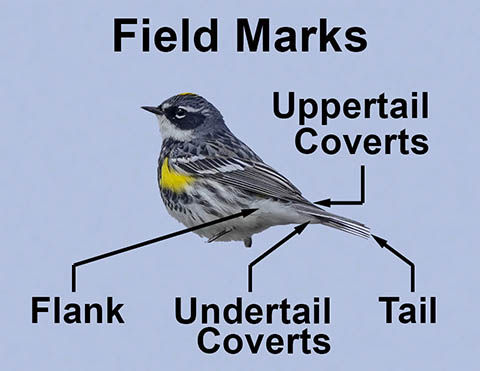

Immatures: Immature Magnolia Warblers resemble the female, but are duller overall and lack the black streaking on the chest. The crown Crown/cap: The top of a bird's head. Some birds have a central crown stripe. and upper parts are olive-gray. The throat, flanks, and belly

Crown/cap: The top of a bird's head. Some birds have a central crown stripe. and upper parts are olive-gray. The throat, flanks, and belly Belly: The topographical region of a bird's underparts between the posterior end of the breast and the vent. are yellow. The immature bird has white undertail coverts

Belly: The topographical region of a bird's underparts between the posterior end of the breast and the vent. are yellow. The immature bird has white undertail coverts Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail., with the Magnolia Warbler's distinctive black-tipped tail.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail., with the Magnolia Warbler's distinctive black-tipped tail.

Similar Species: There are several other birds that are somewhat similar in coloring to the Magnolia Warbler.

- The adult male Canada Warbler is somewhat similar to the adult male Magnolia Warbler. Canada Warblers, however, have clean gray wings without wing bars, and their backs are unstreaked gray, contrasting with the black or streaked backs and large white wing patches of the Magnolia Warbler. Adult female and immature Canada Warblers could also be confused with Magnolia Warblers. However, the Canada Warblers lack the Magnolia Warbler's wing bars. In addition, Canada Warblers in all plumages lack the Magnolia Warbler's tail dipped in black.

- Adult male Prairie Warblers are somewhat similar to Magnolia Warblers, but they have a yellow head in contrast to the Magnolia Warbler's gray head and lack the Magnolia's black face mask. Moreover, Prairie Warblers have yellowish wing bars, in contrast to the white wing bars of the Magnolia Warbler. Prairie Warblers are fairly rare in the Adirondack Park.

- American Redstarts also have a distinctive T-shaped tail pattern with a black tip. However, the American Redstart has yellow or orange in the tail (in contrast to the white tail marking of the Magnolia Warbler). Moreover, the American Redstart lacks the Magnolia's yellow chest and dark streaks.

- The Northern Parula lacks side streaking and the black tail band. Its breast has more limited yellow, and the bill is bicolored.

- The Nashville Warbler is smaller and more active than the Magnolia Warbler. It lacks the Magnolia's wing bars and has a greenish back contrasting with a blue-gray head. Its undertail coverts

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are yellow, and its tail is dark, in contrast to the Magnolia Warbler's black-tipped white tail. The Nashville Warbler also lacks the Magnolia Warbler's chest streaking.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are yellow, and its tail is dark, in contrast to the Magnolia Warbler's black-tipped white tail. The Nashville Warbler also lacks the Magnolia Warbler's chest streaking. - The Kirtland's Warbler also has yellow underparts with streaking, but lacks the Magnolia Warbler's breast band and white tail dipped in black. In any event, the Kirtland's Warbler is one of the rarest songbirds in North America and has a very restricted range. It breeds only in Jack Pine habitat in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ontario; and its migration route does not take it through the Adirondacks.

Magnolia Warbler: Songs and Calls

Male Magnolia Warblers, like some other warbler species, have several different songs. In the case of the Magnolia Warbler, the songs are somewhat similar. The songs are about a second or two long and rather musical. Many birders find the following mnemonics useful as a guide: "wheet-wheet'eo" or "weeta-weeta-weetsee." The Magnolia Warbler's songs are usually softer than those of the Winter Wren or Red-eyed Vireo, both famous for their loud, incessant singing during the breeding season.

The Magnolia Warbler song variant with an accented ending reportedly is given during courtship and around the nest. The less-accented version is said to be used mainly in territorial defense and sung more often at dawn and dusk.

Male Magnolia Warblers begin singing during spring migration and after they arrive on their breeding grounds. They continue singing throughout the summer, beginning very early in the morning and continuing throughout the day until dusk. The frequency of singing declines after about 10:00 AM. Singing apparently continues until the bird leaves for its wintering grounds in August. One early 20th century observer reported that the average date of last singing in Allegany Park in western New York was 1 August.

The singing pattern of a Magnolia Warbler monitored in 2019 in the High Peaks area of the Adirondack Park illustrates this pattern. This bird began singing regularly in very early June. He usually started ten or fifteen minutes before sunrise. He continued singing throughout the day (with peaks in the early morning and at dusk) until the very end of July. By then, his song frequency had declined significantly, at a time when the indefatigable Winter Wren and Red-eyed Vireo were still singing constantly.

Magnolia Warblers use several different kinds of call notes. The call note used by both male and females is a long, nasal "zic." The flight note is a high, buzzy "zee."

Magnolia Warbler: Behavior

Magnolia Warblers are moderately active. They are usually seen in the lower to mid-story, in contrast to Blackburnian Warblers, who tend to stay high in the treetops. Like Blackburnian Warblers, Magnolia Warblers move around by hopping on arboreal vegetation while feeding. The Magnolia Warbler's flight has been described as tacking and undulating, with sputtery wing beats. One behavior to watch for is the Magnolia Warbler's tendency to rapidly fan its tail.

Like many warblers, Magnolia Warblers on their breeding grounds are territorial. Males form territories shortly after arrival on their breeding grounds, by singing, displaying their plumage, and chasing other males. Their aggressive displays include tail spreading to show their white tail markings, flying towards the intruder with outspread wings and tail, and chasing away competing birds. Magnolia Warblers reportedly show little fear of human observers and will tolerate a reasonable amount of contact.

Male and female Magnolia Warblers have a shared territory on their breeding grounds and maintain these territories through the nesting cycle until the young have fledged. In the post-breeding period, however, Magnolias often join mixed-species foraging flocks. Such flocks are usually led by the ubiquitous Black-capped Chickadees, whose chickadee-dee-dee calls serves as a useful marker for the possible presence of other species, including Magnolia Warblers.

Magnolia Warbler: Migration

The Magnolia Warbler is a Neotropical migrantNeotropical migrant/Neotropical migratory birds: Any species of bird whose breeding area includes the North American temperate zones and that migrates south of the continental United States during nonbreeding seasons. Neotropical migrant birds breed in North America during the spring and early summer and spend the winter in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. , meaning that it winters south of the continental United States and migrates to North American temperate zones to breed in the spring and summer. The winter range of Magnolia Warblers includes Mexico, Central America, and the West Indies.

Magnolia Warblers, like the Blackburnian Warbler and the Chestnut-sided Warbler, are trans-Gulf migrants, meaning that they migrate across the Gulf of Mexico rather than around it.

The northbound spring migration for Magnolia Warblers begins as early as March, later than early-spring migrants, such as Northern Parulas and Palm Warblers, but earlier than late migrants, such as the Mourning Warbler. Magnolia Warblers reportedly appear in the southern US in early April, with females arriving seven to ten days after the males. This is a common pattern with warblers, as well as most other migratory bird species; the males arrive early to establish their territories before their prospective mates appear.

The southbound fall migration begins in early to mid-August, with most birds generally reaching their wintering grounds in late September and early October. The fall route is more easterly than that of spring. Females and hatch-year birds leave their breeding grounds earlier than the male. Fall migration tends to be more leisurely than spring migration.

Migration patterns affecting the Magnolia Warblers we see here in the Adirondack Mountains reflect these trends.

- In the Adirondack Park, the pattern of eBird sightings from the six core Adirondack Park counties indicate that Magnolia Warblers begin arriving in early May. The number of eBird sightings peaks starting in mid-May through mid-July. Some of the birds seen during this period will probably continue north to breed in Canada, while some will remain to breed in our region.

- Magnolia Warblers apparently begin leaving their breeding grounds in the Adirondacks in August. Estimating the departure time is difficult, because of the problem of disentangling reports which reflect birds which breed in the Adirondacks and those reflecting birds which are migrating through the area from Canada. In any event, it appears that most Magnolia Warblers who breed in the Adirondacks probably begin leaving here in the first three weeks of August. By mid-October most Magnolia Warblers will have left the six core Adirondack Park counties, with a few stragglers reported in late October.

Like many other warblers, Magnolia Warblers are usually nocturnal migrants. They generally depart at night, although they may also make correction flights in the early morning to adjust their route if displaced by winds during the previous night. Magnolia Warblers migrate in loose aggregations and join mixed flocks during the day to forage and refuel for the next night's flight. During migration, Magnolia Warblers are found in low trees and shrubs at forest edges, wood lots, and parks.

Magnolia Warbler: Diet and Foraging

As with other New World Warblers, Magnolia Warblers feed primarily on insects on their breeding grounds. Caterpillars, especially spruce budworm when abundant, represent a main item on the menu. Magnolia Warblers also eat weevils, leaf beetles, leafhoppers, aphids, and spiders.

Like other warblers, Magnolia Warblers are active foragers, in constant motion while pursuing their prey.

- Magnolia Warblers forage in both conifers and broad-leaved vegetation, often finding their prey on small live twigs or dead branches or searching the undersides of needles and leaves for their insect prey. They also do some hover gleaningHover gleaning: A foraging strategy in which prey is gleaned from a surface while the foraging bird is airborne. (hovering to search for prey on the vegetation surface) and sallyingSallying: A foraging strategy in which the bird catches its insect prey in the air, but returns to a perch to consume it. (catching insects in the air, rather than on foliage.).

- Magnolia Warblers forage mainly on low and mid-level vegetation. This pattern contrasts with that of Blackburnian Warblers and Cape May Warblers, which forage high in the treetops, as well as species that forage on the forest floor, such as Northern Waterthrush or Hermit Thrush,

Male and female Magnolia Warblers use different substrates. A 1968 study of foraging by spruce-wood warblers in Maine found that male Magnolia Warblers (like the Yellow-rumped Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, and Blackburnian Warbler) foraged at higher levels than their female counterparts. While males foraged nearer to the height of their singing perches, females foraged at lower heights, closer to their nesting areas.

During migration, Magnolia Warblers supplement their diet with fruit. Their winter diet is said to include both fruit and nectar.

Magnolia Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

The breeding cycle for Magnolia Warblers begins when the males (who arrive up to a week or more before their female counterparts) establish territories, a process that sometimes involves fierce fights between rival males. Pair formation occurs soon after the female's arrival. Magnolia Warblers pairs reportedly remain together throughout the nesting season.

Nest building begins soon after pairing, about two weeks after the males have arrived. Most observers agree that both members of the pair are involved in constructing the nest, although most of the work reportedly is done by the female. Magnolias almost always place their nests in dense conifers, such as Red Spruce, Balsam Fir, and Eastern Hemlock.

The Magnolia Warbler's nest is placed close to the tree trunk and relatively low to the ground, usually between five and ten feet above the forest floor. Nests are usually well-concealed in dense vegetation. This choice of nest site contrasts with the usual nesting sites of the Blackburnian Warblers and Cape May Warblers, which place their nests in trees twenty or more feet from the forest floor. Most observers give the Magnolia Warbler a low grade in nest construction. The typical Magnolia nest is described as a flimsy, sloppy cup of grasses, weeds, and twigs.

The female Magnolia Warbler usually lays a clutch of four eggs, with the young hatching after 11-13 days. Only the female incubates. Both parents feed the nestlings. Magnolia Warblers are said to rear one and (more rarely two) broods per season. The young leave the nest at eight to ten days, but may be fed by the parents for up to 25 more days.

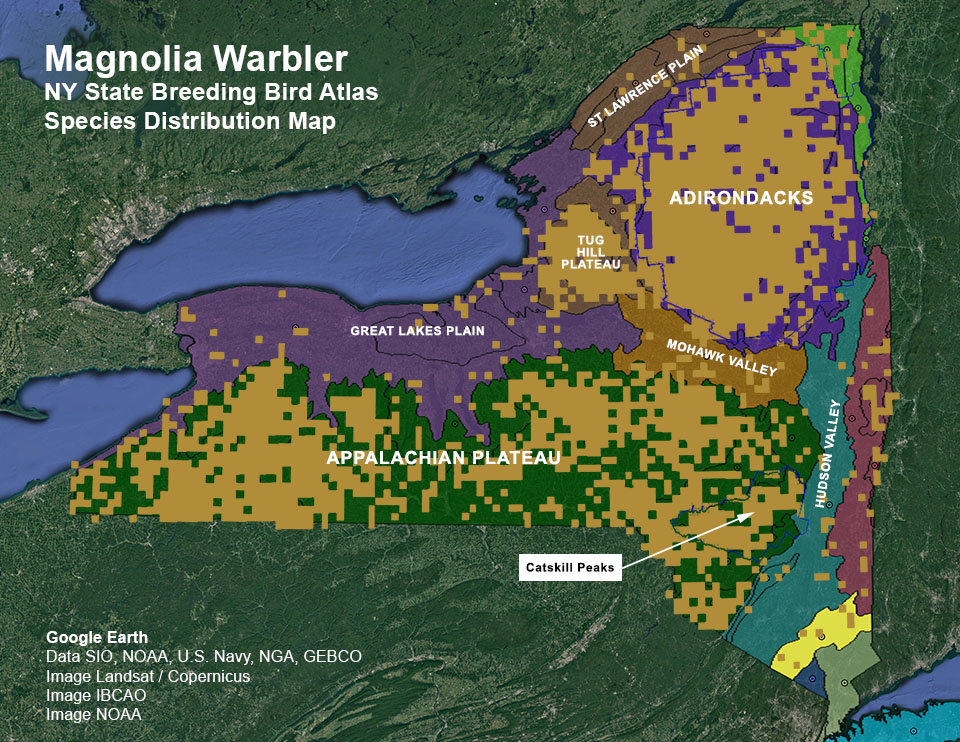

Distribution of the Magnolia Warbler

Magnolia Warblers breed in Canada and the northeastern US. In Canada, where most breeding Magnolia Warblers are found, their breeding range extends from northeastern British Columbia and southeastern Yukon eastward across the central Prairie Provinces, Ontario, southern Quebec, and southwestern Newfoundland. In the US, Magnolia Warblers breed in the northern Great Lake states, New England, parts of New York and Pennsylvania, and the Appalachians south to Virginia.

In New York State, Magnolia Warblers breed mainly in the Adirondacks, Tug Hill area, and Appalachian Plateau. This species is a common summer resident throughout the Adirondacks.

- In the 1980-1985 New York State Breeding Bird survey, breeding Magnolia Warblers were common in most of the Adirondacks at elevations below 4,000 feet. Blocks with breeding Magnolias were also found in the Tug Hill Plateau, the Appalachian Plateau at elevations above 1,000 feet, and in the Rensselaer Hills (in eastern New York State, between Albany and the Massachusetts and Vermont borders).

- The 2000-2005 New York State Breeding Bird Survey documented a 26% increase in the number of blocks with breeding Magnolia Warblers. The regional distribution of Magnolia Warblers did not change significantly, with breeding Magnolias present in most blocks within the Adirondack Park and the Tug Hill Plateau. Substantial increases were found in the number of blocks with breeding birds in both the eastern and western portions of the Appalachian Plateau.

- Preliminary findings from the third New York Breeding Bird Atlas, which began on 1 January 2020 and covers 2020-2024, are consistent with this pattern. Most of the confirmed breeding sites are in the Adirondacks, with a few others scattered in the Appalachian Plateau.

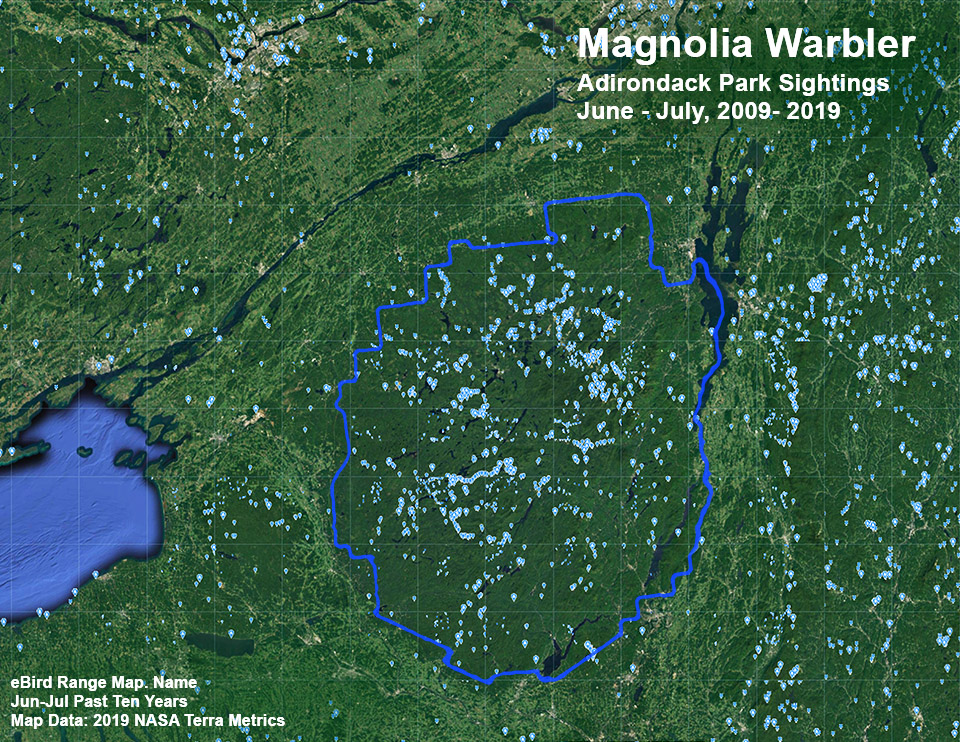

The pattern of eBird sightings for this species during the breeding season is roughly consistent with the findings of the three New York State Breeding Bird Surveys. Magnolia Warbler sightings are more numerous outside the Park during spring and fall migration seasons (with clusters of sightings south of the Finger Lakes area and on the southern shores of Lake Ontario). However, during the June-July breeding season the pattern shifts, with sightings clustered in the Adirondacks, Catskills, Tug Hill area, and Appalachian Plateau.

The Magnolia Warbler is of low conservation concern. According to Partners in Flight, the overall population of this species increased by 51% between 1970 and 2014. Partners in Flight estimated a total population of 39 million individuals, including 37 million in Canada. The population estimate for New York State was 190,000. The 2000 Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for the Adirondack Mountains indicated that populations of the Magnolia Warbler in the Adirondack Park increased by about 2% per year from 1966 to 1996.

Causes of mortality for individual Magnolia Warblers are unclear. The oldest Magnolia Warbler on record is a 8-year-old female banded and released in Ontario. Average life span is probably much shorter.

- Nestlings may die of exposure or starvation during cold, rainy periods.

- Another major cause of Magnolia Warbler mortality is predation. Potential predators include Sharp-shinned Hawks (preying on both adults and nestlings) and Red Squirrels (preying on nestlings). Possible nest predators include Blue Jays and American Crows.

- Magnolia Warblers throughout their migratory range are fairly common victims of collisions with TV towers, lighted buildings, and wires.

Magnolia Warbler: Breeding Habitat

The Magnolia Warbler is characteristically associated with dense stands of young conifers, especially spruce. Throughout its range, this species breeds in both conifer and mixed forests. It favors small, close-growing young conifers (such as Red Spruce and Balsam Fir) in either pure stands or mixed with hardwoods. Magnolia Warblers are most abundant in young, second-growth spruces, where they reportedly are the dominant species. However, Magnolias will also breed in mature forest as long as there is a dense understory.

In New York State, breeding Magnolia Warblers are generally found in high elevation forests, but can be seen as low as 1,100-1,200 feet in suitable habitat. In the Adirondacks, Magnolia Warblers are more abundant in spruce-fir-northern hardwood forests, favoring second-growth conifer and mixed forests rather than mature forests. In the Tug Hill area, Magnolias appear to prefer hemlock-northern hardwood forests, while Magnolia Warblers that breed in the Appalachian Plateau are generally seen in state forests dominated by Norway Spruce and Red Pine.

Where to find Magnolia Warblers in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Magnolia Warblers

- High Peaks

- Riverside Drive

- Lyon Mountain

- Tahawas

- Northern Region

- Bog River & Lows Lake

- Massawepie Mire

- Jones & Osgood Ponds

- West-Central Region

- Moose River Plains

- Third Lake Creek

- South Inlet

- Ferd's Bog

- Wheeler Pond Loop

- Stillwater Reservoir

- Beaver Lake

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack birders in search of Magnolia Warblers have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the west-central region of the Adirondack Park, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide. Their list of birding sites for Magnolia Warblers includes the Moose River Plains; Ferd's Bog, and the Wheeler Pond Loop in Hamilton County; Riverside Drive in Essex County; Massawepie Mire in St. Lawrence County, and Lyon Mountain in Clinton County.

The pattern of eBird sightings for the Magnolia Warbler during breeding season is roughly consistent with the Peterson/Lee recommendations and the findings of the two New York State Breeding Bird Surveys. Consistent with the findings of the two breeding bird surveys, sightings of the Magnolia Warbler during the breeding season reported through eBird are more numerous inside the Blue Line, despite the fact that there are more eBirders outside the Park.

Within the Adirondack Park, the list of eBird reports for the Magnolia Warbler includes clusters of sightings in popular birding sites, such as the Paul Smith's College VIC, Bloomingdale Bog (North and South Entrances), Blue Mountain Road, and Madawaska Pond in Franklin County; Sabattis Road, Sabattis Bog, Northville-Placid Trail (Long Lake South), Ferds Bog, Blue Mountain Trail, and Moose River Plains in Hamilton County; Cranberry Lake Biological Station and Massawepie Mire in St. Lawrence County; Roosevelt Truck Trail (South), Adirondack Interpretive Center, and Whiteface Mountain Memorial Highway in Essex County; Silver Lake Bog Preserve in Clinton County; and Amy's Park in Warren County.

Among the trails covered here, the most likely locations to look for Magnolia Warblers include John Brown Farm, any of the trails at the Paul Smith's College VIC that go through conifer or mixed forest, as well as Hulls Falls Road, the Lake Colby Railroad Tracks, and the Bloomingdale Bog Trail.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Setophaga. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of the World. Subscription Web Site. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Warren, Hamilton, Essex, Herkimer, Clinton, Franklin). Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton). Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Essex). Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton, Essex). Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Fulton, Hamilton, Herkimer, Lewis, Oneida, Saratoga, St. Lawrence, Warren, Washington counties). Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Species Maps. Magnolia Warbler. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

Kevin McGowan. Magnolia Warbler. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Bird Academy. Be a Better Birder: Warbler Identification. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Xeno-canto Database. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

G.A. Gough, J.R. Sauer, and M. Iliff. Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter. 1998. Version 97.1. Magnolia warbler. Dendroica magnolia. Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

USGS. Longevity Records of North American Birds. Magnolia Warbler. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Magnolia Warbler. Dendroica magnolia. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map (Google Earth). Magnolia Warbler. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 1980-1985. Release 1.0. Updated 6 June 2007. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Magnolia Warbler. Dendroica magnolia. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 2000-2005. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Magnolia Warbler. Dendroica magnolia. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

Kevin J. McGowan, "Magnolia Warbler. Dendroica magnolia," in Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 484-485.

Stephen W. Eaton, "Magnolia Warbler. Dendroica magnolia," in Robert F. Andrle and Janet R. Carroll (Eds.) The Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 1988). pp. 372-373.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Breeding Guideline Bar Chart. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Breeding Season Table from Atlas 2000. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Hints on Haunts. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Species Map. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 35.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), p. 98.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), p. 173, Plate 33.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 70-72, 88-90, 95-97, 105-107, 126-128, 140-144, 150-154, 161—162, 166-168, 172-174, 178-180, 211.

J. R. Sauer, D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. Trend Estimates for Core Survey Data. 1966 - 2017. Version 5.03.2019. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Trend Estimate by Species. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

Vermont Atlas of Life. Vermont Breeding Bird Species Profiles. Magnolia Warbler. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas I. Species Maps. Magnolia Warbler. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas II (2015-2019). Magnolia Warbler. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Partners in Flight. 2019. Population Estimates Database, version 3.0. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan. 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States, pp. 111. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Partners in Flight. Bird Conservation Plan for the Adirondack Mountains, pp. 37-38. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

David Allen Sibley. Sibley Birds East. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 353.

Kimball L. Garrett and John B. Dunning, Jr., "Wood-Warblers," in Christ Elphick, John B. Dunning, Jr., and David Allen Sibley (eds.), The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), pp. 492-509.

Roger Tory Peterson. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Sixth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), pp. 268-269, Map 397.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Eastern Region (Little, Brown and Company, 2013), pp. 370-371.

Richard Crossley. The Crossley ID Guide (Princeton University Press, 2011), p.410.

John Bull and John Farrand, Jr. Eds. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. Eastern Region. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p. 665, Plate 513.

Edward S. Brinkley. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), p. 385.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. Stokes Field Guide to Warblers (Little, Brown and Company, 2004), pp. 20-26, 62-63.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 340-348, 537, 542-543, 546-548.

Chris G. Earley. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 40-43. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 121-128. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Jon Curson, David Quinn and David Beadle. Warblers of the Americas. An Identification Guide (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), pp. 42-43, 118-119. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett. A Field Guide to Warblers of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), pp. 64-65, 240-248. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Douglass H. Morse. American Warblers: An Ecological and Behavioral Perspective (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 61, 63, 120-121, 174-178. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

Alexander Sprunt, Jr., "Magnolia Warbler. Dendroica magnolia," in Ludlow Griscom, Alexander Sprunt, Jr. et al., Eds. The Warblers of North America (The Devin-Adair Company, 1957), pp. 121-122, Plate 18. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

Arthur Bent. Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers. Part One and Part Two (Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 203, 1953), pp. 195-211, Plates 26-28. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

Paul Sterry. Warblers and Other Songbirds of North America: A Life-size Guide to Every Species (Harper-Collins Publishers, 2017), p. 206.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), p. 124. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Mountain Fir Forest. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Magnolia Warbler. Setophaga magnolia. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

John Eastman. The Book of Forest and Thicket: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern North America (Stackpole Books, 1992), pp. 100-104, 150-156.

Aretas A. Saunders. The Summer Birds of the Northern Adirondack Mountains. Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin. Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 326-499. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Theodore Roosevelt, "The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, N.Y.," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 501-504. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Perley M. Silloway, "Relation of Summer Birds to the Western Adirondack Forest," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 4 (March 1923), pp. 396-486. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 16-17, 22, 408-411, Plate 97. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

C. Hart Merriam, "Preliminary List of Birds Ascertained to Occur in the Adirondack Region. Northeastern New York," Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, Volume 6, Number 4 (October 1881), pp. 225-235. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

James A. Jobling. Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names (Christopher Helm, 2010), pp. 237-238. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

Floyd E. Hayes, "Definitions for Migrant Birds: What Is a Neotropical Migrant?" The Auk, Volume 112, Number 2 (April 1995), pp. 521-523. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

Irby Lovette, "Spruce-Woods Warblers Revisited: 60 Years Later, the Cast of Characters Has Changed," Living Bird (Summer 2016). Retrieved 4 February 2020.

Michale J. Glennon and Heidi E. Kretser, "Size of the ecological effect zone associated with exurban development in the Adirondack Park, NY," Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 112 (April 2013), pp. 10-17.

Douglass H. Morse, "A Quantitative Study of Foraging of Male and Female Spruce-Woods Warblers," Ecology, Volume 49, Number 4 (July 1968), pp. 779-784. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

William Brewster, "The Black-And-Yellow Warbler (Dendrœca maculosa)," Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, Volume 2, Number 1 (January 1877), pp. 1-7. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Hanna Kokko, Tómas G. Gunnarsson, Lesley J. Morrell, and Jennifer A. Gill, "Why Do Female Migratory Birds Arrive Later Than Males?" Journal of Animal Ecology, Volume 75, Issue 6 (2006), pp. 1293–1303. Retrieved 19 February 2020.