Birds of the Adirondacks:

Palm Warbler (Setophaga palmarum)

The Palm Warbler (Setophaga palmarum) is a rusty-capped, yellow and brown warbler that breeds in bogs in Canada and the Adirondacks of upstate New York and winters primarily in the southeastern and Gulf Coast regions of the United States and the Caribbean.

The Palm Warbler is a member of the New World Warbler or Wood Warbler family (Parulidae). It is one of at least 33 species that make up the Setophaga genus. This group of warblers includes other species, such as the Blackburnian Warbler and Cape May Warbler, which breed in the Adirondack Mountains and other northern habitats in spring and summer and migrate south to warmer areas in the winter.

- The Palm Warbler derives its name from Johan Friedrich Gmelin, a German naturalist who named the bird based on a specimen collected on Hispaniola, an island in the Caribbean which has palm trees.

- Folk names for the Palm Warbler include Red-poll Warbler, Yellow Palm Warbler, Yellow Redpoll Warbler, Yellow Red-poll Warbler, Wagtail Warbler, and Tip-up Warbler. The latter two names are a reference to the bird's constant tail pumping.

Palm Warbler: Identification

The Palm Warbler is a brownish bird with a brownish-olive back, variable yellow below, brown to rufous streaking on the breast, low contrast wing bars, and a rusty cap. This bird is about 4.7 to 5.5 inches in length, with a wingspan of 7.9 to 8.3 inches. Males and females are similar.

- One diagnostic key is the chestnut or reddish streaking on the breast. Most warblers have black or gray streaking.

- Another diagnostic key is the wide, square area of black at the base of the tail.

- Palm Warblers have a bright yellow patch under the base of the tail.

- They have a wide eyebrow (above the eye), varying from whitish to bright yellow.

There are two subspecies: the Western Palm Warbler (Setophaga palmarum palmarum) and the Yellow Palm Warbler (Setophaga palmarum hypochrysea). The two subspecies have different breeding grounds, migration routes, and migration timing, but overlap on their wintering grounds.

- The Western Palm Warbler breeds from James Bay in Canada to the west and winters chiefly in the Caribbean Basin. Western Palm Warblers are somewhat drab birds with whitish bellies, a pale eyebrow, and yellow under-tails.

- The Yellow Palm Warbler breeds east of Hudson Bay, from eastern Ontario to southern Labrador and Newfoundland. It winters primarily in the Gulf region of the southeastern US. It migrates much earlier in the spring and later in the fall than the Western Palm Warbler. Yellow Palm Warblers are more colorful than their western counterparts. They have yellow bellies, a bright yellow eyebrow, yellow throat, and bright rufous streaks on their breasts.

- Fall birds of both subspecies are duller overall than spring birds. Juvenile birds are very similar to adults.

Other warblers that might be confused with the Palm Warbler include the Cape May Warbler and the Yellow-rumped Warbler.

- The Palm Warbler is somewhat similar in appearance to the adult male Cape May Warbler, which also has some rust on its face. However, the Cape May does not have rufous coloring on its crown or breast like Palm Warblers. Moreover, Cape May Warblers do not bob their tails up and down like Palm Warblers.

- Another similar species is the Yellow-rumped Warbler. Female Yellow-rumped Warblers can be brownish like the Palm Warbler. However, Palm Warblers have yellow under the tail, while Yellow-rumped Warblers have a yellow patch above the tail, with white under the tail.

Palm Warbler: Songs and Calls

The Palm Warbler has a single song, which is reportedly used for both courtship and territorial defense. It is a buzzy, flat-toned trill, consisting of 4-16 buzzy syllables which are uttered slow enough to count but fast enough to sound like a continuous trill. Each song, which lasts from one to three seconds, is interspersed with 12 to 18 seconds of silence.

Only the male Palm Warbler sings, usually from the tops of trees and shrubs, with the head thrown far back. Males sing frequently when they arrive on their breeding groups and continue singing into early or mid-July. They usually begin singing soon after dawn and sing until the early afternoon. The birds usually do not sing later in the day.

The Palm Warbler's trill is similar to the trill of Chipping Sparrows, but is much slower. The Palm Warbler's trill is also somewhat similar to the trill of Dark-eyed Juncos. However, Chipping Sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos are not normally found in the bog habitats frequented by Palm Warblers.

The Palm Warbler has two different kinds of calls. One is a sharp, husky "tchit." The call is said to be more metallic and sharper than the chip of a Yellow-rumped Warbler. Palm Warblers also make a louder and sharper alarm note.

Palm Warbler: Behavior

The Palm Warbler is a ground-loving species, spending much of its time on the ground. It is known for its habit of bobbing its tail up and down, both on the ground and when perched. This trait distinguishes it from several other birds of somewhat similar appearance.

The Palm Warbler's flight is slightly bouncy, with shallow, steady wing beats and little gliding. A side view of the Palm Warbler in flight shows a slender, slightly hunchbacked silhouette, with a long tail.

Palm Warbler: Migration

The Palm Warbler is a medium-distance migrant, spending its winters south of the Adirondack Park. It is a nocturnal migrant which migrates earlier in the spring and later in the fall than most other wood warblers. It often migrates in small flocks with other warblers and songbirds, arriving on its breeding grounds when the bogs are still frozen.

- The yellow subspecies, which breeds east of John Bay, winters mainly in the Gulf region of the Southeast and migrates up the East Coast in the spring.

- The Western Palm Warbler winters chiefly in the Caribbean Basin and migrates northward in the spring mostly west of the Appalachians.

The Palm Warbler is one of the first warblers to arrive in the Adirondacks in the spring and one of the latest to leave our region in the fall.

- Birders can start looking for the Palm Warbler on Adirondack bogs by about mid-April.

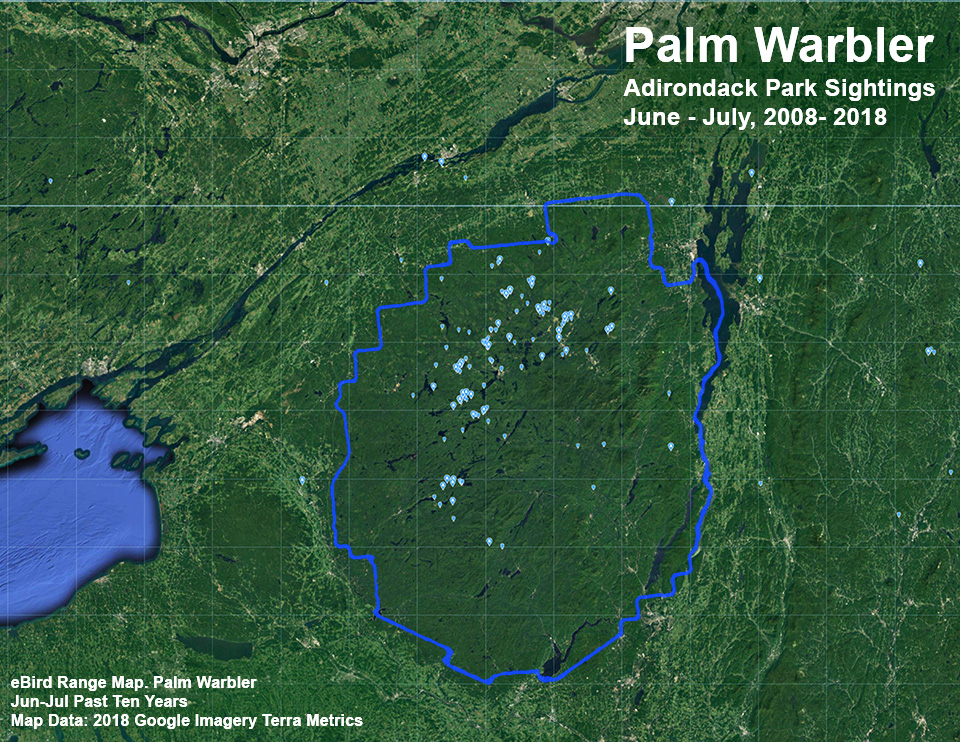

- Data from eBird species maps show many sightings in the Adirondack Park through the end of September.

- By early to mid-October, most of our Palm Warblers will have left the area for their wintering grounds to the south.

Palm Warbler: Diet and Foraging

The Palm Warbler is almost entirely insectivorous during the breeding season. It forages for its insect prey on open ground or in low vegetation. Palm Warblers also glean insects from leaves and cones, while hovering momentarily on the branches of the Black Spruce and Tamaracks that are the dominant tree species in their habitat. Palm Warblers also capture prey in the air. Their insect prey includes beetles, flies, moths, wasps, and caterpillars.

On its wintering grounds, the Palm Warbler also consumes mainly insects. However, seeds and berries (such as raspberries and bayberries) are also on the menu during this time.

Palm Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

Palm Warblers are primarily monogamous. They begin to form pairs shortly after arriving on their breeding grounds, from late April until mid-May. Nest building begins in around mid-May and is usually complete by late May or early June.

Palm Warblers build their nests on the ground in peat moss, often at the base of a small tree or shrub. Palm Warbler nests have been reported under Black Spruce, Tamarack, and various shrubs.

The cup-shaped nest is constructed out of grass, sedges, and ferns. Nest material includes Labrador Tea and the fronds of Eastern Bracken Fern. Nests may be lined with the feathers of birds such as American Bittern, Ruffed Grouse, and Blue Jay.

The female incubates the eggs, usually for about 12 days. Both parents feed the young, which leave the nest in about 8 to 12 days. In the Adirondacks, data from The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State indicate that the earliest date nestlings were observed was 2 June; the latest observation date was 24 July. The earliest date fledglings were observed was 25 June; the latest observation was 15 August.

Young Palm Warblers stay with their parents about eight days after fledging. They spend the first day or two after leaving the nest hiding in the undergrowth, since they are unable to fly for at least a day. They usually sit on branches of trees fairly close to the ground, waiting to be fed.

Information on parental care after the young birds leave the nest is sketchy. Some pairs were observed sharing feeding duties, while in one case the female assumed feeding duties until well after the young had fledged, after which the male took over.

Distribution of the Palm Warbler

Palm Warblers breed in boreal forests, with an estimated 98% breeding in Canada. The Palm Warbler's breeding range extends from the Northwest Territories to Newfoundland, southward to Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, central Ontario, southern Quebec, and Maine.

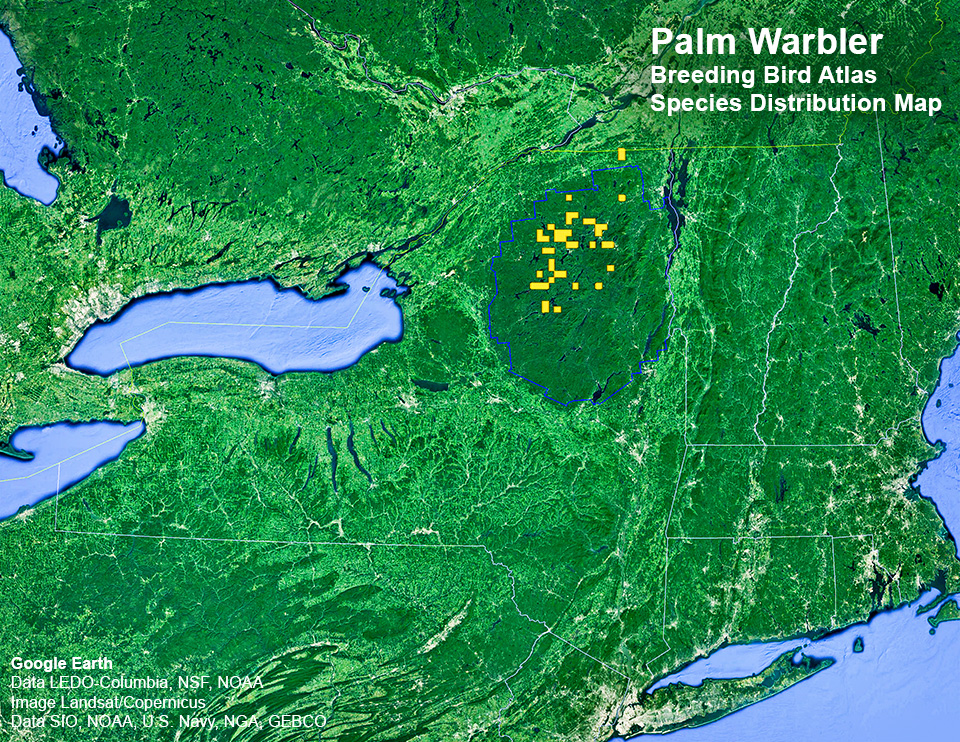

In New York State, which is south of this species' main breeding range, the Palm Warbler is commonly seen as a migrant. Its appearance in the state as a breeding bird is fairly recent. There was no record of a breeding pair in the Adirondack Park until the eighties, when New York State's first Breeding Bird Atlas began.

Species accounts for the Palm Warbler from the 1980-85 and 2000-05 Breeding Bird Surveys indicate that breeding for this species is restricted to the Adirondack Mountains. The surveys show that, within the Adirondacks, breeding Palm Warblers are most common in the central and northern Adirondacks and the western Adirondack foothills. There were no reports of breeding pairs in the southern Adirondacks or the eastern periphery of the Adirondack Park.

Palm Warbler: Habitat

Palm Warblers breed in bogs and open boreal coniferous forests with scattered evergreen trees, usually near water. Ecological communities in the Adirondacks which host Palm Warbler breeding pairs include Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog, Dwarf Shrub Bog, Spruce Flats, and Patterned Peatland.

In a Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog, for instance, the characteristic trees are Black Spruce and Tamaracks, usually stunted specimens in an open canopy stand.

- The shrub layer consists of Leatherleaf, Sheep Laurel, and Labrador Tea.

- The dominant ground cover is peat moss. Characteristic herbs include Cottongrass and Pitcher Plant.

- Characteristic birds, in addition to the Palm Warbler, include Lincoln's Sparrow, Golden-crowned Kinglet, White-throated Sparrow, and Canada Jay.

Where to find Palm Warblers in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Palm Warblers

- Northern Region

- Whitney Wilderness

- Bog River and Lows Lake

- Five Ponds Wilderness

- Massawepie Mire

- Spring Pond Bog

- Paul Smith's College VIC

- Jones & Osgood Ponds

- Bloomingdale Bog

- Eastern Region

- Crown Point

- West-Central Region

- South Inlet

- Raquette Lake Inlets

- Shallow Lake

- Ferd's Bog

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Palm Warblers are relatively common throughout New York State during the spring and fall migration. Most of the eBird sightings of Palm Warblers in the state are from April and early May, as the birds make their way through the state on their way to their northern breeding grounds, and then again in September and October, as the birds migrate south to their wintering grounds.

During the breeding season, however, Palm Warblers are largely restricted to their breeding grounds in the Adirondack Mountains. Adirondack birders have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the northern Adirondacks and west-central region, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide.

Within New York State, most of the Palm Warbler eBird sightings (consistent with the findings of the Breeding Bird Survey) are in the northern and central Adirondacks, as well as the western Adirondack foothills. Palm Warbler sightings are clustered around popular birding destinations such as Sabattis Bog in Hamilton County, Massawepie Mire in Saint Lawrence County, and the Paul Smith's College VIC and Bloomingdale Bog in Franklin County.

Among the trails covered here, the Boreal Life Trail at the Paul Smith's College VIC and the Bloomingdale Bog Trail are probably the most reliable places to find Palm Warblers.

- On the Boreal Life Trail, look for the Palm Warbler along the 1,600-foot boardwalk across Barnum Bog. Palm Warblers nest on the bog and are reliably seen here from late April through September. Although Palm Warblers spend much of their time rustling about on the ground, you are most likely to see them when they fly to the branches or tops of the stunted Tamaracks and Black Spruce that dot the bog.

- On the Bloomingdale Bog Trail, Palm Warbler sightings are clustered along the trail between the north entrance and Bigelow Road. Palm Warblers are frequently seen along this trail from late April through September.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Macaulay Library. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

Xeno-canto Database. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

eBird. Species Map. Palm Warbler. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Palm Warbler. Dendroica palmarum. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Palm Warbler. Setophaga palmarum. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map. Palm Warbler. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 502-501, 640.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 36.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), pp. 8,100.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 27-29. 92-101, 105-107, 114-116, 120-122, 126-130, 153-162.

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Verne E. Davison. Attracting Birds from the Prairies to the Atlantic (Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1967), pp. 142-143.

Margaret McKenny. Birds in the Garden and How to Attract Them (Grosset & Dunlap, 1939), p. 225.

David Allen Sibley. Sibley Birds East. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), p. 356.

David Allen Sibley. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), p. 490.

Roger Tory Peterson. Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Sixth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), pp. 274-275.

Donald and Lillian Stokes. The New Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Eastern Region (Little, Brown and Company, 2013), p. 378.

Jonathan Alderfer, Ed. Complete Birds of North America. Second Edition (National Geographic, 2014), pp. 615-616.

Richard Crossley. The Crossley ID Guide (Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 418.

American Museum of Natural History. Birds of North America. Revised Edition (Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2016), p. 595.

John Bull and John Farrand, Jr., Eds. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. Eastern Region. Second Edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), pp. 672-673.

Edward S. Brinkley. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America (Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), p. 379.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 18, 31, 33, 38, 43, 53, 94, 148, 174, 184, 224, 230, 314, 320, 374, 396-401, 404, 409, 412, 415, 458, 482, 489, 535, 538-539, 542, 547.

Chris G. Early. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 66-67.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 213-219.

Paul Sterry. Warblers and Other Songbirds of North America: A Life-size Guide to Every Species (Harper-Collins Publishers, 2017), p. 213.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 63-64, 76. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Dwarf Shrub Bog. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Patterned Peatland. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Palm Warbler. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 430-432. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

Wallace B. Grange, "Palm Warbler Summering in Northern Wisconsin," The Auk, Volume 41, Number 1 (January 1924), pp. 160-161. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

Ron Pittaway, "Subspecies of the Palm Warbler," Ontario Birds, Volume 13, Number 1 (1995), pp. 23-27. Retrieved 13 November 2018.