A Gift of Wilderness: The Adirondack Park

The Adirondack Park is the largest publicly-protected area in the contiguous United States, encompassing about six million acres.

- The Adirondack Park is a mixture of state and private land.

- The region has over 3,000 lakes, 30,000 miles of rivers and streams, 42 peaks over 4,000 feet, and a wide variety of habitats, including globally unique wetland types and old growth forests.

Although virtually no areas of the Adirondack Park have completely escaped the impact of human activities, for many people in the northeast, the Adirondack Park is the most accessible way to experience "wilderness," in the sense of exploring and enjoying a relatively unspoiled natural habitat.

The region's escape from the agricultural and urban development that largely surrounds it is due to a combination of factors.

- The harsh climate and shallow soil meant that the region was spared the influx of settlers who moved into more fertile lands in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

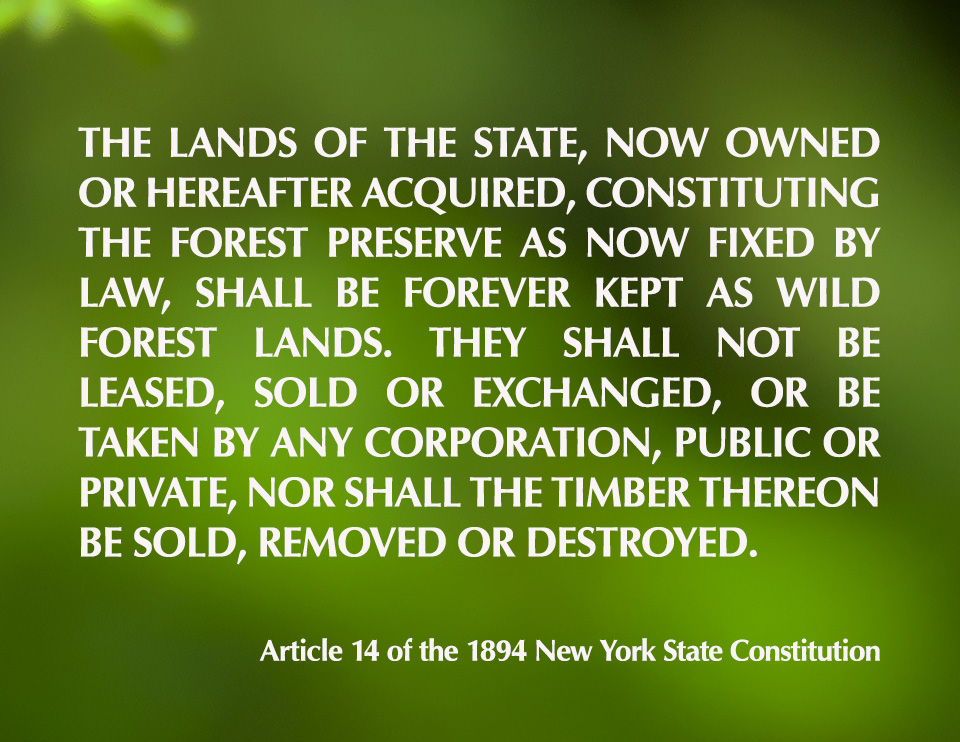

- The other major factor was the formation of the Adirondack Park in 1892 (in part a response to the ravages of the timber industry of the late 19th century), together with the adoption in 1894 of a proviso in the New York State Constitution that the Forest Preserve lands "shall be forever kept as wild forest lands."

Salvaging a Ravaged Landscape: The Creation of the Adirondack Park

There were two main factors driving the decision to preserve the Adirondack forest: the spiritual position that experiencing untrammeled nature in the wild Adirondack Mountains was restorative and the utilitarian position that maintaining healthy Adirondack forests was vital to transportation and agriculture in the rest of the state.

- The image of the Adirondacks as a refuge in a rapidly urbanizing and industrializing world was created in large part by 19th century writers promoting the region as a scenic retreat with spiritual and medical benefits – a retreat deserving of protection from the timbering interests. One example is William Murray, whose 1869 book Adventures in the Wilderness popularized the region as a place to experience "Nature in her wildest and grandest aspects."

- A second group of preservationists was lobbying to save the Adirondack forests for economic reasons. The most notable of these was Verplanck Colvin, who argued that the "chopping and burning off of vast tracts of forests in the wilderness" presented a danger to the downstate water supply. He argued that "the interests of commerce and navigation demand that the forests should be preserved; and for posterity should be set aside, this Adirondack region, as a park for New York, as is the Yosemite for California and the Pacific State."

Responding to these forces, the state government in Albany moved hesitantly toward preserving what was now seen as an increasingly endangered resource:

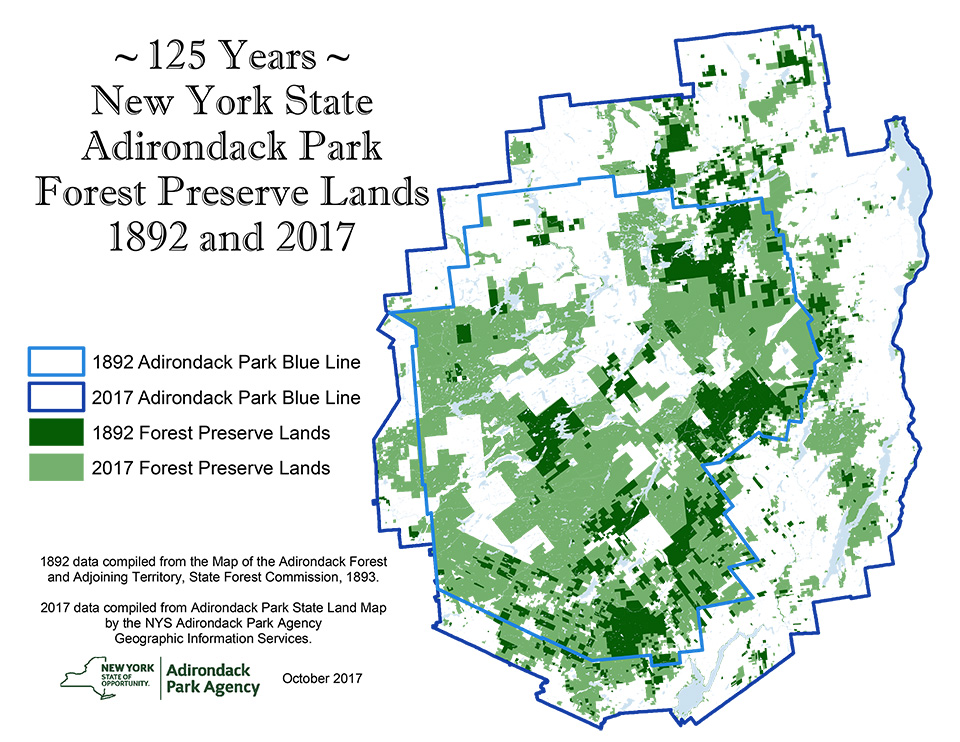

- In 1885, the Governor signed a law establishing a state Forest Preserve consisting of state lands in the Adirondacks and Catskills, which were to be "forever kept as wild forest lands." The law also set up a largely toothless three-member Forest Commission to provide administrative oversight. In its report to the legislature for 1890, the Forest Commission discussed the possibility of creating an Adirondack Park, whose boundary was delineated in blue on the map.

- In 1892, efforts to create an Adirondack Park finally succeeded with the adoption of the Adirondack Park Enabling Act. The Park consisted of all state lands inside the Blue Line. There was no mention of private lands, which comprised the majority of the area within the Blue Line.

- In 1894, a convention called to revise New York State's Constitution (primarily with regard to issues relating to the judiciary) unexpectedly endorsed an amendment that subsequently became the "Forever Wild" article. The primary impetus for the amendment was to protect downstate water supplies. The amendment was approved by New York voters that November and went into effect on 1 January 1895.

The events in Albany did not, of course, resolve the inherent conflict between public and private land and between competing claims on the land. Although the original Park law was modified in 1912 to specify that private lands within the Blue Line were statutorily considered part of the Park, it did not address how the Adirondack forests were to be protected on the many different types of private lands within the Blue Line.

Responding to New Threats to the Mountains: The Creation of the APA

Residential development within the Blue Line accelerated after World War I, as developers capitalized on the profits offered by selling small lots to middle class families in search of their own little wilderness Meccas. Over the next several decades, modest camps sprouted along hundreds of miles of previously undeveloped shorelines in the Adirondacks. The opening of the Adirondack Northway in 1967 promised to exacerbate the situation.

This unregulated development spurred action in Albany.

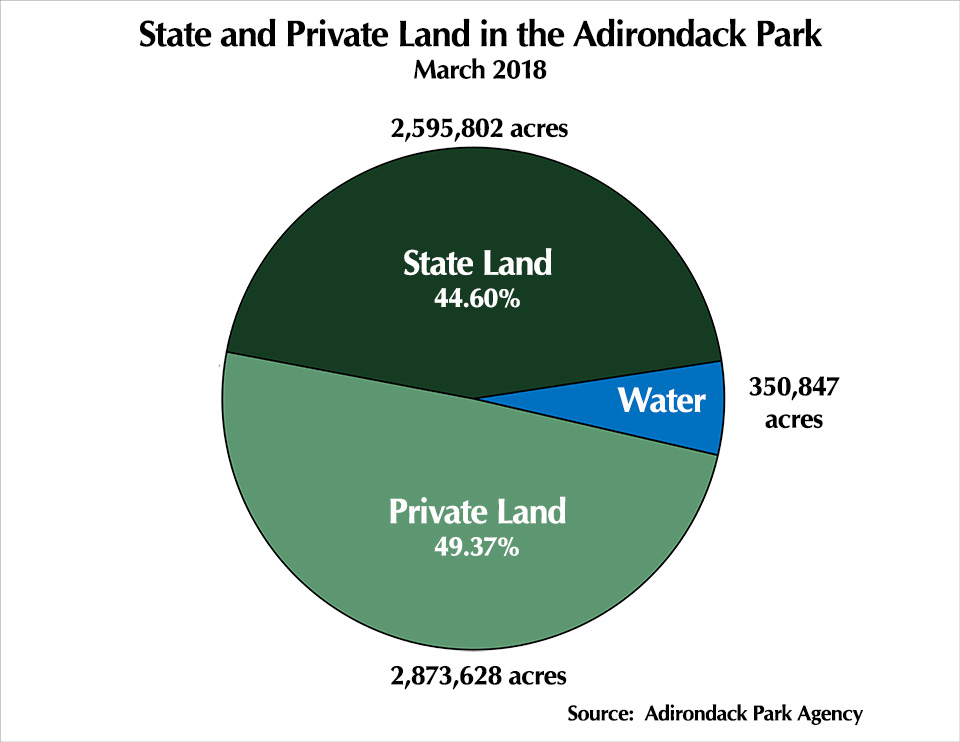

- In 1967, Lawrence Rockefeller, brother of the then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller, produced a report noting correctly that the Adirondack Park was "largely a fiction," with only 40% of the land in the Blue Line in state hands. The report recommended creation of a an Adirondack Mountains National Park of 1.7 million acres in the High Peaks area – a plan that would involve state purchase (presumably forced, in most cases) of most of the 600,000 acres then in private hands. The report, which was opposed by virtually all sides in the ongoing tussle over the future of the land within the Blue Line, proved to be a catalyst.

- Governor Nelson, exploiting the interest sparked by opposition to his brother's proposal, set up a Temporary Commission on the Future of the Adirondacks, tasked with examining the threats to the integrity of the northern forests. The result, in 1971, was the creation of the Adirondack Park Agency.

The purpose of the Adirondack Park Agency Act was to: "insure optimum overall conservation, protection, preservation, development and use of the unique scenic, aesthetic, wildlife, recreational, open space, historic, ecological and natural resources of the Adirondack park." The APA's first task was to develop long-range land use plans for both public and private lands within the boundary of the Park.

- The State Land Master Plan was adopted by the Agency and first signed by the Governor in 1972.

- In 1973, the New York legislature adopted into law the Adirondack Park Land Use and Development Plan, covering the Park's private Lands.

If the best measure of an organization tasked with balancing and adjudicating competing interests is its ability to antagonize all sides in the struggle, the APA has been a resounding success. Its actions have pleased neither conservationists who bemoan its inadequate protection of the Adirondacks' natural resources nor business interests and those locals who resent the APA's efforts to restrict their activities. The Adirondacks, however, would be a very different place today absent the political intervention from Albany that produced the Adirondack Park and the APA.

The Adirondack Park: A Patchwork of Public and Private Lands

The Adirondack Park remains an uneasy patchwork of state-owned and privately-held land.

- Private land use is regulated, with limits on buildings, roads, and clearings. There are 2.9 million acres of private land (nearly 50% of park-wide acreage), classified into six different categories: Hamlet, Moderate Intensity, Low Intensity, Rural Use, Resource Management, and Industrial Use. Permitted uses and residential density vary. For instance, there are no limits on the number of buildings and lot sizes on land classified as Hamlet. By contrast, on land classified as Resource Management, there is a limit of 15 buildings per square mile, with an average lot size of 42.7 acres. Most development on Resource Management land requires an APA permit. The limits are designed to ensure the Park will retain its natural, open space character.

- The Blue Line also encompasses 2.6 million acres of New York State land, divided into seven classifications: Wilderness, Primitive, Canoe, Wild Forest, Intensive Use, Historic, and State Administrative. The most restrictive category is Wilderness, defined as an area "where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man—where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." The Wild Forest category is less restrictive, an area which retains "an essentially wild character" while lacking "the sense of remoteness of wilderness, primitive or canoe areas."

It will come as no surprise that these categories – and the way they have been interpreted by the APA over the past forty plus years – are at the center of many of the ongoing controversies about how to preserve the wilderness aspects of the Park, while accommodating the many competing interests represented by environmentalists, property owners, developers, hunters, hikers, cyclists, snowmobilers, locals, second home owners, and the many other constituencies whose different and mutually incompatible views of the Park and its future enliven virtually ever issue affecting the Adirondacks.

References

Philip G. Terrie. Contested Terrain : A New History of Nature and People in the Adirondacks (Adirondack Museum, 1999).

Barbara McMartin. Perspectives on the Adirondacks: A Thirty-Year Struggle by People Protecting their Treasure (Syracuse University, 2002).

Phillip G. Terrie, "Cultural History of the Adirondack Park. From Conservation to Environmentalism," William F. Porter et al. The Great Experiment in Conservation. Voices from the Adirondack Park (Syracuse University Press, 2009), pp. 206 – 226.

William F. Porter and Ross S. Whaley, "Public and Private Land-Use Regulation of the Adirondack Park," William F. Porter et al. The Great Experiment in Conservation. Voices from the Adirondack Park (Syracuse University Press, 2009), pp. 227– 242.

Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park. A Political History (Alfred A. Knopf, 1978).

Paul Schneider. The Adirondacks. A History of America's First Wilderness (Henry Holt and Company, 1997).

William H.H. Murray. Adventures in the Wilderness. Camp-life in the Adirondacks (De Wolfe, Fiske & Co., 1869). Retrieved 11 January 2017.

Verplanck Colvin. Ascent and barometrical measurement of mount Seward. (The Argue Company Printers, 1872), pp. 11-12. Retrieved 11 January 2017.A Report on A Proposed Adirondack Mountains National Park. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

Adirondack Park Agency Act. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

State of New York. Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan. Approved November 1987. Updates to Area Descriptions and Delineations as authorized by the Agency Board, December 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2017.