Amphibians & Reptiles of the Adirondacks:

Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina)

The Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) is a large aquatic turtle with powerful jaws that lives in marshes, shallow ponds, streams, and other freshwater habitats in the Adirondack Mountains. The Snapping Turtle is New York State's official state reptile.

The Snapping Turtle is part of the order Testudines (Turtles). Snapping Turtles are members of the family Chelydridae (Snapping Turtles). This family also includes the Alligator Snapping Turtle, the largest freshwater turtle in North America, found primarily in the southeastern United States. The Snapping Turtle belongs to the Chelydra genus.

- The genus name is derived from the Greek Word "chelydra," which means "tortoise."

- The species name (serpentina) originates from the Latin word "serpentis," meaning "snake;" This is a reference to the long tail of this species.

- Other nonscientific names for the Snapping Turtle include Common Snapping Turtle, North American Snapping Turtle, Snapper, and Eastern Snapping Turtle.

Some sources list two subspecies: the Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina serpentina) and the Florida Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentinaosceola). However, these subspecies were abandoned after genetic evidence indicated that C. serpentina represented a single lineage. The two subspecies are not recognized by either the Integrated Taxonomic Information System or the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

Snapping Turtle: Identification

Snapping Turtles have massive heads and powerful jaws. The turtle has a short, pointed snout and a long, warty neck. Its carapaceCarapace: The dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods (such as crustaceans and arachnids) and vertebrates (such as turtles and tortoises). In turtles and tortoises, the underside of the shell is called the plastro (upper shell) is tan or olive to black and is often covered in algae. The back edge of the upper shell is serrated. The Snapping Turtle's plastronPlastron: The lower section of the turtle's shell. The upper section is called the carapace. (bottom shell) is smaller than that of most other turtles. The bottom shell is cross-shaped, yellow to tan, and unpatterned.

The Snapping Turtle's tail is thick and quite long, usually as long as the upper shell. The tail has a series of triangular spikes along the top, which develop with age. The legs are large and powerful; the webbed feet are equipped with thick, strong claws.

The Snapping Turtle is the largest species of turtle in the northeastern US. Its shell length is 8 to 20 inches in length, with most individuals weighing in between 8 and 35 pounds. Males are larger than females.

Similar Species: Wood Turtles, which also are found in the Adirondack Park, have long tails, like the Snapping Turtle. However, Wood Turtles are much smaller than snappers, and their tails are smooth.

Another Adirondack turtle – the Eastern Musk Turtle – has a relatively small bottom shell, like the Snapping Turtle. Like the Snapping Turtle, it has a rather feisty disposition. However, its tail is short, and its upper shell is highly domed.

Snapping Turtle: Behavior

Snapping Turtles are notorious for their pugnacious behavior out of water. When in the water, they tend to be shy and retiring. They are sometimes seen lying in shallow water or floating near the surface, quickly submerging if they sense danger. Snapping Turtles encountered on land, however, are very aggressive. If molested, they will lunge forward and strike at the intruder, inflicting painful injuries with their powerful jaws. This instinct to strike has been observed even in small hatchlings.

Snapping Turtles reportedly spend most of their daylight hours in shallow water, buried in mud or hidden under logs. They tend to bask less than other turtles, but can occasionally be seen on sunny days on logs or banks, or perched atop rocks that provide easy access back into the water. Basking is probably more common in areas like the Adirondacks with cooler water temperatures. Snapping Turtles usually move about by creeping slowly over the water's bottom. Female Snapping Turtles are often encountered on land, when they leave the water in search of nesting locations.

Snapping Turtles spend the cold winter months by burrowing into the debris or mud in shallow water at the bottom of ponds or lakes. Some spend winter in muskrat or beaver burrows or lodges. Snapping Turtles generally enter hibernation by late October, emerging between March and May. Some individuals, however, do not hibernate, remaining active under the ice.

Snapping Turtle: Diet

Snapping Turtles are omnivores (meaning that they eat both plants and animals). Animal matter accounts for 54% of prey items and includes fish, crayfish, aquatic invertebrates, reptiles, amphibians (such as Green Frogs), mammals (such as young North American River Otters and Muskrats), birds (mainly young waterfowl, such as Mallard and American Black Duck ducklings), and fish (including suckers, bullheads, sunfish, and perch). Plant material makes up about 37% of their menu and includes mainly aquatics such as algae and the foliage or stems of waterweed, pondweeds, and waterlilies (such as White Water Lily and Yellow Pond Lily).

The Snapping Turtle's menu reportedly varies with the seasons and the age of the turtle. In early spring, aquatic vegetation in lakes and ponds is limited, so snappers rely primarily on animal matter. As aquatic vegetation becomes more abundant, the turtles shift toward a more plant-based diet. Young Snapping Turtles are said to be more carnivorous than older specimens.

Snapping Turtles reportedly forage during both the day and night. They hunt by prowling slowly along the lake or pond water, or by lying the shallows to wait for unsuspecting prey. They will eat anything they can subdue.

Snapping Turtle: Reproduction

Throughout their range, Snapping Turtles mate from April to November. In New York State, the peak nesting period generally occurs in June. Older females reportedly nest earlier than smaller, younger ones. Female Snapping Turtles leave the water in search of a nest site, typically a sparsely vegetated site with sandy or loamy soils. Open, sunny locations are preferred. The nest site is usually located near water, but some individual Snapping Turtles may travel half a mile or more to find a suitable site, in some cases starting and abandoning several holes before completing a nest.

The turtle constructs her nest by digging with her hind feet. The nest consists of a single bowl shaped cavity, four to nine inches deep.

The female then deposits a clutch of 25 to 50 eggs in the newly-dug nest. The eggs, which are laid at intervals of one to three minutes, are white and spherical, about 1 to 1.4 inches in diameter, with a tough, leathery shell. After completing the clutch, the female refills the cavity and lumbers back to the water, leaving the eggs to incubate from the natural heat of the environment

Incubation takes three or four months, depending on the weather and climate, with longer incubation periods in more northerly areas. Incubation temperatures influences the sex of the hatchlings, with higher nest temperatures producing predominately females and lower nest temperatures producing predominantly males.

Nest predation is high. The vast majority of eggs are destroyed by predators, such as skunks, Raccoons, foxes, and coyotes. A 1980 study of Snapping Turtle nesting in northern New York found that predators destroyed 94% of the nests under study; 80% of those nests were plundered by Raccoons. Most studies have found that nest predation occurs the day or two after nesting, although a 2014 study of predation in Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario found predation occurring throughout the incubation period. Predators apparently use both visual and olfactory clues to locate nests.

Snapping Turtle hatchlings generally emerge from the nest from mid-August to early November. The hatchlings leave the nest ten to fifteen days after hatching and head for the nearest body of water. At this time, the young Snapping Turtles are vulnerable to both predation and desiccation.

In northern regions, hatchlings may overwinter in the nest, emerging the following spring. However, some of those that overwinter in the nest may freeze to death during colder winters.

Snapping Turtle: Distribution

The Snapping Turtle is widely distributed across the eastern two-thirds of the North American continent. Its range covers elevations from sea level to 2,000 meters and includes nearly all of the US east of the Rocky Mountains, ranging from Nova Scotia west to southern Alberta, south to New Mexico, and east to the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts.

The Snapping Turtle is listed by the IUCN as a species of least concern; its population is considered to be stable. It is distributed across a variety of habitats. Although Snapping Turtle populations have been intensively trapped in some regions in previous years, the species is now subject to a variety of state legislation and management efforts in both the US and Canada. In the US, for instance, trade in Snapping Turtles is restricted to animals over four inches, reducing the pet trade.

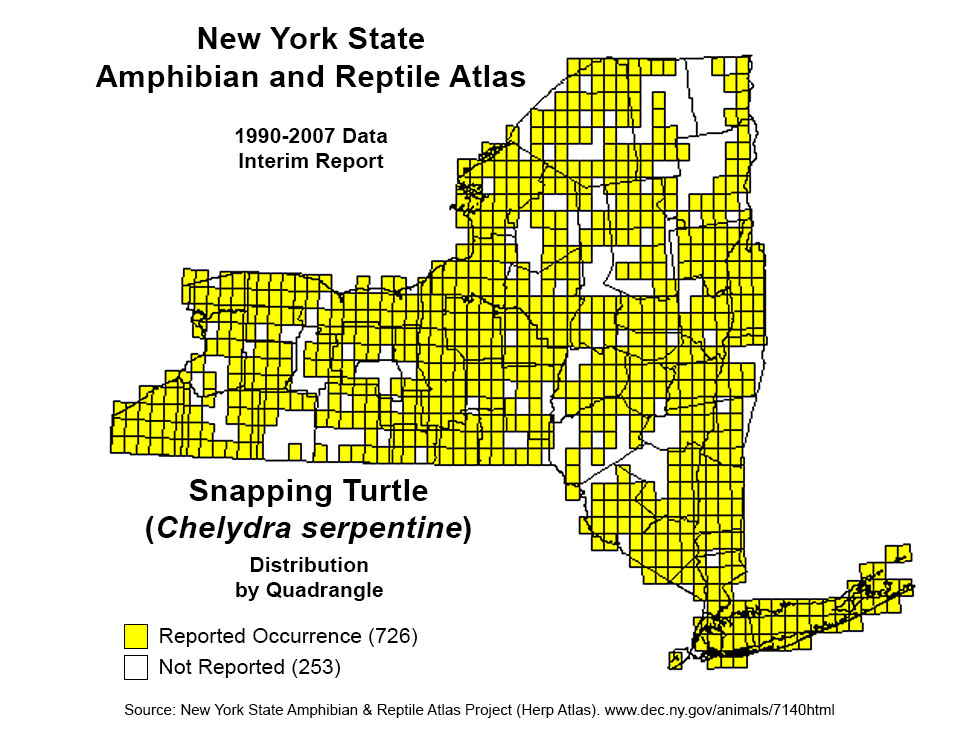

In New York State, Snapping Turtles are abundant and widespread throughout the state. Data from the New York Herp Atlas Project indicate that this species has been reported in all counties in the state, including all 12 counties with territory that falls within the Adirondack Park Blue Line.

The pattern of iNaturalist observations within the Adirondack Park is generally consistent with the distribution map in the New York State Herp Atlas.

- Snapping Turtles represent 163 out of the 307 research-grade observations of turtles and tortoises within the Blue Line.

- The Snapping Turtle is the most commonly observed turtle in the Park (followed by the Painted Turtle with 118 research-grade observations). This may be partly due to the size and distinctive appearance of Snapping Turtles. It may also reflect the greater visibility of Snapping Turtles when they leave the water in search of a nest site.

- The geographical pattern of iNaturalist Snapping Turtle observations is also consistent with the Herp Atlas, suggesting that this species is widely distributed throughout the Adirondack Park

Snapping Turtles are a long-lived species, with a lifespan of about thirty to forty years or more. Snapping Turtles are most vulnerable to predation during the nesting period. Raccoons are the major threat to both nests and hatchlings. Snapping Turtle eggs and hatchlings also fall prey to American Mink, skunks, foxes, herons, bitterns, owls, and American Crows. Adult Snapping Turtles have few natural enemies, although they may fall prey to North American River Otters. Automobile strikes represent a major cause of mortality of adults female Snapping Turtles, who often cross roads in search of suitable nesting sites.

Snapping Turtle: Habitat

Snapping Turtles spend much of the lives in aquatic habitats, including mashes, ponds, large lakes, reservoirs, and rivers. Although they can be found in almost every kind of freshwater habitat, they prefer slow-moving water and tend to be most at home in shallow, marshy swamps with a soft mud bottom and submerged and emergent plants. They overwinter on the muddy bottoms of water bodies, usually not too far from shore. Snapping Turtles appear to be relatively tolerant of polluted waters.

Because Snapping Turtles bask less frequently than some other Adirondack species, you are most likely to encounter them in the late spring, when female Snapping Turtles leave their ponds in early morning or early evening and travel overland in search of nesting areas. Their preferred nesting locations are usually within 100 feet of water in sandy or loamy soils.

List of Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles

References

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Snapping Turtle. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project. Species of Turtles Found in New York. Common Snapping Turtle. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Nature Explorer. Snapping Turtle. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

iNaturalist. Common Snapping Turtle. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Common Snapping Turtle. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Turtles of New York. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wildlife Exposure Factors Handbook. Volume 2. Office of Research and Development. EPA/600/R-93/187 (December 1993). p. 367-379. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. SSAR North American Species Names Database. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Scientific Name. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 47-48 53-54, 70-71. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Deep Emergent Marsh. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Pine Barrens Vernal Pond. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2020. Online Conservation Guide for Vernal Pool. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

Elizabeth H. Thompson and Eric R. Sorenson. Wetland, Woodland, Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont (University Press of New England, 2000), pp. 240, 344-346. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

Virginia Herpetological Society. Snapping Turtle. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Bernard S. Martof, William M. Palmer, Joseph R. Railey, and Jack Dermid. Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas & Virginia. (University of North Carolina Press, 1980), p. 146. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

Malcolm L. Hunter Jr., John Albright, and Jane Arbuckle, Eds. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Maine. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station. Bulletin 838 (1992), pp. 73, 91, 92-96, 108. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), pp. 174-175, 195.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), pp. 278-283. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 148-152 .

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. River Otter. Lutra canadensis. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Muskrat. Ondatra zibethicus. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

James P. Gibbs, Alvin R. Breisch, Peter K. Ducey, Glenn Johnson, John L. Behler, Richard C. Bothner. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New York State. Identification, Natural History, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 38-46, 159-164, Plate 33.

Arthur C. Hulse. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Cornell University Press, 2001), p.68, 188-193. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

James H. Harding and David A Mifsud. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. Revised Edition (University of Michigan Press, 2017), pp. 173-179, 265, 281.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution (University Press of New England, 2001), pp. 46, 396-399, 423-426. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John L. Behler and F. Wayne King. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), pp. 435-436, Plates 322-324. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

Mark O'Shea and Tim Halliday. Reptiles and Amphibians (Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2001). p. 50. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Thomas F. Tyning. A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles (Little, Brown and Company, 1990), pp. 180-191. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Hobart M. Smith and Edmund D. Brodie, Jr. Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification (Western Publishing Company, Inc., 1982), pp. 38-30

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of the World. Subscription Web Site. American Black Duck, American Crow, Common Loon, Lesser Scaup, Lesser Yellowlegs, Mallard, Ring-necked Duck, Wood Duck Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Ontario Nature. Reptiles and Amphibians. Snapping Turtle. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

Carl H. Ernst and Jeffrey E. Lovich. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Second Edition. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), pp.113-137.

Carl H. Ernst and Roger William Barbour. Turtles of the World (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), pp. 130-132. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

Archie Fairly Carr. Handbook of Turtles. The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California (Comstock Pub. Associates, 1952), pp. 61-69. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

Carl H. Ernst and Roger William Barbour. Turtles of the United States (The University Press of Kentucky, 1972), pp. 19-25. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

The Reptile Database. Chelydra serpentina. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Peter J. Petokas and Maurice M. Alexander, "The Nesting of Chelydra serpentina in Northern New York," Journal of Herpetology, Volume 14, Number 3 (31 July 1980), pp. 239-244. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

Tom A. Langen, Kimberly M. Ogden and Lindsay L. Schwarting,"Predicting Hot Spots of Herpetofauna Road Mortality along Highway Networks," The Journal of Wildlife Management, Volume 73, Number 1 (January 2009), pp. 104-114. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

Daniel C. Wilhoft, Mario G. Del Baglivo, and Megan D. Del Baglivo, “Observations on Mammalian Prediation of Snapping Turtle Nests (Reptilia, Testudines, Chelydridae),” Journal of Herpetology, Volume 13, Number 4 (15 November 1979), pp. 435-438. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

Julia L. Riley and Jacqueline D. Litzgus, “Cues Used by Predators to Detect Freshwater Turtle Nests May Persist Late into Incubation,” The Canadian Field-Naturalist, Volume 128, Number 2 (2014). pp. 179-188. Retrieved 14 November 2020.