Ferns of the Adirondacks:

Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis)

Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis) is a tall, deciduous fern with fertile fronds crowned by clusters of rusty-colored spores. It grows on stream banks and in swamps, marshes, fens, and other wetlands in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York.

The Royal Fern is a member of the Osmundaceae family (Royal Fern Family). This family contains two genera:

- The Royal Fern is part of the genus Osmunda. This genus also includes the Interrupted Fern – another fern often seen in Adirondack wetlands.

- The other genus (Osmundastrum) includes the Cinnamon Fern, another fern commonly found in wetlands in the Adirondack Park.

Some recent genetic studies suggest that the Royal Fern found in North America is a separate species and should be recategorized as Osmunda spectabilis. The iNaturalist data base has adopted this change and now identifies this species as Osmunda spectabilis, with the common name American Royal Fern. However, most handbooks and data bases (including the New York Flora Atlas, Flora of North America, the Integrated Taxonomic Information System, and the US Department of Agriculture Plant Database) continue to identify Royal Ferns as Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis.

- The origin of the family name (Osmundaceae) is unclear. The most popular theory is that it was originally derived from the name Osmunder – the Saxon name for the Norse god Thor, who (according to legend) hid his family from danger in a clump of these ferns.

- The species name regalis is from the Latin, meaning "royal" or "regal." The variety name (spectabilis) is Latin for "noteworthy" or "remarkable."

The common name (Royal Fern) is apparently a reference to the "crown" of fertile leaflets which appear at the top of the fertile fronds. Other common names for this fern include Flowering Fern, American Royal Fern, Regal Fern, and King Fern.

Identification of Royal Ferns

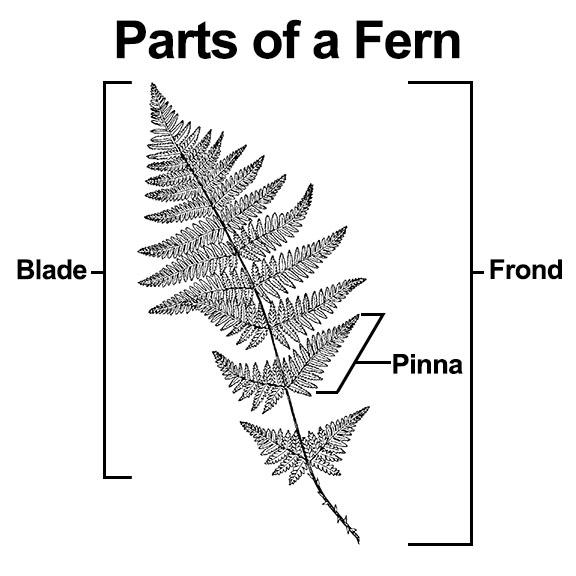

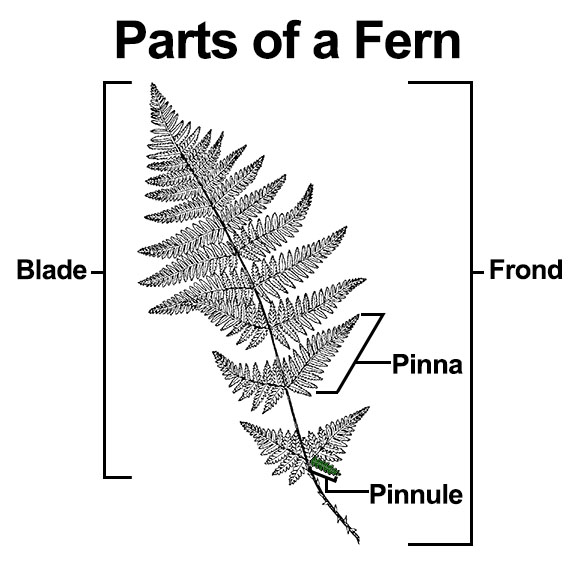

Royal Ferns are large, imposing ferns, growing erect in a cluster up to five or six feet high. Its pale green foliage is deciduous, turning varying shades of yellow, gold, brown, or russet in the fall. From a distance, Royal Ferns have a shrub-like appearance. Royal Ferns are dimorphicFrond dimorphism: Refers to a difference in ferns between the fertile and sterile fronds., meaning that the sterile fronds and fertile fronds are different in appearance.

Sterile frondsSterile frond: A frond without sporangia (spore cases). are up to 3½ feet long and 2½ feet wide.

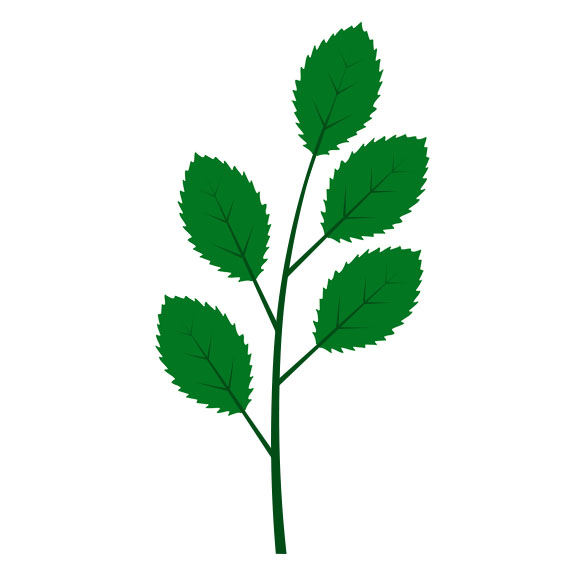

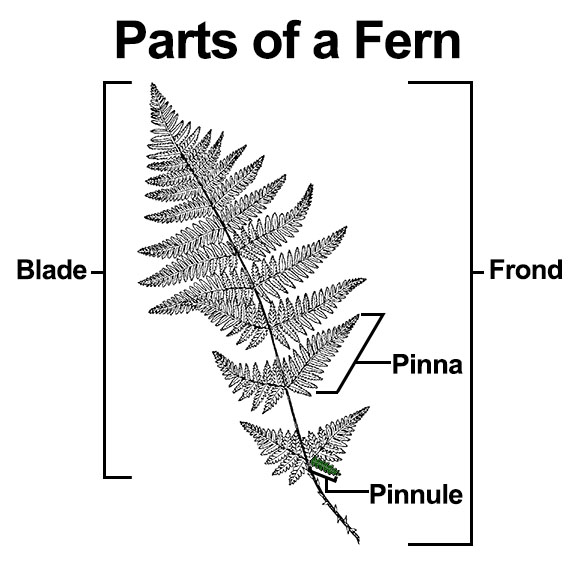

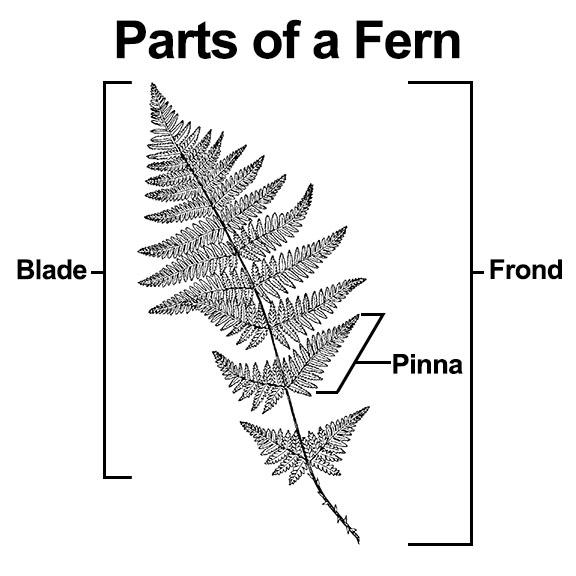

- The sterile fronds have six or more pairs of widely separated pinnae

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). (leaflets).

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). (leaflets). - Each pinna is subdivided into eight or more pairs of pinnules

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. (subleaflets).

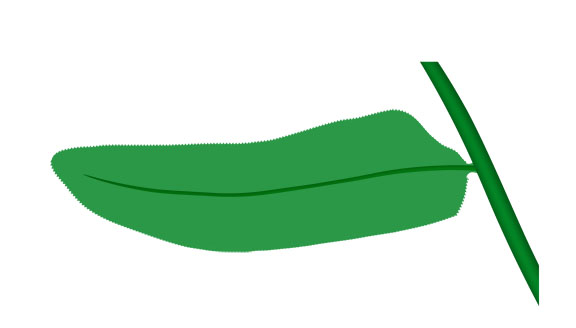

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. (subleaflets). - The pinnules are also widely separated. The pinnules are 1–2¾ inches long. They are arranged in a mostly alternate

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem. pattern, which means that they emerge from the stem separately. The pinnules are oblong and have very short stalks and minute teeth

Alternate: An arrangement of leaves (or buds) on a stem (or twig) in which the leaves emerge from the stem one at a time. This often makes the leaves appear to alternate on the stem. pattern, which means that they emerge from the stem separately. The pinnules are oblong and have very short stalks and minute teeth Minutely toothed: Refers to the margin (edge) of a pinna or pinnule which has very tiny teeth and may appear smooth., so tiny that the pinnule can appear to be smooth.

Minutely toothed: Refers to the margin (edge) of a pinna or pinnule which has very tiny teeth and may appear smooth., so tiny that the pinnule can appear to be smooth.

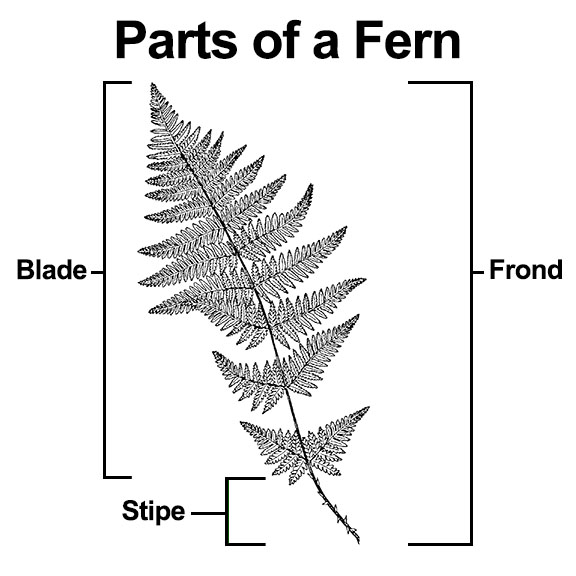

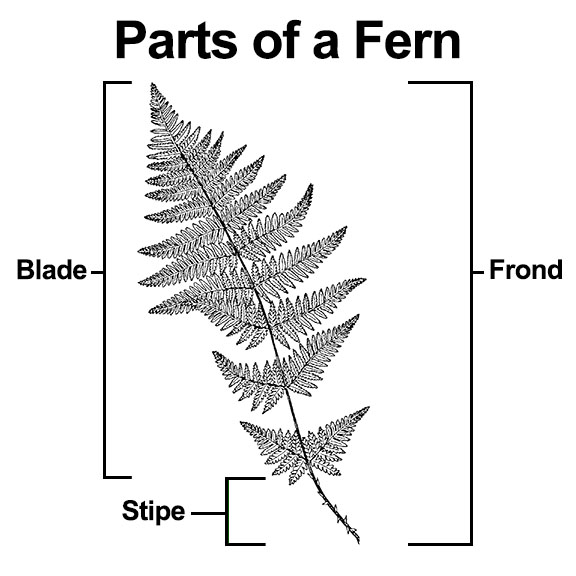

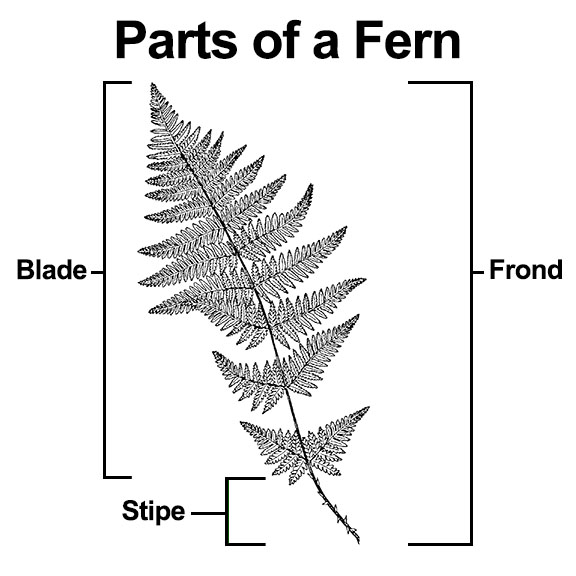

The fertile frondsFertile frond: A frond with sporangia (spore cases). of Royal Ferns are more upright. In appearance, they are similar to the sterile fronds in the lower and middle sections of the blade Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond.. However, at the top of the blade of a fertile frond, there is a distinctive cluster of smaller, branched sporangiaSporangium: Spore cases inside which the spores develop. (plural = sporangia)-bearing pinnules (subleaflets). The pinnules are green before and at maturity, turning light to dark rusty brown in color after the spores have dispersed.

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond.. However, at the top of the blade of a fertile frond, there is a distinctive cluster of smaller, branched sporangiaSporangium: Spore cases inside which the spores develop. (plural = sporangia)-bearing pinnules (subleaflets). The pinnules are green before and at maturity, turning light to dark rusty brown in color after the spores have dispersed.

Royal Ferns grow from a rhizome Rhizome: The modified subterranean stem of a plant that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks. which forms a mat, typically rising several inches above the soil surface. The dense rhizome looks like a tussock, with the remains of old stipes

Rhizome: The modified subterranean stem of a plant that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks. which forms a mat, typically rising several inches above the soil surface. The dense rhizome looks like a tussock, with the remains of old stipes Stipe: The stalk below the blade (the expanded, leafy part of the frond). (stalks).

Stipe: The stalk below the blade (the expanded, leafy part of the frond). (stalks).

The fiddleheadsFiddlehead: The unfurling young frond of true ferns, which loosely resembles the ornate, curled end of a fiddle. (Synonym=crosier) of Royal Ferns emerge in early spring and are covered with brownish hairs when young. The wine-colored fiddleheads quickly lose their covering of woolly hair and become smooth. The stems are pale pink to wine.

Clues to identifying the Royal Fern and differentiating it from other ferns include its preferred habitat and its physical characteristics.

- Royal Ferns prefer moist or wet soil, so look for it in wetland habitats, including swamps and steam banks.

- Royal Ferns are large ferns with widely spaced, minutely toothed pinnules, usually arranged alternately.

Another clue to identifying the Royal Fern is the fact that its fertile fronds are very different from its sterile fronds – a characteristic that it shares with Interrupted Ferns, Cinnamon Ferns, and Sensitive Ferns. If you find a fern with two different types of fronds growing in moist soil, it may well be one of these ferns.

- As with the Royal Fern, the fertile fronds of Cinnamon Ferns appear in the center of the sterile fronds. However, the Cinnamon Fern's fertile fronds lack the green pinnules

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. characteristic of the Royal Fern.

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. characteristic of the Royal Fern. - While the Royal Fern's fertile fronds has fertile pinnae at the end of the blade

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond., the Interrupted Fern has fronds that are "interrupted" by two to five pairs of fertile pinnae in the midsection.

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond., the Interrupted Fern has fronds that are "interrupted" by two to five pairs of fertile pinnae in the midsection. - The fertile blades of Sensitive Ferns have beadlike pinnae

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). and lack the green pinnules characteristic of the Royal Fern.

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). and lack the green pinnules characteristic of the Royal Fern.

Uses of Royal Ferns

The Royal Fern was used by a few native American groups for medicinal purposes. The Seminole, for instance, used a complex infusion of the roots for unspecified chronic conditions. The Iroquois used an infusion of the fronds as an anti-convulsive for children.

No edible uses of this fern were found. Several sources caution against ingestion of this and other ferns, especially in large quantities, since some ferns contain carcinogens, and many contain thiaminase, an enzyme that robs the body of its vitamin B complex.

Wildlife Value of Royal Ferns

Royal Ferns have minimal value as a food source for wildlife. The minute size of fern spores eliminates them as a significant food source. The Royal Fern is not evergreen, so its foliage does not provide a winter food source.

Relatively few insects feed on the Royal Fern; one exception is the Osmunda Borer Moth, which consumes its stems and rhizomes. When Royal Ferns occur in colonies, they can provide protective cover for wildlife.

Distribution of Royal Ferns

Royal Ferns are found in eastern North America, from Newfoundland south to Florida and west to eastern Texas. This fern is listed as Commercially Exploited in Florida, Threatened in Iowa, and Exploitably Vulnerable in New York State, where it is found in most counties (with the exception of several in western New York).

Royal Ferns occur in all counties within the Adirondack Park Blue Line.

Habitat of Royal Ferns

Royal Ferns are moderately shade tolerant. They can flourish in full sun to light shade. They prefer acid soil, but can also grow in rocky or gravelly soil which has some organic matter. This fern, like the Cinnamon Fern, prefers moist to very wet sites. The Royal Fern can tolerate periods of standing water.

Royal Ferns are classified as an obligate wetland plant, which means they almost always occur in wetlands. They are most commonly found in swamps, marshy areas, bogs, thickets, low-lying woods, stream banks, and lake shores. However, they are occasionally seen in drier, more upland sites.

In the Adirondack Mountains, Royal Ferns are commonly seen in a wide range of wetland ecological communities, including:

Royal Ferns can be seen on many of the trails covered here.

- There are some particularly imposing specimens growing on the ski slope on the Heart Lake Trail. You can also find this fern identified with an interpretive sign in the Fern Garden adjacent to the Nature Museum at Heart Lake.

- Look for a Royal Fern in the native plant garden by the front entrance of the main building at the Paul Smith's College VIC.

- Royal Ferns can be found on the banks of Sucker Brook on the Sucker Brook Trail at the Adirondack Interpretive Center.

List of Adirondack Ferns

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 82.

Boughton Cobb. A Field Guide to Ferns and their Related Families. Northeastern and Central North America. Second Edition (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005), pp. 170-171, 174-175.

Michael Burgess. A Field Guide to the Ferns of New England and Adjacent New York. Undated pp. 14, 100-101. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

Richard Mitchell. Atlas of New York State Ferns (New York State Museum, 1984), p.5. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Eugene C. Ogden. Field Guide to Northeastern Ferns (New York State Museum, 1981), p. 89, Plate 42, Retrieved 15 February 2017.

William J. Cody and Donald M. Britton. Ferns and Fern Allies of Canada (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1989), pp. 124-126. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

William J. Cody. Ferns of the Ottawa District (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1978), pp. 26-28. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

David B. Lellinger. A Field Manual of the Ferns & Fern Allies of the United States and Canada (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), pp. 120-121.

Anne C. Hallowell and Barbara G. Hallowell. Fern Finder. Second Edition (Nature Study Guild Publishers, 2001), p. 40.

George Henry Tilton, "The Flowering Fern Family," The Fern Lover's Companion. A Guide for the Northeastern States and Canada (Little, Brown, 1923). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

R.C. Benedict, "An Adirondack Fern List," American Fern Journal, Volume 6, Number 3, July-September 1916, pp. 81-85. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis (Willd.) A. Gray Retrieved 6 June 2021.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Royal Fern. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis L. var. spectabilis (Willd.) A. Gray. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

Flora of North America. Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis (Willdenow) A. Gray. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

NatureServe Explorer. Online Encyclopedia of Life. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis - L. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis L. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 38-39, 48-49, 50, 59, 60, 69-70, 74-75, 75-76, 87. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Inland Calcareous Lake Shore. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Medium Fen. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Northern White Cedar Swamp. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Graminoid Fen. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Hemlock-Hardwood Peat Swamp. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Shrub Fen. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Riverside Ice Meadow. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Shallow Emergent Marsh. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Online Conservation Guide for Silver Maple-Ash Swamp. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1. Updated 10.23.2006, p. 59. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis L. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

University of Wisconsin. Flora of Wisconsin. Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis (Willd.) A. Gray. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

Minnesota Wildflowers. A Field Guide to the Flora of Minnesota. Osmunda regalis. Royal Fern. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

Illinois Wildflowers. Grasses, Sedges, & Non-Flowering Plants. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis spectabilis. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis L. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Osmunda regalis. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

iNaturalist. American Royal fern. Osmunda spectabilis. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. American Royal fern. Osmunda spectabilis. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

Ellen Rathbone, "Crazy About Ferns in the Adirondacks," Adirondack Almanack, 20 January 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

Meiyin Wu & Dennis Kalma. Wetland Plants of the Adirondacks: Ferns, Woody Plants, and Graminoids (Trafford Publishing, 2011), p. 21.

Donald D. Cox. A Naturalist's Guide to Wetland Plants. An Ecology for Eastern North America (Syracuse University Press, 2002), pp. 84-85.

Ronald B. Davis. Bogs and Fens. A Guide to the Peatland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 246-247.

Gary Wade et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380, p. 5. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169. Retrieved 22 January 2017, p. 9.

Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, and Arnold L. Nelson. American Wildlife & Plants. A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits (Dover Publications, 1951), p. 369.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 73-76.

Plants for a Future. Osmunda regalis - L. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Royal Fern. Osmunda regalis L. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

Iowa State University. BugGuide. Olethreutes osmundana. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

Allen J. Coombes. Dictionary of Plant Names (Timber Press, 1994), p. 132.

"What the Latin Name Means II," American Fern Journal, Volume 11, Number 1 (January-March 1921), pp. 25-27. Retrieved 10 January 2018.