Birds of the Adirondacks:

Chestnut-sided Warbler (Setophaga pensylvanica)

The Chestnut-sided Warbler (Setophaga pensylvanica) is a greenish-yellow, black, and white warbler with a chestnut streak on its sides. It breeds in early successional habitats in the Adirondacks.

The Chestnut-sided Warbler is a member of the New World Warbler or Wood Warbler family (Parulidae). New World Warblers are small, primarily insect-eating songbirds which winter in warmer areas to the south and migrate north each spring to breed.

- The Chestnut-sided Warbler is currently assigned to the Setophaga genus, a large group which also includes many other warblers that breed in the Adirondacks, including the Palm Warbler, Cape May Warbler, Northern Parula, Blackburnian Warbler, and Yellow Warbler. The name Setophaga is derived from the Greek ses ("moth") and phagos ("eating").

- The Chestnut-sided Warbler was previously assigned to the Dendroica genus. In 2011, as part of a larger rearrangement of Wood Warbler taxonomy, based on DNA studies, the Dendroica genus was merged with the Setophaga genus, which now contains at least 33 species. Some older publications still list the Chestnut-sided Warbler as Dendroica pensylvanica.

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Identification

Chestnut-sided Warblers in breeding plumage are fairly easily recognized. The main colors to look for are yellowish-green, white, black, and chestnut.

- The underparts are white with distinctive chestnut (reddish-brown) markings down the side.

- The breast and throat are white.

- The face is white, marked with black, with a black eye stripe and black malar stripe (the area bordering the throat).

- The forehead and cap are greenish-yellow.

- The Chestnut-sided Warbler has yellowish wing bars.

- This warbler has a yellowish-green back heavily streaked with black.

- The bill is black or slate black.

- The tail is white with dark borders.

- The legs are dark.

Breeding males have a bright yellow crown, yellow and black stripes on the back, a black and white face with white cheeks and a black mask, and extensive chestnut coloration. The amount of chestnut on the side varies. Nonbreeding males have a green crown and back, spotted blackish upper parts, a gray face, white eye rings, and extensive chestnut on the flanks.

Breeding females have duller coloration than males. They have less streaking on the back, a yellow crown, and chestnut sides. However, the chestnut streaking is less extensive than on the breeding male. Breeding females have broad yellowish wing bars and a dull black or slate gray line through the eye. Nonbreeding females have little or no chestnut on the flanks, a gray face, a yellow-green crown and nape, and white eye rings.

Immature Chestnut-sided Warblers resemble fall adult Chestnuts. They have less rusty streaking than adult females, grayish cheeks and underparts, and white eye rings. The bills of juvenile Chestnut-sided Warblers are brownish slate, with a dull white base and a slate gray tip; the legs and feet are slate color. First-fall females are drabbest overall, with minimal or no chestnut coloration on the flanks.

One other warbler which may be confused with Chestnut-sided Warblers is the Bay-breasted Warbler. Bay-breasted Warblers breed in the Adirondack region, but are much less numerous here than the Chestnut-sided Warblers.

- Breeding male Bay-breasted Warblers can be distinguished from Chestnut-sided Warblers by their rusty crown (contrasting with the Chestnut-sided Warbler's yellow crown) and dark cheeks (contrasting with the Chestnut-sided Warbler's white cheeks). Male Bay-breasted Warblers have a rusty throat, in contrast to the Chestnut-sided's white throat.

- Nonbreeding female and immature male Bay-breasted Warblers may be distinguished from their Chestnut-sided counterparts because they lack the complete bold eye ring seen on nonbreeding Chestnut-sided Warblers. In addition, nonbreeding female and immature male Bay-breasted Warblers have white wing bars, as opposed to the yellowish wing bars of Chestnut-sided Warblers.

Chestnut-sided Warblers: Songs and Calls

Chestnut-sided Warblers have two basic song types.

- The easiest to recognize is the accented-ending song, with louder concluding notes. This song is sometimes transliterated as "pleased-pleased-pleased-pleased-ta-MEETCHA." Another mnemonic some birders find useful is "see-see-see-Miss-BeeCHER." Accented-ending songs show minimal geographic variation.

- Unaccented-ending songs lack the concluding downsweep note and are easily confused with the songs of American Redstarts and Yellow Warblers. The Chestnut-sided Warbler's unaccented songs tend to be of lower frequency and longer duration. This song is more variable, with distinct regional dialects.

Accented-ending songs are used before the arrival of females on breeding territory and prior to pairing, apparently as a way to attract females. After the birds have paired up, males sing unaccented songs before sunrise, switching to accented songs after about 20-40 minutes. As the breeding cycle progresses, the proportion of unaccented songs increases while the total amount of singing declines. Overall singing rates peak at dawn and decline through the day, with another lesser peak in the evening.

Only male Chestnut-sided Warblers sing, although females may occasionally make song-like vocalizations. Nearly all singing is done within the male's territory, usually from elevated perches in trees. Males sing and forage intermittently, hopping from branch to branch.

The Chestnut-sided Warbler uses a variety of call notes, variously described as a sharp, husky "tchip," a burry "breeet," or or a rough "zeet." Calls are used by both males and females year-round.

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Behavior

Chestnut-sided Warblers are described as active birds which are often quite tame, allowing fairly close human approach. They move by hopping on the ground or in foliage, climbing branches by hopping and fluttering, often with their tails partly cocked and wings slightly drooped. They are not known to walk.

During breeding season, Chestnut-sided Warblers are highly territorial, socializing only in breeding pairs. During migration, they may join flocks and can be seen foraging with other species, such as Black-capped Chickadees.

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Migration

Chestnut-sided Warblers are long-distance migrants that winter in Central America. They migrate primarily at night, with their flight generally finished before dawn.

Males begin spring migration about five days before females. They usually reach their breeding territory by the second week in May in the southern portion of their breeding range and by late May in the northern portion of their breeding range. The fall migration back to wintering grounds generally begins in mid-August to late September, with the birds migrating through the eastern part of the US, arriving on wintering grounds during October.

In the Adirondack Park, Chestnut-sided Warblers appear to arrive starting the first week in May. The pattern of eBird sightings in the six core Adirondack counties (Essex, Hamilton, Warren, Herkimer, Clinton, and Franklin) show the highest number of reports in the last three weeks in May through the first week in July.

Chestnut-sided Warblers apparently begin leaving breeding grounds in the Adirondack region in August. Sighting reports for the six core Adirondack counties were less frequent in August and the first half of September. By the first week in October, most Chestnut-sided Warblers appear to have left the Adirondack region.

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Diet and Foraging

Like other warblers, Chestnut-sided Warblers are insect eaters, although they may consume some fruit on their wintering grounds. The main items on their menu include the larvae of moths, butterflies, and flies. They may also consume adult moths, small grasshoppers, beetles, and spiders. Even on their wintering grounds, where they may eat more berries, insects comprise over 90% of their diets.

Chestnut-sided Warblers forage by searching for insects on the undersides of leaves. They focus mainly on the low to mid-levels of the canopy, between the ground and the tops of small trees or in the lower branches of larger trees. However, they may occasionally be seen near the ground and throughout the canopy. In contrast to nuthatches and Black-and-White Warblers, which are commonly seen foraging on trunks and main branches, Chestnut-sided Warblers rarely forage on the limbs and trunks of trees.

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Breeding and Family Life

Chestnut-sided Warblers place their nests fairly close to the ground (2-3 feet high), in dense shrubs or deciduous saplings. The female chooses the nest site and constructs the nest. The female produces a clutch of four eggs. Incubation lasts 11 to 12 days, with incubation by the female only.

Both parents reportedly feed the nestlings, which leave the nest about 10-12 days after hatching. In New York State, the second breeding bird survey (2000-2005) reported nestlings from 17 May to 6 August. Sightings of fledglings were reported from 19 May to 30 August.

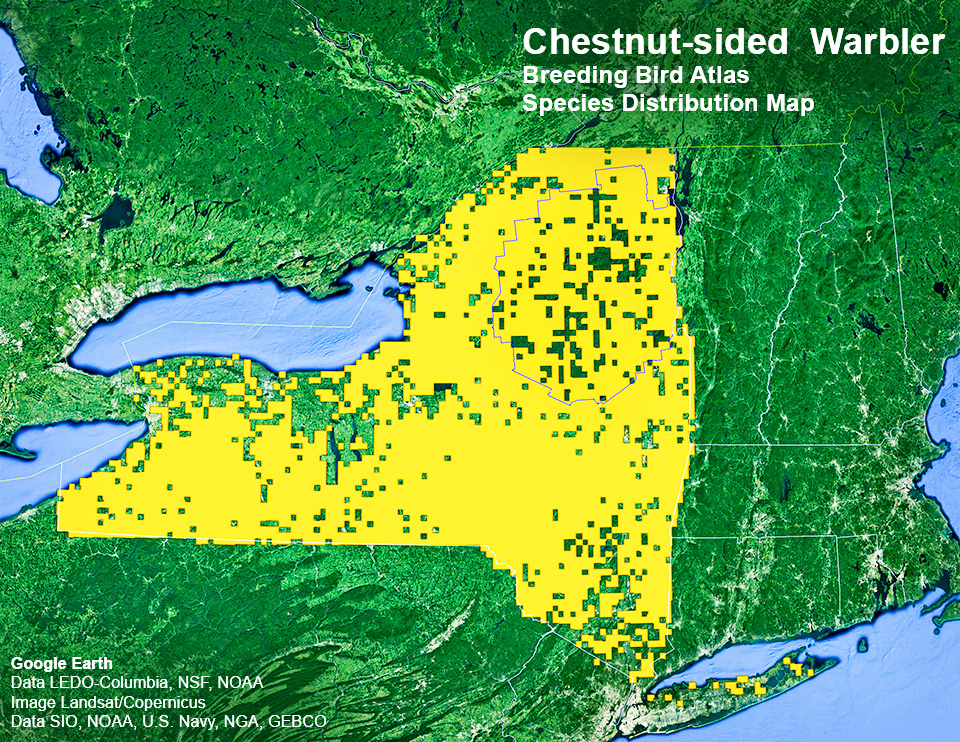

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Distribution

Chestnut-sided Warblers are one of the more common warblers. Partners in Flight estimates a global breeding population of 19 million, with 70% in Canada and 30% in the US. The main breeding range for this warbler includes southern Canada and the northeastern region of the United States, southward through the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia.

The range and population of Chestnut-sided Warblers reflects changes in its preferred habitat: early successional deciduous forests. In the early 1800s, Chestnut-sided Warblers were rarely seen, as most areas were covered with mature forests. Then large tracts of forested land were cleared for agriculture or logging. This was followed by a significant increase in successional habitat as logged-over tracts regenerated and farmland was abandoned, resulting in a major expansion in the Chestnut-sided Warbler population.

Chestnut-sided Warbler populations are now on the decline, primarily because many early successional forests have now matured and logging activity has declined, especially in the eastern US. Partners in Flight estimated a 42% decline in the population of Chestnut-sided Warblers between 1970 and 2014.

New York State, which is within the core of the Chestnut-sided Warbler's breeding range, reflects these trends. At one time, this warbler was rarely seen in the state. Populations probably increased as cleared areas of forests reverted to early-successional forests in the early to mid-1900s, then decreased in the latter part of the 20th century as early successional forests matured.

- The Breeding Bird Survey for 1980 to 1985 found confirmed or probable breeding sites throughout the state, with some gaps in the parts of the Adirondacks, Finger Lakes Area, Long Island, the Catskills, and western New York near the Great Lakes. Clusters of confirmed breeding sites were found in the Tug Hill Area and the south-central Adirondacks.

- The 2000-2005 Breeding Bird Atlas revealed a similar pattern, with confirmed or probable breeding pairs distributed throughout the state. There were some gaps in the Finger Lakes area, western New York State near Lake Ontario, Westchester County, and Long Island. Confirmed breeding bird sites were clustered in the southwestern part of the Adirondacks, as well as the Tug Hill area. Other clusters were found in the southwestern part of the Catskill area.

Chestnut-sided Warbler: Habitat

Like the Mourning Warbler, the Chestnut-sided Warbler is an early successional species, nesting in second-growth deciduous forest.

- Chestnut-sided Warblers are found in brushy thickets, bushy pastures, forest openings, the edges of forests, and neglected roadsides. They generally avoid conifer-dominated habitats, mature deciduous forests, areas of intense agriculture, and developed areas in towns and cities.

- Chestnut-sided Warblers are associated with three types of early successional habitats: areas altered by natural disturbances (such as storms, beaver activity, or fire), old fields, and regenerating forests after logging. This warbler appears to be more abundant in recently logged areas, as compared with burned areas.

Ecological communities in New York State where Chestnut-sided Warblers breed include Successional Northern Hardwoods, Successional Shrubland, and Pitch Pine Heath Barrens.

Where to find Chestnut-sided Warblers in the Adirondacks

Adirondack Birding Sites for Chestnut-sided Warblers

- High Peaks Region

- Lyon Mountain

- Northville-Placid Trail (Long Lake)

- Northern Region

- Massawepie Mire

- Southern Region

- Pillsbury Mountain

- Sacandaga River – West Branch

- Tongue Mountain

- West Central Region

- Moose River Plains

- Wakely Mountain

- South Inlet

- Raquette Lake Inlets

- Woodhull Lake

- Wheeler Pond Loop

- Beaver Lake

- Whetstone Gulf

Source: John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack birders in search of Chestnut-sided Warblers have a variety of birding sites to choose from, particularly in the west-central region of the Adirondack Park, as listed in Peterson and Lee's Adirondack Birding guide. Their list of birding sites for Chestnut-sided Warblers includes the Moose River Plains in Hamilton County, the Wheeler Pond Loop in Herkimer County, Massawepie Mire in St. Lawrence County, and Lyon Mountain in Clinton County.

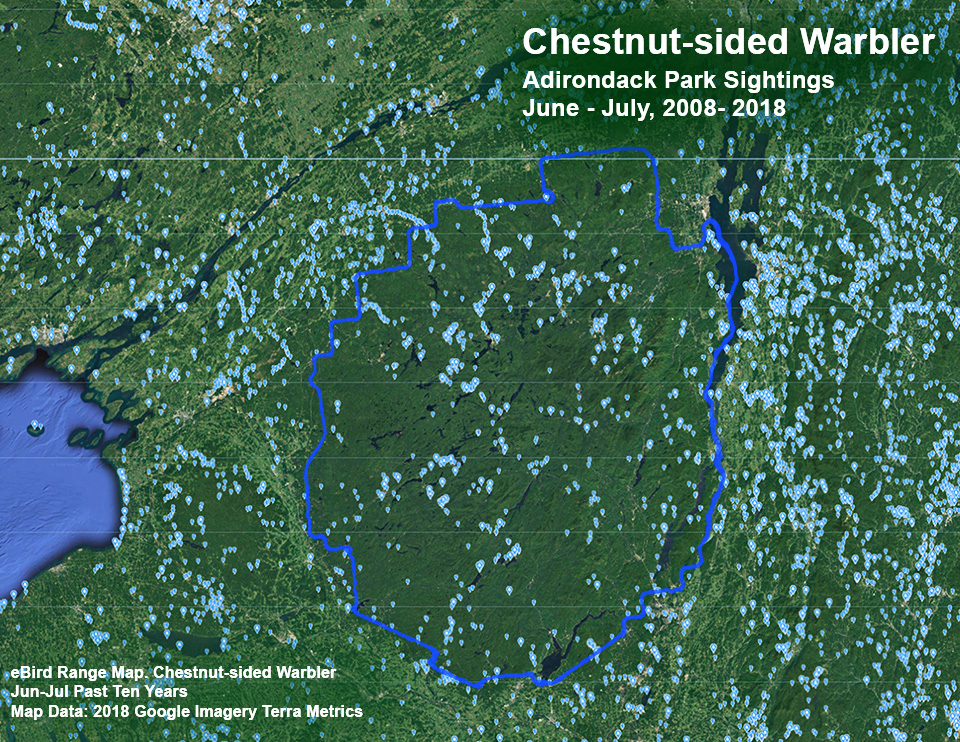

The pattern of eBird sightings for the Chestnut-sided Warbler during breeding season is roughly consistent with the Peterson/Lee recommendations and the findings of the two New York State Breeding Bird Surveys.

- As with the Mourning Warbler, sightings of the Chestnut-sided Warbler reported through eBird are more numerous outside the park than within the Blue Line. This is partly due to the fact that there are more birders outside the Park. Another key factor is that the early successional habitat favored by Chestnut-sided Warblers is more widespread in other parts of the state.

- The list of eBird reports for Chestnut-sided Warbler includes clusters of sightings in popular birding sites, such as Spring Pond Bog, the Paul Smith's College VIC, Bloomingdale Bog (both the north and south entrances), Moose River Plains, Massawepie Mire, and Wheeler Pond Loop.

Among the trails covered here, the most likely locations to look for Chestnut-sided Warblers include the brushy areas on the edges of the fields at the John Brown Farm Trails, the second growth areas along the Logger's Loop Trail as it passes through the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area (FERDA) plots, early successional habitats along Hulls Falls Road and the Jackrabbit Trail, and on forest edges near the Cemetery Road Wetlands.

References

American Ornithological Society. Checklist of North American Birds. Setophaga pensylvanica. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

Avibase. The World Bird Database. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of North America. Subscription Web Site. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Species Maps. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

Xeno-canto Database. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

Lang Elliot. Music of Nature. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

G.A. Gough, J.R. Sauer, and M. Iliff. Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter. 1998. Version 97.1. Chestnut-sided warbler. Dendroica pensylvanica. Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

USGS. Longevity Records of North American Birds. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

Boreal Songbird Initiative. Guide to Boreal Birds. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Dendroica pensylvanica. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

Audubon. Guide to North American Birds. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

Bird Watcher's Digest. Bird Identification Guide. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distributions Map (Google Earth). Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 1980-1985. Release 1.0. Updated 6 June 2007. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Breeding Bird Atlas: Species Distribution Map, 2000-2005. Release 1.0. Updated 11 June 2011. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

Timothy J. Fox, "Chestnut-sided Warbler. Dendroica pensylvanica," in Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008), pp. 482-483, 649.

Stephen W. Easton, "Chestnut-sided Warbler. Dendroica pensylvanica," in Robert F. Andrle and Janet R. Carroll (Eds.) The Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 1988). pp. 370-371.

Geoffrey Carleton. Birds of Essex County, New York. Third Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1999), p. 35.

Charles W. Mitchell and William E. Krueger. Birds of Clinton County. Second Edition (High Peaks Audubon Society, 1997), pp. 98, 126.

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993), p. 201, Plate 43.

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008), pp. 88-90, 105-107, 140-144, 147-149, 153-157, 163-168, 178-180, 186-192, 196-198, 202-204, 209.

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Trend Estimate by Species. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Version 2.07.2017. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013. Population Estimates Database, version 2013. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Setophaga pensylvanica. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Partners in Flight. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan. 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States, p. 111. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Partners in Flight. Bird Conservation Plan for the Adirondack Mountains, pp. 10-12, 23-25, 35-37 Retrieved 23 November 2018.

Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle. The Warbler Guide (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 33, 39-40, 52, 66-67, 90, 144, 152, 158, 234, 238-247, 244, 282, 305, 436, 473, 489, 537, 5420543, 546.

Chris G. Earley. Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 36-39.

Frank M. Chapman. The Warblers of North America. Third Edition (D. Appleton & Company, 1907), pp. 187-192.

Jon Curson, David Quinn and David Beadle. Warblers of the Americas. An Identification Guide (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), pp. 116-118, Plate 6.

Jon L. Dunn and Kimball L. Garrett. A Field Guide to Warblers of North America (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997), pp. 232-239, Plate 10.

Douglass H. Morse. American Warblers: An Ecological and Behavioral Perspective (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 151-152, 154-157, 262-264.

Ludlow Griscom, Alexander Sprunt, Jr. et al., Eds. The Warblers of North America (The Devin-Adair Company, 1957), pp.166-167, Plate 20.

Arthur Bent. Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers (Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 203, 1953), pp. 367-379. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 97, 101-102, 125. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2015. Online Conservation Guide for Pitch Pine-Heath Barrens. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Sightings. Chestnut-sided Warbler. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

Aretas A. Saunders. "The Summer Birds of the Northern Adirondack Mountains," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin. Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 326-499. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Theodore Roosevelt, "The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, N.Y.," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 5. Number 3 (September 1929), pp. 501-504. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Perley M. Silloway, "Relation of Summer Birds to the Western Adirondack Forest," Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 4 (March 1923), pp. 396-486. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Elon Howard Eaton. Birds of New York (New York State Museum, 1914), pp. 16, 22, 27-28, 32-34, 411415. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

C. Hart Merriam, "Preliminary List of Birds Ascertained to Occur in the Adirondack Region. Northeastern New York," Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, Volume 6, Number 4 (October 1881), pp. 225-235. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

David Sibley. The New Wood-Warbler Taxonomy. 23 June 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2018.