Amphibians & Reptiles of the Adirondacks:

Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer)

The Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer) is a small woodland frog with a loud, high-pitched call that dominates many wetland areas in the Adirondacks in the spring.

As is the case for several other amphibians native to the Adirondack region, the Spring Peeper's taxonomic status and scientific name been repeatedly revised.

- The Spring Peeper was once assigned to the genus Hyla, which was at that time a large genus of more than 300 species. In the mid-nineteenth century, it was referred to as Hyla pickeringi; its scientific name was later changed to Hyla crucifer.

- After a major revision of the tree frog family, the Spring Peeper was reassigned to the genus Pseudacris, commonly known as the chorus frogs. The Spring Peeper's scientific name was changed to Pseudacris crucifer. The genus name (Pseudacris) is derived from the Greek pseudes (false) and akris (locust), which may be a reference to the idea that the trill of the frogs in this genus are similar to those of an insect. The species name (crucifer) comes from the Latin cruces, meaning "cross" – a reference to the cross-shaped pattern on the frog's back.

- The two subspecies – Northern Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer crucifer) and Southern Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer bartramiana – are no longer recognized.

The currently used English name (Spring Peeper) is a reference to the frog's high-pitched cheep that resounds in and near there aquatic breeding sites in spring. Other early nonscientific names for this species include Pickering's Tree Frogs, Pickering's Tree Toad, Pickering's Hyla, and Peeper.

Spring Peeper: Identification

Adult Spring Peepers are tiny frogs, only about an inch in length when full grown. Males are slightly smaller (¾ inch to 1 inch in length) than females (1 to 1¼ inches in length). The skin is smooth. The background color is light tan to dark brown. Spring Peepers are said to have some color-changing ability and can appear darker during the day than at night.

The Spring Peeper's most distinctive marking is a characteristic dark-colored "X" on the back, which helps the frog blend into the leaf litter and low vegetation where it spends its time outside of breeding season. A dark V-shaped line connects the eyes. There is sometimes a dark patch surrounding the eye and usually dark bars on the legs. The underside is light and usually unmarked. The toe tips are only moderately expanded. Spring Peepers do not have webbing between the toes.

Similar Species: Spring Peepers are somewhat similar in appearance to the Gray Treefrog (Dryophytes versicolor), another frog native to the Adirondacks. However, the Spring Peeper is much smaller and has smaller toe pads. The Spring Peeper also has smooth skin, in contrast to the warty skin of the Gray Treefrog. In addition, the Gray Treefrog has dark blotches on the back, in contrast to the cross-shaped markings of the Spring Peeper.

Spring Peeper: Behavior

Spring Peepers Calling on the Black Pond Outlet

Paul Smith's College VIC

Franklin County, NY (1 May 2021)

Spring Peepers are among the first frogs to begin calling in the spring. As the ground warms, the males (who have been overwintering on the forest floor) trek off to their breeding sites on pond edges, vernal pools, swamps, or marshes. There they begin advertising their availability for breeding with a chorus of shrill, melodious (and sometimes deafening) peeps.

Calling usually begins before actual mating, sometimes up to a week before. In New York State, calling begins in mid-March in the southern regions and mid-April in the northern areas. Early 20th century herpetologist Mary Dickerson linked the timing of Spring Peeper calling to the flowering of pussy willows, noting that peepers begin calling when the pussy willows are grey, calling both day and night when the pussy willows are in blossom, and calling only during late afternoon and night when the pussy willow's seed pods are ripening. When pussy willows begin to scatter their seeds, the Spring Peeper chorus draws to a close.

The Spring Peeper has two common calls. The most familiar call is a high-pitched, repeated "peep."

- The peep is an advertisement call, meant to attract females. Female Spring Peepers reportedly choose males based on call volume and rapidity.

- The duration and number of calls per minute seems to vary depending on temperature. Two males may alternate peeps, with the follower calling just after the end of the leader's call.

- The majority of calling occurs in the late afternoon and at night, with choruses of peeps loudest beginning at dusk and building up as it becomes darker. Depending on weather conditions, sporadic calls or chorusing may also be heard during daylight hours.

Males also emit a trill, which is used when another calling male moves close by. If the intruder does not leave, the trill may be followed by a brief physical interaction.

After the spring breeding season, the tiny amphibian travels back into the nearby woods. Some some sporadic peeping may be heard in fall, usually during a period of mild temperatures.

Spring Peepers spend their winters in forested areas, usually near wetlands, sheltering under leaf litter, logs, bark, moss, or shallow soil. They survive the freezing temperatures of winter by producing their own form of antifreeze, converting the glycogen in their liver to glucose dispersed throughout their bodies to slow the formation of ice crystals.

Spring Peeper: Diet

Adult Spring Peepers are insectivores, feeding primarily on small nonaquatic insects, such as ants, beetles, and flies. Adults also consume their shed skins. The Spring Peeper menu appears to be based on availability rather than preference, probably because invertebrate populations often fluctuate dramatically. The Spring Peeper's prey is almost entirely terrestrial; one study of the stomach contents of Spring Peepers near Ithaca, New York, found no evidence that aquatic prey is eaten.

Adult Spring Peepers reportedly feed primarily from late afternoon to early evening, while young peepers have two feeding periods: early morning and late afternoon. Peepers forage for small invertebrates in the leaf litter and surface debris of forest floors. They have also been observed in the branches of low vegetation, feeding on arthropods attracted to the flowers.

Spring Peeper tadpoles are dentivores, meaning that they feed on dead organic matter, especially plant detritus. They feed primarily at the bottom of their ponds. They also consume the eggs of crustaceans. Increased food availability in the early stages of development causes tadpoles to metamorphose earlier.

Spring Peeper: Reproduction

The Spring Peeper's breeding season is fairly prolonged, lasting two months or more. The timing of the breeding period depends on the region, occurring earlier in southern regions and as late as April to July in the North. Migration to breeding sites take place during nighttime; and the process may extend over period of weeks.

Mating is generally initiated by the female, who deposits her eggs singly or in small masses of two to 30 eggs. The eggs are usually attached to twigs or aquatic vegetation. Tadpoles hatch in four to fifteen days, apparently depending on water temperature. The tadpoles transform into froglets from 45 to 90 days later.

Spring Peeper: Distribution

Spring Peepers are found throughout much of the eastern half of the US and southeastern Canada. In Canada, Spring Peepers range from the Canadian Maritime Provinces west to southeast Manitoba. In the US, this species is found from Maine south to northern Florida and west to Minnesota and eastern Texas.

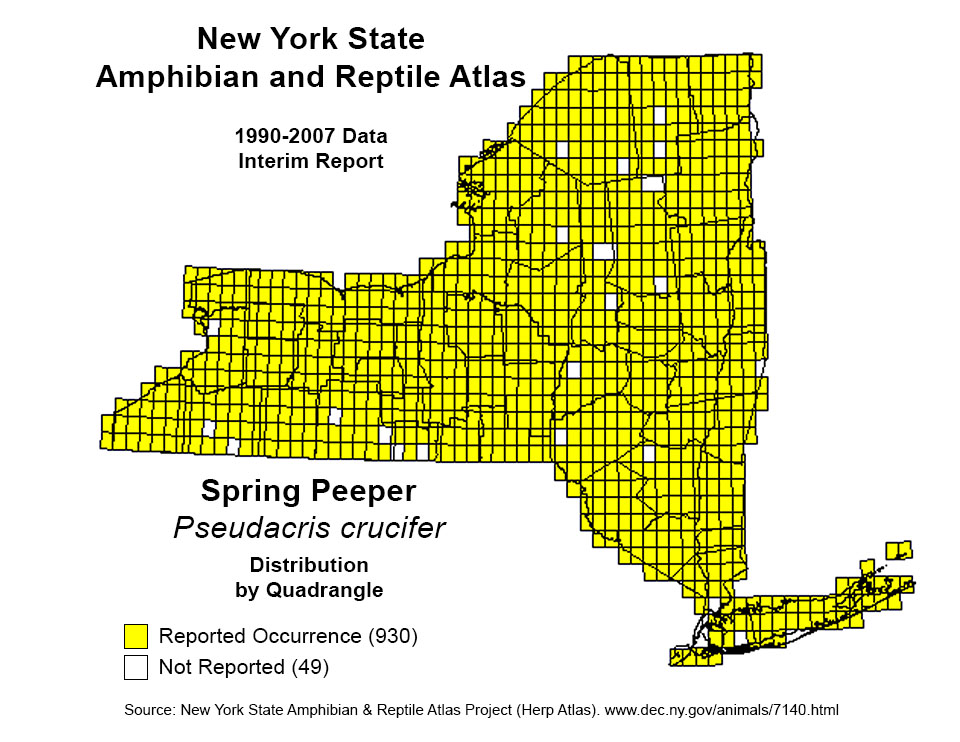

Spring Peepers are found throughout New York State. These frogs are widely distributed and commonly heard in the Adirondack Park, but less commonly seen.

The Spring Peeper is of low conservation concern, because of its large population size and the existence of thousands of sub-populations. It is judged to be a relatively secure species throughout much of its range, except in regions at the margins of its range. It is considered to be threatened in Kansas at the periphery of its range; it is protected in New Jersey. However, in many parts of its range, including in New York State, the Spring Peeper is reported to be increasing in abundance or stable.

As with all of our frogs, mortality for this species is extremely high, with an estimated one egg in a hundred producing a new frog that survives to breeding size.

- Much of the mortality occurs during the larval stage, when tadpoles are preyed on by a wide variety of predators, including brown trout, diving beetles, and salamander larvae.

- Juvenile and adult Spring Peepers fall prey to snakes, birds, and larger frogs. Although Spring Peepers use a variety of strategies to evade predators (such as flight, remaining motionless, and body inflation), their main defense against predation is their ability to change color to match the substrate, making them difficult to see within the leaf litter.

- Spring Peepers may also fall victim to vehicular traffic or human hunters. In New York State, the open season on Green Frogs extends from 15 June through 30 September. There is no bag limit, although a license is required.

Spring Peeper: Habitat

The Spring Peeper's breeding sites are diverse. They make use of both temporary and permanent wetlands; and appear to prefer open-canopied wetlands, including bogs, marshes, swamps, and roadside ditches, as well as the marshy edges of lakes, ponds, and slow-moving streams.

In the Adirondacks, Spring Peepers breed in several different wetland ecological communities, including:

The Spring Peeper's non-breeding habitats are also diverse. They inhabit a wide variety of terrestrial communities, including hardwood, mixed, and conifer forests, meadows, and forested ravines, often areas in fairly close proximity to wetlands. They appear to prefer hardwood and mixed forests to conifer forests.

Spring Peepers are commonly heard, but less commonly seen. Among the trails covered here, you will hear Spring Peepers calling in early spring to early summer on any trails that pass through or are close to wetland areas, including the Heron Marsh Trail, Boreal Life Trail, and Black Pond Trail at the Paul Smith's College VIC. Your best chance of seeing a Spring Peeper is on a damp or rainy day after the breeding season. Although they may occasionally be seen two or three feet off the ground in lower branches of a small tree or shrub, they spend most of their time on the forest floor. Look for them in the leaf litter and surface debris near the trail.

List of Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles

References

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project. Species of Toads and Frogs Found in New York. Northern Spring Peeper Distribution Map. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Nature Explorer. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

iNaturalist. Chorus Frogs. Genus Pseudacris. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

iNaturalist. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

iNaturalist. Adirondack Park Observations. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Adirondack Amphibians and Reptiles. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Amphibian Species of the World 6.0. Pseudacris Fitzinger. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

National Wildlife Federation. Wildlife Library. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 48-49, 53-54 70-71. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Pine Barrens Vernal Pond. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Shallow Emergent Marsh. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2022. Online Conservation Guide for Vernal Pool. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Virginia Herpetological Society. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

C. Kenneth Dodd Jr. Frogs of the United States and Canada (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), pp. 331-348. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Roger Conant and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Third Edition (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1991), pp. 45-46, 325. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stack-pole Books, 1995), pp. 160-165.

James P. Gibbs, Alvin R. Breech, Peter K. Dicey, Glenn Johnson, John L. Berle, Richard C. Bother. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New York State. Identification, Natural History, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 130-133.

James M. Ryan. Adirondack Wildlife. A Field Guide (University of New Hampshire Press, 2008), p.101.

Arthur C. Pulse. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pennsylvania and the Northeast (Cornell University Press, 2001), pp. 151-155. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

James H. Harding and David A Mifsud. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. Revised Edition (University of Michigan Press, 2017), pp. 133-136.

Richard M. DeGraaf and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution (University Press of New England, 2001), pp. 40, 396-399, 423-426. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Lang Elliott, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. The Frogs and Toads of North America: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification, Behavior, and Calls(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009), pp. 76-79. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

John L. Behler and F. Wayne King. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), p. 406, Plate 173.

Thomas F. Tyning. A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles (Little, Brown and Company, 1990), pp. 36-45. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

Mary C. Dickerson. The Frog Book: North American Toads and Frogs, with a Study of the Habits and Life Histories of Those of the Northeastern States (Doubleday, Page and Company, 1906), pp. 138-148. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Birds of the World. Subscription Web Site. American Bittern, American Crow, American Kestrel, Broad-winged Hawk, Common Merganser, Eastern Kingbird, Eastern Screech Owl, Hooded Merganser, Red-shouldered Hawk, Red-shouldered Hawk. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Macaulay Library. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Ontario Nature. Reptiles and Amphibians. Spring Peeper. Pseudacris crucifer. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

Tom Kalinowski, "Adirondack Amphibians: Spring Peepers," Adirondack Almanack, 15 April 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Paul Hetzler, "Spring Music: Peepers, Wood Frogs, And Chorus Frogs," Adirondack Almanack, 6 April 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Tom Kalinowski, "Adirondack Amphibians: Spring Peepers in Autumn," Adirondack Almanack, 8 October 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Michael J. Caduto, "Adirondack Wildlife: Fall Peepers?" Adirondack Almanack, 28 September 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Blue Ridge Discovery Center. Spring Peeper. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Michael Rosen and Robert E. Lemon, "The Vocal Behavior of Spring Peepers, Hyla crucifer," Copeia, Volume 1974, Number 4 (December 31, 1974), pp. 940-950. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Jay A. Weber, "Herpetological Observations in the Adirondack Mountains, New York," Copeia, Number 169 (October – December 1928), pp. 106-112. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Trevor J. C. Beebee, "Effects of Road Mortality and Mitigation Measures on Amphibian Populations," Conservation Biology, Volume 27, Number 4 (August 2013), pp. 657-668. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Carl S. Oplinger, "Food Habits and Feeding Activity of Recently Transformed and Adult Hyla crucifer crucifer Wied," Herpetologica, Volume 23, Number 3 (September 20, 1967), pp. 209-217. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Wayne H. McAlister, "A Post-Breeding Concentration of the Spring Peeper," Herpetologica, Volume 19, Number 4 (January 15, 1964), p. 293. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

R.W. Russell, "Spring Peepers and Pitcher Plants: A Case of Commensalism?" Herpetological Review, Volume 39. Number 2 (May 2008), pp. 154-155. Retrieved 31 March 2020.