Ferns of the Adirondacks:

Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum)

The Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum) is a deciduous fern that grows in wet areas throughout the Adirondack Mountains and New York State. Cinnamon Ferns are among the first ferns to emerge in the spring.

This fern is a member of the Osmundaceae family, which also includes the Interrupted Fern and Royal Fern.

- Cinnamon Ferns were previously classified as Osmunda cinnamomea; and most older guide books follow this classification, as does the US Department of Agriculture and Flora of North America.

- More recent DNA evidence indicates that the Cinnamon Fern should be reclassified as Osmundastrum cinnamomeum. The newer categorization has been adopted by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System and other data bases, including the New York Flora Atlas.

- The nonscientific name (Cinnamon Fern) derives from the cinnamon-brown color of the fertile fronds. The origin of the family name (Osmundaceae) is unclear. The most popular theory is that it was originally derived from the name Osmunder – the Saxon name for the Norse god Thor, who (according to legend) hid his family from danger in a clump of these ferns.

Identification of Cinnamon Ferns

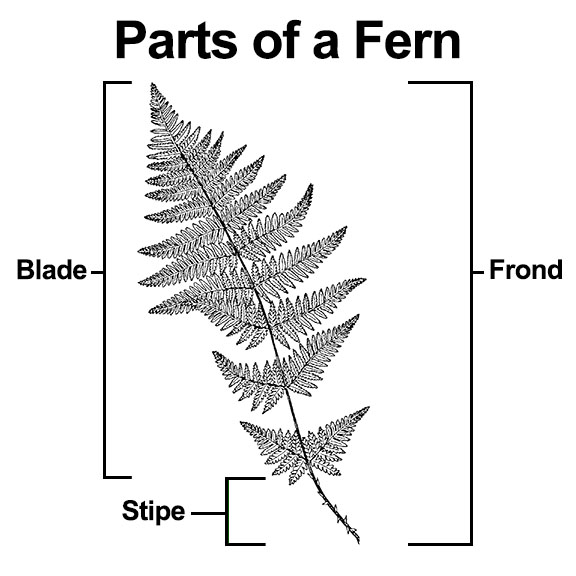

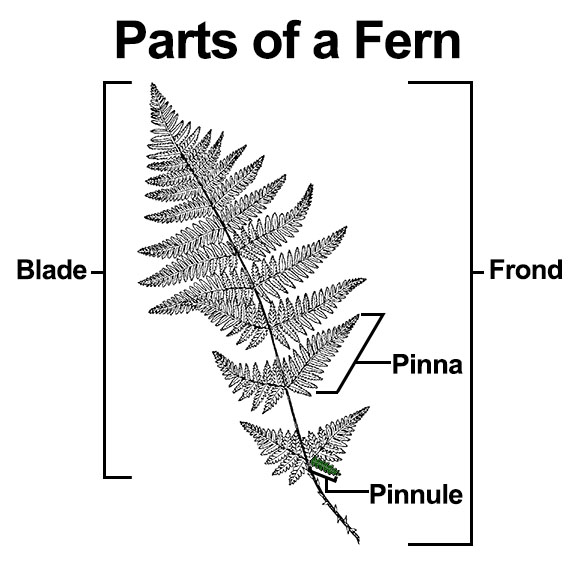

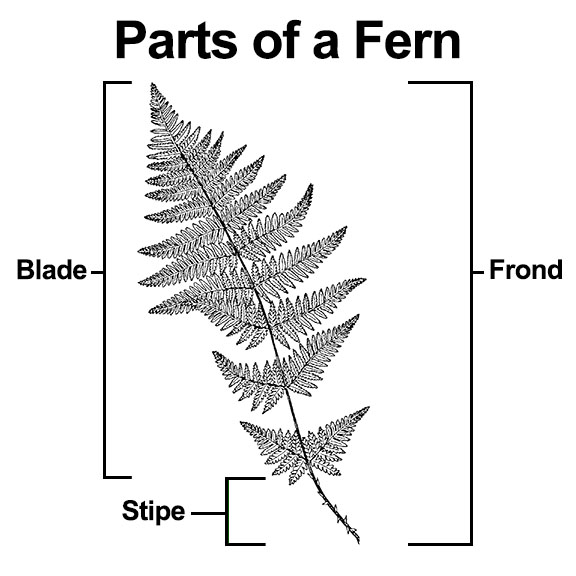

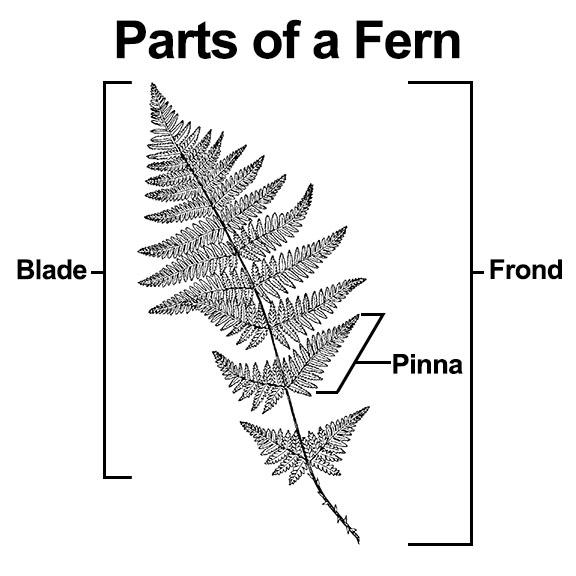

Like its relatives, the Cinnamon Fern produces separate fertile and sterile fronds Frond: The whole leaf of a fern. It includes the blade (the expanded leafy part of the frond) and the stipe (the stalk below the blade)..

Frond: The whole leaf of a fern. It includes the blade (the expanded leafy part of the frond) and the stipe (the stalk below the blade)..

- The fertile frondsFertile frond: A frond with sporangia (spore cases)., which are shorter, are the first to appear in the spring, initially as bright green wands, then turning a deep cinnamon brown.

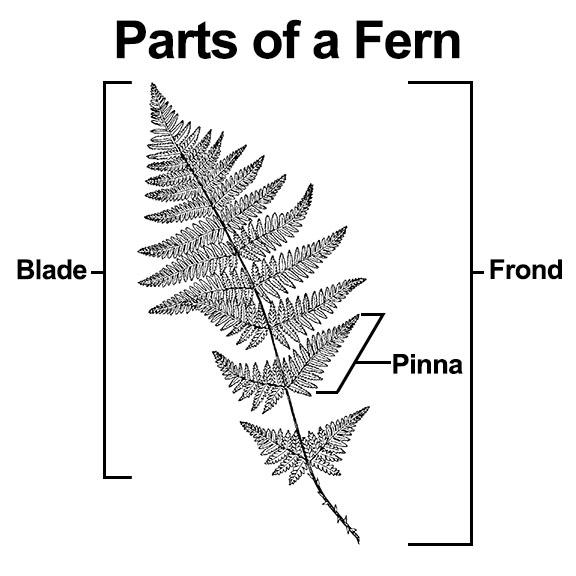

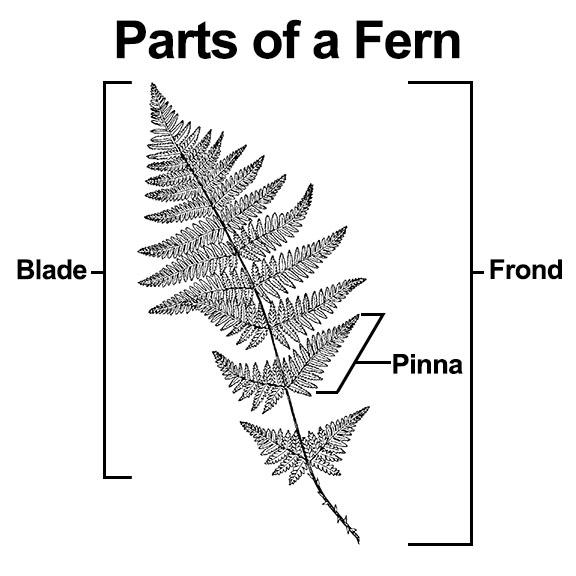

- The green, arching sterile frondsSterile frond: A frond without sporangia (spore cases). are longer (20-60 inches). The pinnae

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). (leaflets) on sterile fronds are large and narrow gradually to the tip.

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae). (leaflets) on sterile fronds are large and narrow gradually to the tip.

The fiddleheadsFiddlehead: The unfurling young frond of true ferns, which loosely resembles the ornate, curled end of a fiddle. (Synonym=crosier) of Cinnamon Ferns are covered with woolly white or reddish hairs.

Keys to identifying the Cinnamon Fern and differentiating it from other ferns include its preferred habitat and its physical characteristics.

- Cinnamon Ferns prefer wet soil, so look for it in wetland habitats, including swamps and the edges of bogs.

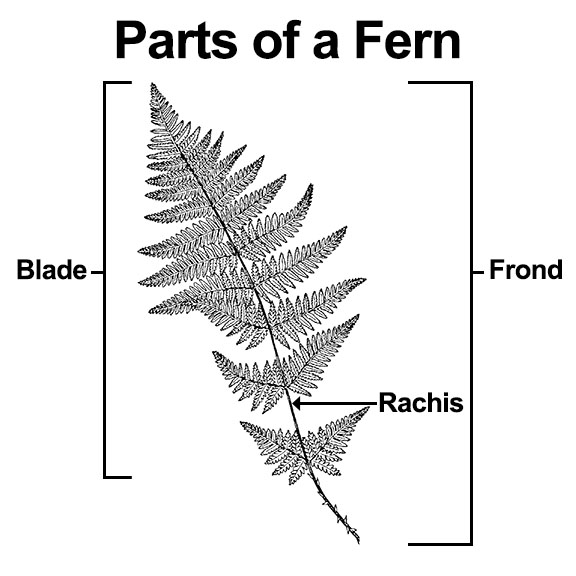

- Cinnamon Ferns have pale cinnamon-colored wool tufts on the underside of its sterile leaflets (pinnae

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae).), at the base near the rachis

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae).), at the base near the rachis Rachis: The stalk within the blade (the expanded, leafy part of the frond). (the stalk within the blade).

Rachis: The stalk within the blade (the expanded, leafy part of the frond). (the stalk within the blade).

Another clue to identifying the Cinnamon Fern is the fact that its fertile fronds are very different from its sterile fronds – a characteristic that it shares with Interrupted Ferns, Royal Ferns, and Sensitive Ferns. If you find a fern with two different types of fronds growing on a moist or wet site, it may well be one of these ferns.

- The fertile fronds of Cinnamon Ferns appear in the center of the sterile fronds. Moreover, the Cinnamon Fern's fertile fronds lack the green pinnules

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. characteristic of its two relatives.

Pinnule: A division of the pinna. characteristic of its two relatives. - The Interrupted Fern, by contrast, has fronds that are "interrupted" by two to five pairs of fertile pinnae in the midsection

- The Royal Fern's fertile fronds has fertile pinnae at the end of the blade

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond..

Blade: The expanded, leafy part of the frond.. - The fertile blades of Sensitive Ferns have beadlike pinnae

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae)..

Pinna: A primary division of the blade (plural: pinnae)..

Uses of Cinnamon Ferns

Cinnamon Ferns have been used as a food source in the past, particularly by native Americans, including the Abnaki and Menominee. However, all parts of the plant (including the fiddleheads) are now thought to be carcinogenic.

Cinnamon Ferns were used by a number of native American tribes for medicinal purposes. A decoction of the root was reportedly rubbed into affected joints to treat rheumatism. The plant was also used as a remedy for chills, headache, joint pain, and colds.

Wildlife Value of Cinnamon Ferns

Like most ferns, Cinnamon Ferns do not provide a major source of food for wildlife. However, Ruffed Grouse reportedly use the fiddleheads as a food source, and the downy wool from these ferns has reportedly been used as a nest lining by Yellow Warblers and hummingbirds. Brown Thrashers and Veeries are said to nest near the ground in the central parts of the fern's clump.

Distribution of Cinnamon Ferns

Cinnamon Ferns are widely distributed in the eastern half of the US and the southern provinces of Canada, occurring from Newfoundland to western Ontario and south to the Gulf States and New Mexico

Cinnamon Ferns are found in all New York counties and are common throughout the Adirondack Park, growing in all counties within the Blue Line.

Habitat of Cinnamon Ferns

Cinnamon Ferns prefer wet acidic soil and shady to partially shady sites. Although this plant occasionally occurs in non-wetlands, Cinnamon Ferns are more likely to be found on poorly-drained sites in swamps, marshes, and wet forests.

Some evidence suggests that Cinnamon Ferns prefer low-disturbance sites. At the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area (FERDA) at the Paul Smiths VIC, Cinnamon Ferns disappeared or diminished in abundance on most blocks in the decade after logging. Other studies suggest that Cinnamon Ferns are more abundant on unlogged than logged sites. On the other hand, Cinnamon Fern apparently increases slightly in response to fire, unless the fire is so intense that it burns the organic substrate completely.In the Adirondack Mountains, Cinnamon Ferns are found in a number of ecological communities:

For instance, the Spruce-Fir Swamp ecological community is a conifer or mixed forest typically occurring on the edge of a lake or pond or in drainage basins occasionally flooded by beaver.

- In this community, the dominant trees are usually Red Spruce and Balsam Fir, with some Northern White Cedar and Eastern Hemlock.

- The shrub layer may be sparse and include blueberries, alders, Winterberry, and Northern Wild Raisin.

- Characteristic ground-layer plants growing near Cinnamon Ferns include Bunchberry, Starflower, Goldthread, Common Wood Sorrel, Creeping Snowberry, and Dewdrop.

- Characteristic mosses include Leafy Liverwort and Big Red-stem Moss.

- Characteristic birds to look and listen for include the Golden-crowned Kinglet and the Yellow-rumped Warbler.

Cinnamon Ferns can be seen on many of the trails covered here, including the Boreal Life Trail and Heron Marsh Trail at the Paul Smiths VIC and the Heart Lake Trail, where it can be seen in the Nature Museum's Fern Garden, as well as on the Ski Slope.

List of Adirondack Ferns

References

Michael Kudish. Adirondack Upland Flora: An Ecological Perspective (Saranac, New York: The Chauncy Press, 1992), p. 81.

Boughton Cobb. A Field Guide to Ferns and their Related Families. Northeastern and Central North America. Second Edition (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005), pp. 170-173.

New York Flora Association. New York Flora Atlas. Cinnamon Fern. Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (L.) C. Presl var. cinnamomeum. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (L.) C. Presl Retrieved 4 January 2018.

United States Department of Agriculture. The Plants Database. Cinnamon Fern. Osmunda cinnamomea L. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Flora of North America. Osmunda cinnamomea Linnaeus, Sp. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Michael Burgess. A Field Guide to the Ferns of New England and Adjacent New York. pp. 96-97. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

Ronald B. Davis. Bogs & Fens. A Guide to the Peatland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (University Press of New England, 2016), pp. 242-243.

Richard Mitchell. Atlas of New York State Ferns (New York State Museum, 1984), p. 5 Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Eugene C. Ogden. Field Guide to Northeastern Ferns (New York State Museum, 1981), pp. 85-88. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

William J. Cody and Donald M. Britton. Ferns and Fern Allies of Canada (Research Branch. Agriculture Canada, 1989), pp. 126, 128-129. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

David B. Lellinger. A Field Manual of the Ferns & Fern Allies of the United States and Canada (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), pp. 120-121, Plate 123.

Anne C. Hallowell and Barbara G. Hallowell. Fern Finder. Second Edition (Nature Study Guild Publishers, 2001), p. 40.

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation. New York Natural Heritage Program. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition (March 2014), pp. 53-54, 57-58, 64-65, 69-70, 71-72, 72, 74-75, 75-76, 76. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Black Spruce-Tamarack Bog. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Hemlock-Hardwood Swamp. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Highbush Blueberry Bog Thicket. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Northern White Cedar Swamp. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Pine Barrens Vernal Pond. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Hemlock-Hardwood Peat Swamp. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Rich Sloping Fen. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Silver Maple-Ash Swamp. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce Flats. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Spruce-Fir Swamp. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

New York State. Adirondack Park Agency. Preliminary List of Species Native Within the Adirondack Park Listed Alphabetically by Scientific Name and Sorted by Habit. Volume 1, p. 59. Updated 10.23.2006. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Connecticut Botanical Society. Quick Guide to the Common Ferns of New England. Cinnamon Fern. Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (L.) C. Presl. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

Gary Wade, et al. Vascular Plant Species of the Forest Ecology Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NE-380. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mark J. Twery, et al. Changes in Abundance of Vascular Plants under Varying Silvicultural Systems at the Forest Ecosystem Research and Demonstration Area, Paul Smiths, New York. USDA Forest Service. Research Note NRS-169. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Native Plant Trust. Go Botany. Cinnamon Fern. Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (L.) C. Presl. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden. The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden. Cinnamon Fern. Osmunda cinnamomea. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

John Eastman. The Book of Swamp and Bog: Trees, Shrubs, and Wildflowers of Eastern Freshwater Wetlands (Stackpole Books, 1995), pp. 73-76.

John Eastman, "Yellow Warbler," The Eastman Guide to Birds: Natural History Accounts for 150 North American Species. Kindle Edition. (Stackpole Books, 2012).

Ellen Rathbone, "Crazy About Ferns in the Adirondacks," Adirondack Almanack, 20 January 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species Reviews. Osmunda cinnamomea. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants. Osmunda cinnamomea L. Cinnamon Fern. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

Plants for a Future. Cinnamon Fern. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Birds of North America. Subscription web site. Yellow-bellied Flycatcher. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

Charles H. Peck. Plants of North Elba. (Bulletin of the New York State Museum, Volume 6, Number 28, June 1899), p. 156. Retrieved 22 February 2017.