Birds of the Adirondacks:

Adirondack Winter Birds

Winter birding in the Adirondacks begins in late fall as the temperatures plummet and snowy days arrive. The summer migrants who use the Adirondack Mountains as a breeding ground have left for their winter ranges to the south of us. The woods which resounded with the songs of breeding birds in spring and summer are quieter. Winter, however, provides a chance to redeploy the feeders packed up the previous spring. Much of the birding action has moved to feeding stations outside our windows and to the warmer areas near the shores of Lake Champlain.

The winter birds we see and enjoy from late fall to early spring generally fall into one of three categories:

- Year-round Residents: Birds that both breed and winter in the Adirondacks

- Winter Visitors: Birds which breed to our north and move south into our area for the winter

- Champlain Valley Birds: Birds that seek warmer weather and open water near Lake Champlain

Winter Birds: Year-round Adirondack Residents

Winter Birds of the Adirondacks:

Year-round Residents

- American Crow

- American Goldfinch

- American Robin

- Barred Owl

- Black-backed Woodpecker

- Black-capped Chickadee

- Blue Jay

- Boreal Chickadee

- Brown Creeper

- Canada Jay

- Cedar Waxwing

- Common Raven

- Dark-eyed Junco

- Downy Woodpecker

- Evening Grosbeak

- Golden-crowned Kinglet

- Great Horned Owl

- Hairy Woodpecker

- Mourning Dove

- Northern Cardinal

- Northern Goshawk

- Northern Saw-whet Owl

- Pileated Woodpecker

- Pine Siskin

- Purple Finch

- Red Crossbill

- Red-breasted Nuthatch

- Red-tailed Hawk

- Ring-necked Pheasant

- Ruffed Grouse

- Sharp-shinned Hawk

- Song Sparrow

- Tufted Titmouse

- White-breasted Nuthatch

- White-winged Crossbill

- Wild Turkey

Many of our winter residents are frequent customers at bird feeders. Birds typically seen at feeders during winter include Black-capped Chickadees, Blue Jays, Downy Woodpeckers, American Goldfinches, Hairy Woodpeckers, Dark-eyed Juncos, Red-breasted Nuthatches, and Purple Finches.

The list of birds that remain over the harsh winter in the Adirondack Park interior includes, amazingly, the tiny Golden-crowned Kinglet. These active little birds can survive –40 degree nights, sometimes huddling together for warmth. The list of winter residents also includes the Canada Jay, which (unlike most birds that breed in the Adirondacks) begins its breeding cycle in the cold of winter. Our list of year-round residents also includes some birds, like the Tufted Titmouse and Northern Cardinal, which were once quite rare in the Adirondack Park interior, but have been expanding their range northward as our winters get warmer.

Black-capped Chickadee: The most numerous of the winter residents who regularly visit feeders in the Adirondacks are the Black-capped Chickadees. These active, friendly little birds are easily identifiable, with a solid black cap and bib, white cheeks, buffy flanks, and dark gray wings and tail. There are only two other birds with similar plumage:

- The Carolina Chickadee is slightly smaller than the Black-capped and has a neater edge between the black throat and the white chest. However, Carolina Chickadees are found in the southeastern US. There is a narrow band where the two species overlap, but it is well to the south of the Adirondack Park.

- The Boreal Chickadee is another of our year-round residents with a similar plumage pattern, but it has a brown cap and much smaller white cheek patch.

In contrast to many of our summer residents, Black-capped Chickadees display few obvious sexual differences. Like most of our other year-round residents, Black-capped Chickadees don’t migrate, although young birds may move long distances during post-fledgling dispersal.

Black-capped Chickadees are the nucleus of many mixed-species winter flocks, often accompanied by their more assertive side-kicks: the Red-breasted Nuthatches. Black-capped Chickadees also lead mixed flock movements in the summer. Mixed flocks begin forming toward the end of the breeding season, and include warblers, vireos, and kinglets. In fact, the most convenient way of locating migrating warblers in late summer is to listen for chickadee calls.

Black-capped Chickadees have a complex vocal array with at least 16 different kinds of vocalization. The most recognizable is the chick-a-dee call given throughout the year and consisting of four possible note types. The birds typically add more dee notes to the call in response to predators. The main Black-capped Chickadee call is the Fee-Bee, consisting of two clear notes with the second note lower in pitch. This song is used throughout the year, but is more common in late winter and spring.

Although the Black-capped Chickadee diet during the breeding season is dominated by animal food (largely caterpillars), during the winter months, Black-capped Chickadees consume both animal food (mostly insects and spiders) and plant food (mostly seeds and berries) in about equal proportions.

- These birds come readily to most types of feeders and are especially fond of sunflower and suet.

- In contrast to some of the more quarrelsome species, Black-capped Chickadees usually politely queue up for feeder access, quickly grab a seed, and then fly off to a nearby branch to consume it.

- Black-capped Chickadees show little fear of humans and will consume seeds from an upraised hand.

Black-capped Chickadees survive our harsh winters by caching food in bark, dead leaves, or knotholes. They spend very cold night roosting in thick vegetation or cavities, tucking their heads under their scapular feathers to conserve body heat.

Blue Jay: The Blue Jay – another familiar year-round resident – is a small jay, larger than an American Robin, but smaller than an American Crow. A member of the Covid family, the Blue Jay is easily recognizable, with striking blue, white, and black plumage and a perky crest that is often lowered when the bird is among family and flock members. The bird’s upperparts are various shade of blue; its underparts are grayish white. Males and females are similar, with males about 3% larger.

Blue Jays have an extensive array of vocalizations. The jay’s whisper song is a quiet mixture of clicks, chucks, and whines sometimes lasting over two minutes. The most familiar of the jay’s vocalizations is its loud “jeer” call, used as a contact call, for mobbing, and when potentially threatened. Blue Jays are also frequently heard making “pump handle calls.”

Blue Jays are also skillful mimics. They can imitate the calls of Broad-Winged Hawks, Red-shouldered Hawks, Red-tailed Hawks, and other raptors. There are several possible explanations for the jay’s mimicry of hawks. The jay may be alerting other individuals to the presence of a raptor, or it may be deceiving other species into believing a raptor is present.

Blue Jays are omnivores. They consume arthropods, acorns, soft fruits, seeds, birds eggs, nestlings, and small vertebrates. These birds are among our most faithful customers at winter feeders.

- They clearly prefer unshelled peanuts, but will also take sunflower seeds and avail themselves of the suet feeders when peanuts are not available.

- Blue Jays prefer tray or hopper feeders to hanging feeders.

- Blue Jays tend to be bullies at feeding stations; they give ground only to the squirrels who routinely raid feeders.

Blue Jays breed in a wide variety of habitats, including deciduous, coniferous, and mixed forest. They seem to prefer woodland edges to forest interiors. They are also found in cities, suburbs, and parks.

The Blue Jay is considered a resident or short-distance migrant. It is a year-round resident throughout most of its range. Although some jays migrate to the southern portions of their breeding range every year, the proportion that migrates is probably below 20% of the population, even in the northern parts of its range. Young jays are more likely to migrate than their adult counterparts.

Red-breasted Nuthatch: The Red-breasted Nuthatch is one of two nuthatch species found in the Adirondack Park. It is most frequently seen in conifer forests or mixed woodland with a strong coniferous component, in contrast to our other nuthatch – the slightly larger White-breasted Nuthatch, which prefers deciduous forests.

Red-breasted Nuthatches are blue-gray birds with a black cap and stripe through the eye, a white stripe over the eye, short, broad wings, and very short tails. The underparts are a rich cinnamon brown. Males, females, and juveniles are all quite similar in appearance, although there are some differences.

- In adult males, the top of the head is black, the upperparts bluish gray, and the underparts rufous-cinnamon.

- In adult females, the top of the head is gray blue and the underparts are paler.

- Juveniles are similar to adults, with duller head-markings and underparts.

Plumages are similar throughout the year.

Red-breasted Nuthatches are frequently seen on tree trunks and branches, creeping up, down, and sideways. They typically move in a zig zag fashion when they move downward. Flight is irregular or undulating, with most flights typically short and swift.

This bird’s most recognizable vocalization is its nasal yank-yank sound, like a tiny tin horn. Males vocalize more than females. Red-breasted Nuthatches also emit more musical sounds, including low twittering and medleys of notes, often used as contact calls when the birds are foraging in mixed-species flocks.

In summer, Red-breasted Nuthatches consume mainly insects and other arthropods. In fall and winter, they rely on conifer seeds. They also come readily to feeders, where they seem to prefer sunflower seeds and suet. They will come to both hanging feeders and platform feeders. They are not particularly fearful of humans and can be accustomed to eating out of an upraised hand. Despite their small size, Red-breasted Nuthatches are fairly aggressive and will sometimes dominate other birds at feeders.

The Red-breasted Nuthatch is considered to be a partial migrant. Populations in the northernmost part of their distribution migrate south each year. Other populations remain on their breeding grounds, except in years when cone production is poor, when they move southward in great numbers.

- Southward migrations in the northern and eastern populations are said to occur every two to three years and are inversely correlated with cone production of conifers in the breeding range.

- Red-breasted Nuthatches breeding in high-elevation montane forests show a similar pattern of movement, remaining on their breeding grounds when cone production is good and migrating to lower elevations when cone production is poor.

Purple Finch: The Purple Finch is another year-round resident in our region considered to be a partial migrant. These chunky birds are sexually dimorphic. Both males and females have large, conical beaks and notched tails.

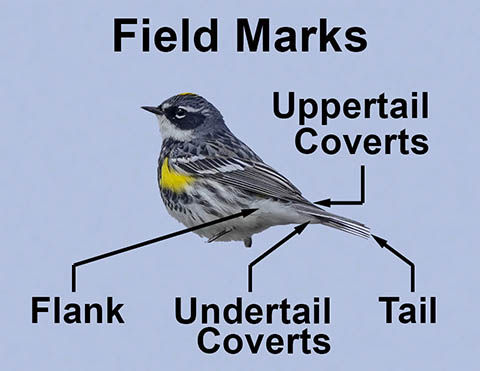

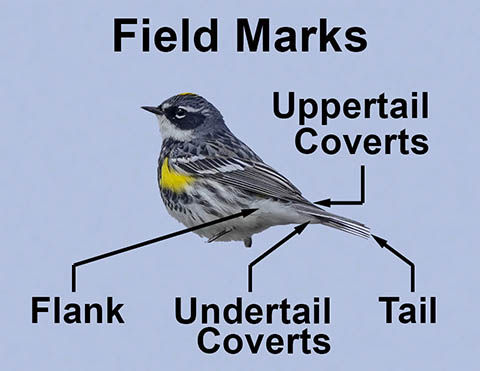

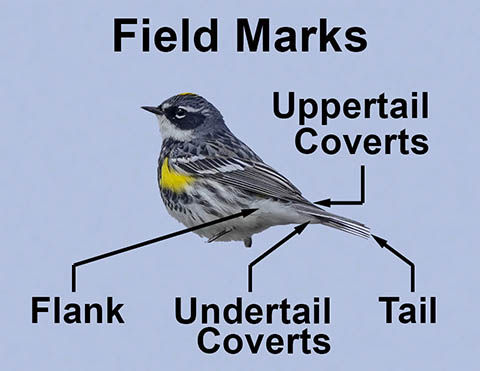

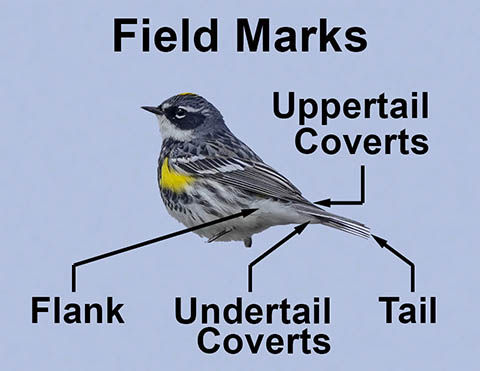

Male Purple Finches are striking birds described by ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson as a “sparrow dipped in raspberry juice.” The males have raspberry red coloration on the upperparts, neck, head, and sides. Males have reddish wingbars, brown streaks on the back and flanks. The lower belly and undertail coverts Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are white and usually unmarked.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are white and usually unmarked.

Females are drab, inconspicuous birds, with little or no red. They are strongly streaked on the back and sides of the belly and have a conspicuous light eyebrow stripe and solid ear patch. They have thin white wingbars. The background color on the belly is bright white. First-year Purple Finches are similar to the females.

Male Purple Finches sing three types of songs.

- Their warbling song is a rising and falling string of 6 to 23 rapid notes, often sung while flocking.

- The male Purple Finch’s territory song begins with a rapid series of notes on the same pitch, followed by warbling notes and ending with an accented, high-pitched note.

- Male Purple Finches also sing a series of two to five notes similar to that of the Red-eyed Vireo.

Purple Finches feed mainly on the seeds, buds, nectar, and fruit of trees. They also eat some insects, including aphids and caterpillars.

- In winter, Purple Finches will come to tube feeders, hoppers, and platforms. They prefer black oil sunflower.

- Unlike the little Black-capped Chickadees (which politely wait their turn for access to the feeder, grab a seed, and fly off to a nearby branch to eat it), Purple Finches stay at the feeder while they eat and will chase smaller birds (like the chickadee and the American Goldfinch) away to get access. They defer, however, to large birds like the Blue Jay.

The Purple Finch breeds across central and southern Canada, north central and northeastern US, southward in the Appalachians to Virginia, and along the West Coast. Within New York State, this species breeds across much of the state and throughout the Adirondack Park. It is most common in elevations above 1,000 feet. Purple Finches breed mainly in conifer or mixed forests, the edges of bogs, and riparian corridors.

The Purple Finch is considered to be a short-distance migrant. It is an irruptive species, one of several finches that move in winter in response to poor cone crops in their wintering range. During years when the cone crop in our area is good, we tend to see lots of Purple Finches at our winter feeders, since they have no need to move further south in search of food.

- The winter of 2019-2020, for example, was a good year for Purple Finches in the Adirondacks, apparently because the tree seed crops were excellent.

- Last winter (2020-2021), however, there were fewer eBird observations of Purple Finches, probably because some of our breeding Purple Finches had migrated to other areas in search of food.

American Goldfinch: The American Goldfinch is another short-distance migrant that is seen year-round in the Adirondack Park. These small finches are both sexually and seasonally dimorphic in plumage. Field marks in all seasons include a conical bill (smaller than in most finches), a pointed, notched tail, wingbars, and an absence of streaking.

- Breeding male American Goldfinches are bright yellow and black birds. The head is yellow, with a contrasting black forehead. The back and underparts are yellow. The wings are jet black with white markings. The notched tail is black, with white on the inner webs. Winter males are dull yellow beneath and olive above. The chin and throat are straw yellow and the flanks are olive-brown, with the other underparts whitish to white. The undertail coverts

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are whitish.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail. are whitish. - Breeding female American Goldfinches are much drabber than their male counterparts, with duller yellow underparts, blackish brown wings and tail, and a brownish olive back. Winter females are very similar to winter males, but duller and browner than the males.

- Immature American Goldfinches have pale yellow underparts, shading to buff on the sides. They are brown above, with dark wings marked by two buffy wingbars.

The American Goldfinch’s vocal behavior provides another identification clue. Most commonly heard in all seasons is its contact call, often given in flight. This call is a short series of three or four notes, often transliterated as “po-ta-to-chip.” Other American Goldfinch calls include a short, buzzy “dzik” threat call, commonly heard in feeding flocks. The American Goldfinch’s song is a highly variable series of warbles and twitters that can be several seconds long. This song is given by males from wires and treetops in breeding habitat.

The American Goldfinch diet is dominated by seeds, including those from thistle, sunflowers, asters, grasses, and trees. It generally forages while perched on the plant and will hang upside down from branches or thistle heads to reach seeds. This bird consumes little insect matter.

American Goldfinches readily come to winter feeders, where they are often seen of flocks of 200 or more.

- They come to most kinds of feeders (including hopper, platform, and hanging feeders) and are also seen feeding on the ground below feeders. Favored foods reportedly include sunflower seeds and black thistle.

- At feeders, American Goldfinches are relatively low on the pecking order. They will displace the ever-polite Black-capped Chickadees, but are usually driven off by the larger finches, such as Purple Finches and Pine Siskins.

- Like Purple Finches and unlike chickadees (which tend to grab a seed and fly off to a nearby tree branch to open and eat it), American Goldfinches remain at the feeder to open and eat sunflower seeds. They typically hold the seed lengthwise in their bills, crack it open with their mandibles, and hull it. They then swallow the seed and drop the husk.

American Goldfinches are widespread and common across much of North America. This bird breeds across southern Canada and the northern US, south to central Colorado, northern Texas, and northern California. The highest abundance is in the north central and northeastern US. Populations in the US have been stable since 1966, while those in Canada have shown a slight decline.

Within New York State, the American Goldfinch is more common outside the Blue Line than within. Findings from previous New York State breeding bird atlases showed this species to be present throughout the state, except in parts of the Adirondacks, New York City, and western Long Island. Preliminary findings from the New York Breeding Bird Atlas III are consistent with this pattern, showing the American Goldfinch breeding throughout the state, but missing in parts of the Adirondacks.

The American Goldfinch is considered to be a short distance migrant.

- Birds that breed in the northern parts of the goldfinch’s range (in Canada and the upper mid-western US) abandon their breeding grounds from late October to mid-December, wintering further south. Females winter farther south than males.

- The Adirondack Park falls within a large middle band which includes a year-round population, so we see American Goldfinch throughout the year. Our winter populations of American Goldfinch may include birds that have migrated from further north.

Winter Birds: Migrants from the North

Winter Birds of the Adirondacks:

Migrants from the North

Some of the birds we see in the winter, such as the Snow Bunting, are not year-round residents, but birds which breed to our north and move south into our area for the winter. Several of these species are irruptive migrants, like the Common Redpoll, which move into our region if food supplies are limited on their breeding grounds.

American Tree Sparrow: The American Tree Sparrow is one of a small number of winter visitors that winter in our area. Despite its name, the American Tree Sparrow is a ground bird that breeds at or above the tree line, nests on the ground, and forages on the ground.

The American Tree Sparrow is a medium-distance migrant that breeds in far northern North America and migrates to northern and central North American for the winter. American Tree Sparrows are usually seen in the Adirondack Park from about early November. They reportedly depart for their northern breeding grounds in late March to mid-April, although we usually see American Tree Sparrows through late April.

American Tree Sparrows are reddish-brown and gray birds. Male and female American Tree Sparrows are quite similar, and plumage does not vary much from season to season. This sparrow has a rusty cap and rusty eyeline on a gray head. Its unstreaked breast is gray to buff, usually with a dark smudge in the center. Another key field mark is the bi-colored bill; the upper mandible is dark while the lower is dark yellow with a dusky-to-black tip.

In appearance, the American Tree Sparrow may be mistaken for several other sparrows found in the upstate New York and the Adirondacks, all of which have brown and grayish plumage.

- Like the American Tree Sparrow, the Chipping Sparrow has a reddish cap and unstreaked underparts. However, the Chipping Sparrow’s cap is duskier than that of the American Tree Sparrow. The Chipping Sparrow’s eyeline is black (vice rusty in the American Tree Sparrow) and it lacks the American Tree Sparrow’s dark central breast spot and bicolored bill. In any event, Chipping Sparrows generally depart the Adirondack Park in November, so there is limited overlap in time between the two species.

- Song Sparrows have heavy streaking on the breast, in contrast to the American Tree Sparrow’s plain breast.

- Field Sparrows have a pink bill and a white eye ring. They lack the American Tree Sparrows bright rusty cap, rusty eyeline, and bicolored bill. We get very few Field Sparrows in the winter months.

The diet of American Tree Sparrows varies with the seasons. On their summer breeding grounds, they eat a wide variety of protein-rich insets, including beetles, flies, and wasps. From fall to spring, on their wintering grounds, they are almost exclusively vegetarian, consuming grass, goldenrod and other seeds.

Small flocks of American Tree Sparrows come readily to back yards, where they generally forage on the ground beneath the feeders and along the wooded edges of open areas. They tend to be a bit skittish, retreating to nearby low tree branches when disturbed.

Common Redpoll: The Common Redpoll is another winter visitor that breeds north of us. These small finches are brown and white with two white wing bars, heavily streaked sides, and streaked undertail coverts Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail.. They derive their name from the red patch on the crown or poll. The bill is yellow with black at the tip.

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail.. They derive their name from the red patch on the crown or poll. The bill is yellow with black at the tip.

- Adult males have a bright pink wash on the breast and rump.

- Adult females are similar to adult males, but are darker with a smaller red forecrown and little pink. They are also more heavily streaked.

Common Redpolls are very difficult to distinguish from Hoary Redpolls, with which they are sometimes seen in mixed winter flocks. Hoary Redpolls have a smaller bill and are paler overall, with less streaking on the sides. Hoary Redpolls also have unstreaked undertail coverts Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail..

Undertail Coverts: The short feathers beneath the tail..

The Common Redpoll is an irruptive migrant that breeds in boreal and taiga regions of both the Old and New World Arctic. Some individuals remain within their breeding grounds in winter if food is available. However, Common Redpolls move south in large numbers during winters in response to a failure in seed-crop production among high latitude tree species such as spruce and birch.

Common Redpolls are seen in fairly large numbers in our area in irruptive years. During irruptive years, Common Redpolls are generally seen in the Adirondacks from November through mid-April.

- The winters of 2010/11, 2012/13, 2014/15, 2018/19, and 2020/21 were particularly good years for Common Redpolls in the Adirondack Mountains.

- The fall 2020/winter 2021 irruption, which involved not just Redpolls but Pine Grosbeaks and Evening Grosbeaks, is considered to be a superflight of finches.

- The winter of 2021/2022 is not predicted to be an irruptive year, since the seed crop for birches, alders, and spruce is considered to be average to good.

Common Redpolls are very social birds. Outside the breeding season, they generally travel in flocks of up to fifty individuals that forage on birch catkins. Common Redpolls reportedly subsist almost entirely on a diet of birch seeds during winter. During irruptive years, small flocks of Common Redpolls congregate on winter feeders. They reportedly prefer thistle and nyjer, but will also take black oil sunflower and suet.

Winter Birds: Champlain Valley Birding

Winter Birds of the Adirondacks:

Champlain Valley

- American Black Duck

- American Wigeon

- Bald Eagle

- Barrow's Goldeneye

- Bohemian Waxwing

- Bufflehead

- Canvasback

- Cedar Waxwing

- Common Goldeneye

- Common Merganser

- Common Redpoll

- Cooper's Hawk

- Great Black-backed Gull

- Greater Scaup

- Herring Gull

- Hooded Merganser

- Horned Grebe

- Horned Lark

- Lesser Scaup

- Mallard

- Northern Flicker

- Northern Harrier

- Northern Pintail

- Northern Shrike

- Pine Siskin

- Redhead

- Red-bellied Woodpecker

- Red-tailed Hawk

- Ring-billed Gull

- Ring-necked Duck

- Rough-legged Hawk

- Sharp-shinned Hawk

- Snow Bunting

- Snowy Owl

In addition to the hardy birds who spend their winters in the Adirondack interior, a second cast of birding characters can be found in the warmer Champlain Valley – a center for cold-weather birding in the Adirondack Park. Lake Champlain remains open for much of the winter, so it attracts a large number of ducks and other aquatic birds that had abandoned their breeding territories in the Adirondack interior earlier in the fall. A number of raptors also use the lake area as a flyway and remain nearby as long as the weather allows.

Ring-billed Gull: The Ring-billed Gull is the most common gull regularly seen in New York State. It is one of two gulls that breed in the Adirondack Park, the other being the Herring Gull. This species was nearly eradicated by humans between the mid-nineteenth century and 1920, but has since recovered.

Ring-billed Gulls are medium-sized gulls, about the size of a pigeon with longer wings. The Ring-billed Gull has a short, slim yellow bill with a black band around it and a square-tipped tail. Adult Ring-bills have clean gray upper parts, a white head, body and tail, yellow legs, and black wingtips spotted with white. Nonbreeding adults have brown streaked heads. There is little sex-specific variation in plumages, although males are significantly larger than females. Gulls during their first two years are a mixed brown and gray, with a pink bill and pink legs.

Ring-billed Gulls are graceful flyers, circling and hovering acrobatically while looking for food. This species is an opportunistic feeder that consumes mostly fish, insects, earthworms, grains, and garbage. They often congregate around humans, at dumps, parking lots, docks, harbors, and freshly plowed field. They are often found in and around suburban, urban, and agricultural areas.

Ring-billed Gulls are quite noisy. They have a varied vocal array, with numerous adult calls and complex variations. Most commonly heard is a high-pitched rising squeal, followed by a series of short notes.

The Ring-billed Gull breeds in southern Canada and the northern US. The core of the birds’ breeding range is central Canada’s boreal region, southward to northern California, Wyoming, Minnesota, and the Great Lakes region. New York State is on the southeastern edge of its breeding range.

- The 2000-2005 New York State Breeding Bird survey identified only a limited number of blocks with confirmed breeding activity, mostly along Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, and the St. Lawrence River.

- Preliminary results from the 2020-2024 Breeding Bird Atlas reveal a similar pattern, although several additional breeding blocks have been confirmed in the Adirondack interior and on the shore of Lake Champlain.

The Ring-billed Gull is a partial, mid- to long-distance migrant. Most individuals depart their breeding regions in late summer and early fall to winter in warmer areas. As lakes freeze over in the Adirondack interior, these gulls (which are frequently seen throughout the Adirondacks during the warmer months) gradually disappear in search of open water. Winter birders in the Adirondacks can find Ring-billed Gulls, along with a host of other gulls and waterfowl, along the Lake Champlain coast.

Bufflehead: Bufflehead are among the many waterfowl that can be seen during the winter months on Lake Champlain. The Bufflehead is North America’s smallest diving duck, with a large, rounded head and short, wide bill. Bufflehead are sexually dimorphic, both in size and color.

- Adult male Bufflehead are striking birds. The head is black, glossed green and purple, with a large white patch. The back is black and the underparts white. The wings are black, with a large white patch.

- Female Bufflehead and first-year males are drabber. They have a dark brown head, back and wings and pale gray underparts. They have an oval, white cheek patch and a white wing patch on the wings. Female Bufflehead are significantly smaller than males.

The Bufflehead is a medium-distance migrant that breeds in boreal forest and aspen parkland in Canada and Alaska, nesting in holes excavated by Northern Flickers. Birds that breed west of the Rockies migrate to the Pacific Coast, while Bufflehead that breed in central Canada migrate east or south.

In the interior Adirondack Park, we see Bufflehead in the spring (late March through the third week in May), as they are migrating north to their Canadian breeding grounds, and in the fall (mid-October through mid-December) as they are migrating south. In the winter, Adirondack birders can also find Bufflehead along the Lake Champlain coast from November through the end of April. They are usually found in small flocks of five to ten birds during the winter. During migration, larger flocks may be seen.

Bufflehead are diving ducks who consume aquatic invertebrates, crustaceans, and mollusks, as well as some plant matter in fall and winter. These ducks usually swallow their food while underwater. Bufflehead dives last about 12 seconds, after which they bob to the surface and spend another 12 seconds before diving again.

References

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. All About Birds. American Black Duck, American Crow, American Goldfinch, American Robin, American Tree Sparrow, American Wigeon, Bald Eagle, Barred Owl, Barrow's Goldeneye, Black-backed Woodpecker, Black-capped Chickadee, Blue Jay, Bohemian Waxwing, Boreal Chickadee, Brown Creeper, Bufflehead, Canada Jay, Canvasback, Cedar Waxwing, Common Goldeneye, Common Merganser, Common Raven, Common Redpoll, Cooper's Hawk, Dark-eyed Junco, Downy Woodpecker, Evening Grosbeak, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Great Black-backed Gull, Great Horned Owl, Greater Scaup, Hairy Woodpecker, Herring Gull, Hoary Redpoll, Hooded Merganser, Horned Grebe, Horned Lark, Lesser Scaup, Mallard, Mourning Dove, Northern Harrier, Northern Pintail, Northern Saw-whet Owl, Northern Shrike, Northern Shrike, Pileated Woodpecker, Pine Grosbeak, Pine Siskin, Purple Finch, Red Crossbill, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Redhead, Red-tailed Hawk, Ring-billed Gull, Ring-necked Duck, Ring-necked Pheasant, Rough-legged Hawk, Ruffed Grouse, Sharp-shinned Hawk, Snow Bunting, Snowy Owl, Song Sparrow, White-breasted Nuthatch, White-winged Crossbill, Wild Turkey. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. Species Maps. American Goldfinch, American Tree Sparrow, Black-capped Chickadee, Blue Jay, Bufflehead, Common Redpoll, Dark-eyed Junco, Purple Finch, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Ring-billed Gull, Snow Bunting. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Jennifer R. Foote, Daniel J. Mennill, Laurene M. Ratcliffe, and Susan M. Smith. Black-capped Chickadee. Poecile atricapillus. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Kimberly G. Smith, Keith A. Tarvin, and Glen E. Woolfenden. Blue Jay. Cyanocitta cristata. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Cameron K. Ghalambor and Thomas E. Martin. Red-breasted Nuthatch. Sitta canadensis. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Christopher T. Naugler, Peter Pyle, and Michael A. Patten. American Tree Sparrow. Spizelloides arborea. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Alan G. Knox and Peter E. Lowther. Common Redpoll. Acanthis flammea. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Gilles Gauthier. Bufflehead. Bucephala albeola. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Ingrid L. Pollet, Dave Shutler, John W. Chardine, and John P. Ryder. Ring-billed Gull. Larus delawarensis. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

J. Timothy Wootton. Purple Finch. Haemorhous purpureus. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

Kevin J. McGraw and Alex L. Middleton. American Goldfinch. Spinus tristis. Version 1.0 in Birds of the World. (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. Subscription Web Site. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Warren, Hamilton, Essex, Herkimer, Clinton, Franklin). Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton). Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Essex). Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. eBird. An Online Database of Bird Distribution and Abundance. Bird Observations (Hamilton, Essex). Retrieved 7 February 2023.

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III. Species Maps. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

Kevin J. McGowan and Kimberley Corwin (Eds). The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2008).

Alan E. Bessette, William K. Chapman, Warren S. Greene and Douglas R. Pens. Birds of the Adirondacks. A Field Guide (North Country Books, Inc., 1993).

John M.C. Peterson and Gary N. Lee. Adirondack Birding. 60 Great Places to Find Birds (Lost Pond Press, 2008).

Adirondack Park Agency. Checklist of Birds of the Adirondack Park Visitor Interpretive Center at Paul Smiths, NY. Undated.

Chris G. Earley. Sparrows & Finches of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (Firefly Books, 2003), pp. 18-19, 56-57, 64-67, 76-79, 82-95, 122-123. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

Arthur Cleveland Bent and Oliver L. Austin. Life Histories of North American Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, Towhees, Finches, Sparrows, and Allies. Part 1. Smithsonian Institution. United States National Museum. Bulletin 237, 1968). Retrieved 4 January 2022.

Arthur Cleveland Bent and Oliver Luther Austin. Life Histories of North American Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, Towhees, Finches, Sparrows, and Allies. Part 2. (Dover Publications, 1968). Retrieved 5 January 2022.

Arthur Cleveland Bent and Oliver Luther Austin. Life Histories of North American Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, Towhees, Finches, Sparrows, and Allies. Part 3. (Dover Publications, 1968). Retrieved 5 January 2022.

Tyler Hoar. Winter Finch Forecast 2020-2021. Finch Research Network. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

Tyler Hoar. Winter Finch Forecast 2021-2022. Finch Research Network. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

Tyler Hoar. Winter Finch Forecast 2022-2023. Finch Research Network. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

Joe Gyekis. Fall 2020 Superflight in Review: Pine Grosbeak, Evening Grosbeak, and Common Redpoll. Finch Research Network. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Late Fall and Early Winter Birding in the Champlain Valley! Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Early Spring Birding in the Champlain Valley. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Winter Birds of the Champlain Valley. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Counting Birds in the Champlain Valley. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Super March Birding in the Lake Champlain Region! Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Great Winter Birding in the Lake Champlain Region. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Brrrrding in the New Year! Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Ducks and Raptors along the Southern ADK Coast. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Great Ducks And Raptors Around Crown Point. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Raptors and Owls in the Lake Champlain Region! Retrieved 28 December 2021.

Alan Belford. Excellent Birding In The Lake Champlain Region! Retrieved 28 December 2021.